Technology has made huge breakthroughs over the past thirty-five years that I’ve been around criminal and forensic investigation (CSI). Without question, the next thirty-five are going to bring mind-blowing advances. I’ve looked into my forensic crystal ball to come up with five things I think will be real by 2050.

Technology has made huge breakthroughs over the past thirty-five years that I’ve been around criminal and forensic investigation (CSI). Without question, the next thirty-five are going to bring mind-blowing advances. I’ve looked into my forensic crystal ball to come up with five things I think will be real by 2050.

But first… let’s look at the top five since 1980.

1. Computers

When I started policing, the PC was unheard of.

The only computing system we had was a mammoth of a beast that filled-up many rooms at headquarters. CPIC, or the Canadian Police Information System, was in its infancy as was its American counterpart, NCIC or National Criminal Intelligence Center. Both systems are still around but, instead of having to phone to book appointments to use the system, the information now comes straight to the patrol cars or to a detective’s smart device.

The only computing system we had was a mammoth of a beast that filled-up many rooms at headquarters. CPIC, or the Canadian Police Information System, was in its infancy as was its American counterpart, NCIC or National Criminal Intelligence Center. Both systems are still around but, instead of having to phone to book appointments to use the system, the information now comes straight to the patrol cars or to a detective’s smart device.

Computers have affected every facet of forensic investigation.

Despite complex computerized analysis being fast and accurate, the routine is much easier. Report writing is far simpler – no more carbon paper to make multiple copies, no more white-out, and thank God for spell-check. Communications are instant with internet email and gone are the days of waiting for a report to show up in snail mail. Training is done through computerized simulation, sketching is replaced by computer-aided drawing, and administration is now done by the keyboard. Computers are what allowed the next four advances to occur.

2. AFIS – Automated Fingerprint Identification System

The science of fingerprinting has been around nearly one hundred and fifty years, but the mechanism of storage and matching prints was cumbersome. Known prints from criminals used to be rolled in ink and stored on paper and the latent prints from crime scenes were lifted in powder were stored in plastic sheets. There was no effective system to easily match the two. Today, suspect prints are digitally scanned and stored in data bases. Latent prints are still lifted in conventional manners, but they’re then scanned and put into a search engine where they can be matched right from the crime scene.

The science of fingerprinting has been around nearly one hundred and fifty years, but the mechanism of storage and matching prints was cumbersome. Known prints from criminals used to be rolled in ink and stored on paper and the latent prints from crime scenes were lifted in powder were stored in plastic sheets. There was no effective system to easily match the two. Today, suspect prints are digitally scanned and stored in data bases. Latent prints are still lifted in conventional manners, but they’re then scanned and put into a search engine where they can be matched right from the crime scene.

3. Photography

Today’s digital photography is a tremendous time-saver compared to the days of negative and image development. It’s instantaneous to share over the internet, even allowing an investigator to snap a digital photo in the field and email it to the other side of the world. Another facet of crime fighting is the incredible amount of mobile and stationary cameras that are out and about in society which capture movements of criminals before, during, and after events. Many crooks have gone down because they failed to realize they were on camera.

Today’s digital photography is a tremendous time-saver compared to the days of negative and image development. It’s instantaneous to share over the internet, even allowing an investigator to snap a digital photo in the field and email it to the other side of the world. Another facet of crime fighting is the incredible amount of mobile and stationary cameras that are out and about in society which capture movements of criminals before, during, and after events. Many crooks have gone down because they failed to realize they were on camera.

4. Education

Today’s forensic investigators are far better educated than in the 1980’s. Much of that is due to the ease of which information can be shared. Where it used to take great blocks of time and huge resources to assemble courses and conferences, many agencies now use webinars and on-line presence to create ‘virtual’ classrooms. Education and sharing information are the jewels in crime-fighting.

Today’s forensic investigators are far better educated than in the 1980’s. Much of that is due to the ease of which information can be shared. Where it used to take great blocks of time and huge resources to assemble courses and conferences, many agencies now use webinars and on-line presence to create ‘virtual’ classrooms. Education and sharing information are the jewels in crime-fighting.

5. DNA

Deoxyribonucleic acid or genetic fingerprinting is probably the best crime-fighting tool ever developed. Today, thanks to the computer, the sophistication and expediency of DNA testing has led to it being commonly – and accurately – used in the majority of serious crime investigations. Many convictions have been secured on DNA evidence alone. Conversely, many innocent people have been cleared of suspicion due to elimination by DNA typing.

Deoxyribonucleic acid or genetic fingerprinting is probably the best crime-fighting tool ever developed. Today, thanks to the computer, the sophistication and expediency of DNA testing has led to it being commonly – and accurately – used in the majority of serious crime investigations. Many convictions have been secured on DNA evidence alone. Conversely, many innocent people have been cleared of suspicion due to elimination by DNA typing.

So that’s what happened over the past third century. Ever wonder what’s going to happen over the next third?

Well, I’m gazing into the crystal ball and predict five things.

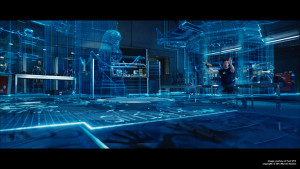

1. Holograms

3-D technology is commonplace in movies and on TV. Many criminal prosecutions are already presented through computer-aided reconstruction to lay out the scene, bullet paths, vehicle motions, and blood-spatter patterns.

3-D technology is commonplace in movies and on TV. Many criminal prosecutions are already presented through computer-aided reconstruction to lay out the scene, bullet paths, vehicle motions, and blood-spatter patterns.

I see a day when virtual-reality holograms are imaged in the middle of the courtroom so the jurors can watch a total recreation of how the crime went down.

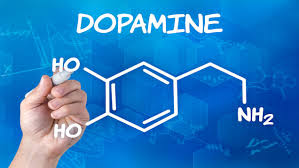

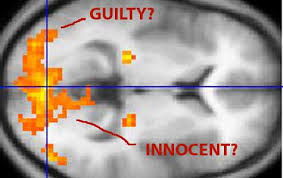

2. Brain-Scan Polygraphs

Conventional polygraphs have only slightly evolved in three decades and that was by the replacement of the old ink-needle charts with laptop technology. The basics of polygraphy still depends on the ability of a skilled operator to formulate key questions and then interpret the subject’s involuntary body reactions – pulse, respiration, blood pressure, galvanic skin responses, and perspiration.

Conventional polygraphs have only slightly evolved in three decades and that was by the replacement of the old ink-needle charts with laptop technology. The basics of polygraphy still depends on the ability of a skilled operator to formulate key questions and then interpret the subject’s involuntary body reactions – pulse, respiration, blood pressure, galvanic skin responses, and perspiration.

I see a day when brain mapping and analysis of how a subject responds under electroencephalography (EEG) and function magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) will replace the current polygraph. The technology is already here and research is underway towards its forensic application.

2. Laser Devices

I think lasers have phenomenal potential in forensics. Currently, laser lighting is used to amplify fingerprint and tool marking evidence. It’s also used in ballistic matching where the old electron-scanning comparison microscopes are being replaced by laser/laptop examiners like the Bullettrax 3D which makes the peaks and valleys of a ballistic engraving show up like satellite ground mapping radar images.

I think lasers have phenomenal potential in forensics. Currently, laser lighting is used to amplify fingerprint and tool marking evidence. It’s also used in ballistic matching where the old electron-scanning comparison microscopes are being replaced by laser/laptop examiners like the Bullettrax 3D which makes the peaks and valleys of a ballistic engraving show up like satellite ground mapping radar images.

I see a day when forensic investigators will map out a crime scene with hand-held laser devices to perfectly record information which will be transformed into hologram reproductions.

4. Ion-Sniffers

Detection of ions through gas chromatography mass spectrometers has been around fifty plus years and is still used daily in crime labs. What’s missing are portable devices to assist in field searches of buildings, vehicles, boats, planes, and the great outdoors. Often investigators know exactly what they’re looking for – a firearm, explosives, contraband, or even a dead body – but the parameters of the search area turn it into the needle-in-a-haystack scenario.

Detection of ions through gas chromatography mass spectrometers has been around fifty plus years and is still used daily in crime labs. What’s missing are portable devices to assist in field searches of buildings, vehicles, boats, planes, and the great outdoors. Often investigators know exactly what they’re looking for – a firearm, explosives, contraband, or even a dead body – but the parameters of the search area turn it into the needle-in-a-haystack scenario.

I see a day when the ionic signature of the article(s) being searched for are dialled into the device and it zooms right into the location.

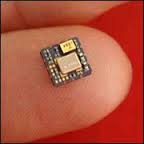

5. Satellite Tracking of Dangerous Criminals

Over the past few decades we’ve got a better handle on controlling violent and prolific offenders through DNA profile banks and ankle bracelets of parolees. We’ve also had tremendous advances in satellite technology where smart-bombs are delivered down terrorist’s chimneys and GPS aps tell you exactly where you are on the planet. We have microchips in everything from our bank cards to our pet Schnauzers and there are more cell phones in Africa than people. What we don’t know is where the dangerous .001 percent of the population are and have been.

Over the past few decades we’ve got a better handle on controlling violent and prolific offenders through DNA profile banks and ankle bracelets of parolees. We’ve also had tremendous advances in satellite technology where smart-bombs are delivered down terrorist’s chimneys and GPS aps tell you exactly where you are on the planet. We have microchips in everything from our bank cards to our pet Schnauzers and there are more cell phones in Africa than people. What we don’t know is where the dangerous .001 percent of the population are and have been.