Theodore (Ted) Kaczynski is a former math professor turned American domestic terrorist— the Unabomber—who’s serving life without parole for murdering three random people and injuring twenty-three others in a series of explosions. Kaczynski’s reign of terror lasted seventeen years from 1978 to 1995. During that time, the FBI conducted their lengthiest and most expensive investigation ever undertaken. The case is long closed, but a lingering question remains. Why’d he do it? What made the Unabomber tick?

Theodore (Ted) Kaczynski is a former math professor turned American domestic terrorist— the Unabomber—who’s serving life without parole for murdering three random people and injuring twenty-three others in a series of explosions. Kaczynski’s reign of terror lasted seventeen years from 1978 to 1995. During that time, the FBI conducted their lengthiest and most expensive investigation ever undertaken. The case is long closed, but a lingering question remains. Why’d he do it? What made the Unabomber tick?

Ted Kaczynski got his Unabomber tag long before he was caught. It developed through law enforcement and mainstream media because his victims were primarily associated with UNiversities and Airlines, hence UNA bomber. The name caught on and is still solely associated with Kaczynski today.

Before going into the Unabomber’s modus operandi, series of crimes, and how he was identified, it’s necessary to know who this man was. That’s the key to rationalizing his motive. It’s also necessary to know this man was not insane. No. Far from it. Actually, Kaczynski was a far-sighted genius.

Let’s look at what made the Unabomber tick.

Ted Kaczynski was born near Chicago in 1942 which makes him eighty today. His parents were working-class Polish Americans who provided a stable home for Ted and his younger brother, David. Early on, his family noticed a brilliance shining in Ted which also caught his teachers’ attention.

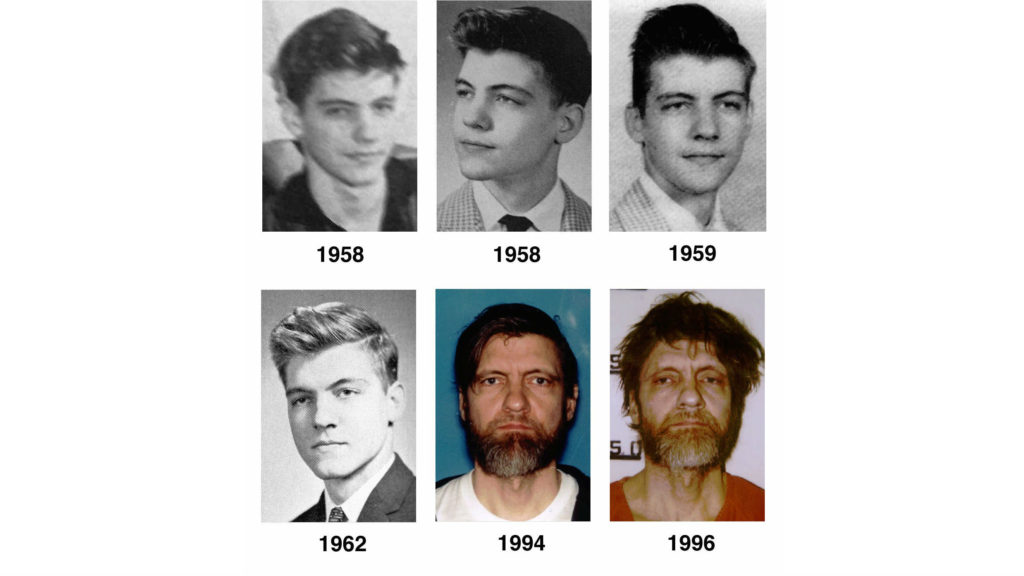

Academics came easy for Ted Kaczynski—especially mathematics. An early IQ test scored him at 167 which put Ted in the “highly gifted” category. He skipped grades in public school and entered Harvard University at age sixteen through a scholarship.

Academics came easy for Ted Kaczynski—especially mathematics. An early IQ test scored him at 167 which put Ted in the “highly gifted” category. He skipped grades in public school and entered Harvard University at age sixteen through a scholarship.

Peers and professors described Ted as “very intelligent but socially unprepared” for the campus. He was quiet, reserved, and not any source of trouble or rebelliousness. In 1962, at age twenty, Ted Kaczynski graduated with an advanced mathematics degree and a GPA of 4.12.

Ted Kaczynski went on to the University of Michigan where he earned his masters and doctorate in math. In 1967, his dissertation won the university’s top prize to which his doctoral adviser said it was the best he’d ever seen. It was so advanced, the advisor said, that perhaps only a dozen people in the country were equipped to understand it.

The University of California, Berkley, offered Ted Kaczynski a professor of mathematics role. He accepted it and, in 1968, he was given full tenure at Berkley. He was the youngest prof on the campus.

At this point in Ted Kaczynski’s life, his entire outlook changed. He became very disenchanted—disillusioned, embittered, or jaundiced, you could say—with “The System”. Without any explanation, he abruptly resigned on June 30, 1969, and moved back to his parent’s home.

Ted Kaczynski reconnected with his brother, David, and the two undertook a venture of building a 10-by-12-foot cabin in the secluded mountains near Lincoln, Montana. It was without power and water, but the isolation and discomfort suited Ted just fine. He lived off odd jobs and financial support from his family.

Ted Kaczynski reconnected with his brother, David, and the two undertook a venture of building a 10-by-12-foot cabin in the secluded mountains near Lincoln, Montana. It was without power and water, but the isolation and discomfort suited Ted just fine. He lived off odd jobs and financial support from his family.

The Unabombings began nine years after Ted Kaczynski quit his university position and seven years after he became a Montana hermit. Here is a bombing timeline copied from the FBI’s Unabomber website:

May 25, 1978: A passerby found a package, addressed and stamped, in a parking lot at the University of Illinois, Chicago Circle Campus. The package was returned to the person listed on the return address, Northwestern University Professor Buckley Crist, Jr. He did not recognize the package and called campus security. The package exploded upon opening and injured the security officer.

May 9, 1979: A graduate student at Northwestern University is injured when he opened a box that looked like a present. It had been left in a room used by graduate students.

November 15, 1979: American Airlines Flight 444 flying from Chicago to Washington, D.C., fills with smoke after a bomb detonates in the luggage compartment. The plane lands safely, since the bomb did not work as intended. Several passengers suffer from smoke inhalation.

June 10, 1980: United Airlines President Percy Woods is injured when he opened a package holding a bomb encased in a book called Ice Brothers by Sloan Wilson.

October 8, 1981: A bomb wrapped in brown paper and tied with string is discovered in the hallway of a building at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City. The bomb is safely detonated without causing injury.

May 5, 1982: A bomb sent to the head of the computer science department at Vanderbilt University injures his secretary, after she opened it in his office.

July 2, 1982: A package bomb left in the break room of Cory Hall at the University of California, Berkeley explodes and injures an engineering professor.

May 15, 1985: Another bomb in Cory Hall at the University of California, Berkeley injures an engineering student.

June 13, 1985: A suspicious package sent to Boeing Fabrication Division in Washington is safely detonated, but most of the forensic evidence was lost.

November 15, 1985: A University of Michigan psychology professor and his assistant are injured when they opened a package containing a three-ring binder that had a bomb. The bomber included a letter asking the professor to review a student’s master thesis.

December 11, 1985: A bomb left in the parking lot of a Sacramento computer store kills the store’s owner.

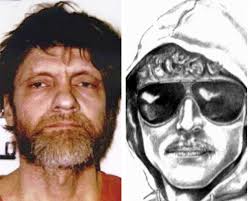

February 20, 1987: Another bomb left in the parking lot of a Salt Lake City computer store severely injures the son of the store’s owner. A store employee sees the man leave the bomb, and that witness account helped a sketch artist create the composite sketch.

June 22, 1993: A geneticist at the University of California is injured after opening a package that exploded in his kitchen.

June 24, 1993: A prominent computer scientist from Yale University lost several fingers to a mailed bomb.

December 19, 1994: An advertising executive is killed by a package bomb sent to his New Jersey home.

April 24, 1995: A mailed bomb kills the president of the California Forestry Association in his Sacramento office.

———

The FBI formed a task force in 1979. It was jointly with the US Postal Service and the ATF. The force grew to over 150 full-time investigators, lasted seventeen years, and amassed millions of documents .

To say the investigators were stumped is an understatement. They had no idea who the Unabomber was, but they knew one thing. They were dealing with a genius.

The Unabomber deliberately constructed his devices from common and untraceable components. Further, he chose his targets randomly. There was no clear pattern to his victims except that they were linked to various universities and airlines.

The big break in the Unabomber case came in 1995. An anonymous person, claiming to be the Unabomber, sent a 35,000-word essay to the FBI. It was titled Industrial Society and Its Future. This manifesto, as the Unabomber called it, came with a clause. The Unabomber promised to stop his campaign of terror if his views on the ills of modern society were published in the New York Times and the Washington Post.

The big break in the Unabomber case came in 1995. An anonymous person, claiming to be the Unabomber, sent a 35,000-word essay to the FBI. It was titled Industrial Society and Its Future. This manifesto, as the Unabomber called it, came with a clause. The Unabomber promised to stop his campaign of terror if his views on the ills of modern society were published in the New York Times and the Washington Post.

The FBI Director and the US Attorney General made a tough decision. Despite an existing policy never to negotiate with terrorists, they agreed that by asking the Times and the Post to print the Unabomber’s piece someone would recognize the author.

The manifesto became public on September 19, 1995. Someone did recognize the Unabomber’s style—his brother, David Kaczynski. David contacted the FBI and gave them the tip. Ted Kaczynski became Unabomber suspect #2,416.

On April 3, 1996, the FBI raided the Unabomber’s tiny Montana cabin and arrested Ted Kaczynski. They found mountains of indisputable evidence. So much so that Ted Kaczynski confessed and pleaded guilty to all charges. He was sentenced to life without parole on January 22, 1998.

On April 3, 1996, the FBI raided the Unabomber’s tiny Montana cabin and arrested Ted Kaczynski. They found mountains of indisputable evidence. So much so that Ted Kaczynski confessed and pleaded guilty to all charges. He was sentenced to life without parole on January 22, 1998.

Psychiatrists did extensive interviews with Ted Kaczynski. Primarily, this was to establish if his mind state was suitable to understand due process and stand trial or if he was clinically psychotic. The shrinks said, clearly, that Ted Kaczynski was in full control of his faculties—in fact, highly intelligent and completely aware of what he’d done.

Struggling to figure him out, they classified Ted Kaczynski in a Psychiatric Competency Report (as per the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, DSM 4) as:

Axis I: Schizophrenia, Paranoid Type, Episodic with Interepisode Residual Symptoms

Axis II: Paranoid Personality Disorder, with Avoidant and Antisocial Features

Nowhere in the 43-page report do they address a motive. That’s because they couldn’t find one. Neither could the courts, although motive is a non-necessary ingredient of establishing the burden of proof. Many armchair quarterbacks and internet sleuths have optioned opinions on why someone as bright as Ted Kaczynski would do something as crazy as Unibombing.

The answer is hiding in plain sight. Ted Kaczynski offers his motive up front in his 232-paragraph manifesto. Here are the opening quotes to help understand what made the Unabomber tick:

INDUSTRIAL SOCIETY AND ITS FUTURE

INTRODUCTION

The Industrial Revolution and its consequences have been a disaster for the human race. They have greatly increased the life-expectancy of those of us who live in “advanced” countries, but they have destabilized society, have made life unfulfilling, have subjected human beings to indignities, have led to widespread psychological suffering (in the Third World to physical suffering as well) and have inflicted severe damage on the natural world. The continued development of technology will worsen the situation. It will certainly subject human beings to greater indignities and inflict greater damage on the natural world, it will probably lead to greater social disruption and psychological suffering, and it may lead to increased physical suffering even in “advanced” countries.

The industrial-technological system may survive or it may break down. If it survives, it may eventually achieve a low level of physical and psychological suffering, but only after passing through a long and very painful period of adjustment and only at the cost of permanently reducing human beings and many other living organisms to engineered products and mere cogs in the social machine. Furthermore, if the system survives, the consequences will be inevitable: There is no way of reforming or modifying the system so as to prevent it from depriving people of dignity and autonomy.

If the system breaks down the consequences will still be very painful. But the bigger the system grows the more disastrous the results of its breakdown will be, so if it is to break down it had best break down sooner rather than later.

We therefore advocate a revolution against the industrial system. This revolution may or may not make use of violence; it may be sudden or it may be a relatively gradual process spanning a few decades. We can’t predict any of that. But we do outline in a very general way the measures that those who hate the industrial system should take in order to prepare the way for a revolution against that form of society. This is not to be a political revolution. Its object will be to overthrow not governments but the economic and technological basis of the present society.

In this article we give attention to only some of the negative developments that have grown out of the industrial-technological system. Other such developments we mention only briefly or ignore altogether. This does not mean that we regard these other developments as 2 unimportant. For practical reasons, we have to confine our discussion to areas that have received insufficient public attention or in which we have something new to say. For example, since there are well-developed environmental and wilderness movements, we have written very little about environmental degradation or the destruction of wild nature, even though we consider these to be highly important.

THE PSYCHOLOGY OF MODERN LEFTISM

Almost everyone will agree that we live in a deeply troubled society. One of the most widespread manifestations of the craziness of our world is leftism, so a discussion of the psychology of leftism can serve as an introduction to the discussion of the problems of modern society in general.

But what is leftism? During the first half of the 20th century leftism could have been practically identified with socialism. Today the movement is fragmented and it is not clear who can properly be called a leftist. When we speak of leftists in this article we have in mind mainly socialists, collectivists, “politically correct” types, feminists, gay and disability activists, animal rights activists and the like. But not everyone who is associated with one of these movements is a leftist. What we are trying to get at in discussing leftism is not so much movement or an ideology as a psychological type, or rather a collection of related types. Thus, what we mean by “leftism” will emerge more clearly in the course of our discussion of leftist psychology. (Also, see paragraphs 227-230.)

Even so, our conception of leftism will remain a good deal less clear than we would wish, but there doesn’t seem to be any remedy for this. All we are trying to do here is indicate in a rough and approximate way the two psychological tendencies that we believe are the main driving force of modern leftism. We by no means claim to be telling the whole truth about leftist psychology. Also, our discussion is meant to apply to modern leftism only. We leave open the question of the extent to which our discussion could be applied to the leftists of the 19th and early 20th centuries.

The two psychological tendencies that underlie modern leftism we call “feelings of inferiority” and “oversocialization”. Feelings of inferiority are characteristic of modern leftism as a whole, while oversocialization is characteristic only of a certain segment of modern leftism; but this segment is highly influential.

FEELINGS OF INFERIORITY

By “feelings of inferiority” we mean not only inferiority feelings in the strict sense but a whole spectrum of related traits; low self-esteem, feelings of powerlessness, depressive tendencies, defeatism, guilt, self-hatred, etc. We argue that modern leftists tend to have some such feelings (possibly more or less repressed) and that these feelings are decisive in determining the direction of modern leftism.

When someone interprets as derogatory almost anything that is said about him (or about groups with whom he identifies) we conclude that he has inferiority feelings or low self- 3 esteem. This tendency is pronounced among minority rights activists, whether or not they belong to the minority groups whose rights they defend. They are hypersensitive about the words used to designate minorities and about anything that is said concerning minorities. The terms “negro”, “oriental”, “handicapped” or “chick” for an African, an Asian, a disabled person or a woman originally had no derogatory connotation. “Broad” and “chick” were merely the feminine equivalents of “guy”, “dude” or “fellow”. The negative connotations have been attached to these terms by the activists themselves. Some animal rights activists have gone so far as to reject the word “pet” and insist on its replacement by “animal companion”. Leftish anthropologists go to great lengths to avoid saying anything about primitive peoples that could conceivably be interpreted as negative. They want to replace the word “primitive” by “nonliterate”. They seem almost paranoid about anything that might suggest that any primitive culture is inferior to our own. (We do not mean to imply that primitive cultures are inferior to ours. We merely point out the hyper sensitivity of leftish anthropologists.)

Those who are most sensitive about “politically incorrect” terminology are not the average black ghetto-dweller, Asian immigrant, abused woman or disabled person, but a minority of activists, many of whom do not even belong to any “oppressed” group but come from privileged strata of society. Political correctness has its stronghold among university professors, who have secure employment with comfortable salaries, and the majority of whom are heterosexual white males from middle- to upper-middle-class families.

Many leftists have an intense identification with the problems of groups that have an image of being weak (women), defeated (American Indians), repellent (homosexuals) or otherwise inferior. The leftists themselves feel that these groups are inferior. They would never admit to themselves that they have such feelings, but it is precisely because they do see these groups as inferior that they identify with their problems. (We do not mean to suggest that women, Indians, etc. are inferior; we are only making a point about leftist psychology.)

Feminists are desperately anxious to prove that women are as strong and as capable as men. Clearly they are nagged by a fear that women may not be as strong and as capable as men.

Leftists tend to hate anything that has an image of being strong, good and successful. They hate America, they hate Western civilization, they hate white males, they hate rationality. The reasons that leftists give for hating the West, etc. clearly do not correspond with their real motives. They say they hate the West because it is warlike, imperialistic, sexist, ethnocentric and so forth, but where these same faults appear in socialist countries or in primitive cultures, the leftist finds excuses for them, or at best he grudgingly admits that they exist; whereas he enthusiastically points out (and often greatly exaggerates) these faults where they appear in Western civilization. Thus it is clear that these faults are not the leftist’s real motive for hating America and the West. He hates America and the West because they are strong and successful.

Words like “self-confidence”, “self-reliance”, “initiative”, “enterprise”, “optimism”, etc., play little role in the liberal and leftist vocabulary. The leftist is anti-individualistic, procollectivist. He wants society to solve every one’s problems for them, satisfy everyone’s needs for them, take care of them. He is not the sort of person who has an inner sense of confidence in 4 his ability to solve his own problems and satisfy his own needs. The leftist is antagonistic to the concept of competition because, deep inside, he feels like a loser.

Art forms that appeal to modern leftish intellectuals tend to focus on sordidness, defeat and despair, or else they take an orgiastic tone, throwing off rational control as if there were no hope of accomplishing anything through rational calculation and all that was left was to immerse oneself in the sensations of the moment.

Modern leftish philosophers tend to dismiss reason, science, and objective reality, and to insist that everything is culturally relative. It is true that one can ask serious questions about the foundations of scientific knowledge and about how, if at all, the concept of objective reality can be defined. But it is obvious that modern leftish philosophers are not simply cool-headed logicians systematically analyzing the foundations of knowledge. They are deeply involved emotionally in their attack on truth and reality. They attack these concepts because of their own psychological needs. For one thing, their attack is an outlet for hostility, and, to the extent that it is successful, it satisfies the drive for power. More importantly, the leftist hates science and rationality because they classify certain beliefs as true (i.e., successful, superior) and other beliefs as false (i.e., failed, inferior). The leftist’s feelings of inferiority run so deep that he cannot tolerate any classification of some things as successful or superior and other things as failed or inferior. This also underlies the rejection by many leftists of the concept of mental illness and of the utility of IQ tests. Leftists are antagonistic to genetic explanations of human abilities or behavior because such explanations tend to make some persons appear superior or inferior to others. Leftists prefer to give society the credit or blame for an individual’s ability or lack of it. Thus if a person is “inferior” it is not his fault, but society’s, because he has not been brought up properly.

The leftist is not typically the kind of person whose feelings of inferiority make him a braggart, an egotist, a bully, a self-promoter, a ruthless competitor. This kind of person has not wholly lost faith in himself. He has a deficit in his sense of power and self-worth, but he can still conceive of himself as having the capacity to be strong, and his efforts to make himself strong produce his unpleasant behavior.1 But the leftist is too far gone for that. His feelings of inferiority are so ingrained that he cannot conceive of himself as individually strong and valuable. Hence the collectivism of the leftist. He can feel strong only as a member of a large organization or a mass movement with which he identifies himself.

Notice the masochistic tendency of leftist tactics. Leftists protest by lying down in front of vehicles, they intentionally provoke police or racists to abuse them, etc. These tactics may often be effective, but many leftists use them not as a means to an end but because they prefer masochistic tactics. Self-hatred is a leftist trait.

Leftists may claim that their activism is motivated by compassion or by moral principles, and moral principle does play a role for the leftist of the oversocialized type. But compassion and moral principle cannot be the main motives for leftist activism. Hostility is too prominent a component of leftist behavior; so is the drive for power. Moreover, much leftist behavior is not rationally calculated to be of benefit to the people whom the leftists claim to be trying to help. For example, if one believes that affirmative action is good for black people, does it make sense to demand affirmative action in hostile or dogmatic terms? Obviously it would be more productive 5 to take a diplomatic and conciliatory approach that would make at least verbal and symbolic concessions to white people who think that affirmative action discriminates against them. But leftist activists do not take such an approach because it would not satisfy their emotional needs. Helping black people is not their real goal. Instead, race problems serve as an excuse for them to express their own hostility and frustrated need for power. In doing so they actually harm black people, because the activists’ hostile attitude toward the white majority tends to intensify race hatred.

If our society had no social problems at all, the leftists would have to invent problems in order to provide themselves with an excuse for making a fuss.

We emphasize that the foregoing does not pretend to be an accurate description of everyone who might be considered a leftist. It is only a rough indication of a general tendency of leftism.

———

Theodore Kaczynski goes on for another 209 paragraphs but, by now, he’s made his point. He’s warning the world of the irresponsible and elite, progressive liberal movement—the Wokes—the counter & cancel culture we now see wrestling their own paranoid, non-acceptable of other viewpoints, Wokeism chokehold on political and academic power—meaning their ideologic, counter-right, non-common-sense agendas. Ted Kaczynski saw this in 1995, but he had no platform like today’s social media he’d had to get out his message. His only venue was through mainstream publications like the New York Times and the Washington Post.

Theodore Kaczynski goes on for another 209 paragraphs but, by now, he’s made his point. He’s warning the world of the irresponsible and elite, progressive liberal movement—the Wokes—the counter & cancel culture we now see wrestling their own paranoid, non-acceptable of other viewpoints, Wokeism chokehold on political and academic power—meaning their ideologic, counter-right, non-common-sense agendas. Ted Kaczynski saw this in 1995, but he had no platform like today’s social media he’d had to get out his message. His only venue was through mainstream publications like the New York Times and the Washington Post.

By setting himself up with the notoriety he created through the Unabomber persona, Theodore (Ted) Kaczynski achieved his goal and his manifesto lives on forever, easily obtained through the internet.

That’s what made the Unabomber tick.