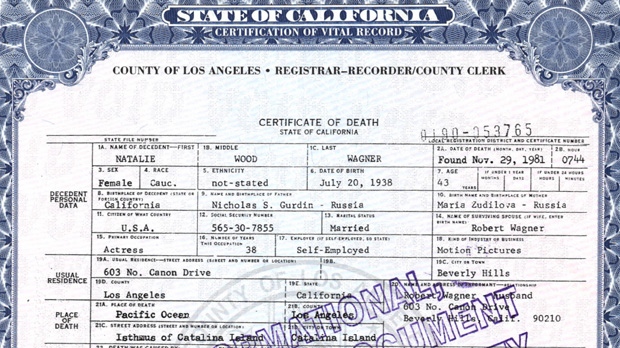

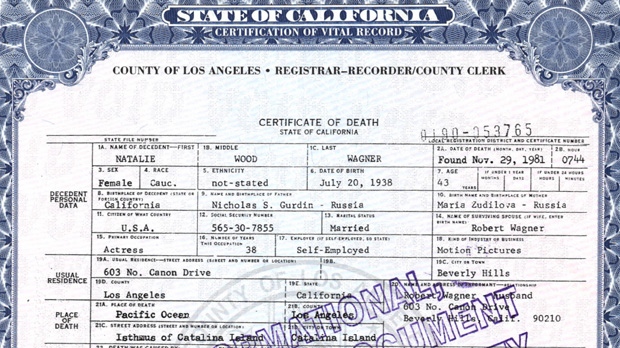

As Hollywood mysteries go, Natalie Wood’s suspicious death tops the list. On November 29, 1981, the 43-year-old movie superstar was found floating off Santa Catalina Island, 25 miles southwest of Long Beach, California. The Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department and Coroner’s Office quickly concluded Wood died from an accidental drowning. But that’s no longer the case. Today, Natalie Wood’s manner of death is officially ruled a “drowning from undetermined factors”. Now her then-husband, actor Robert Wagner, is officially a police “person of interest” for causing Wood’s death.

As Hollywood mysteries go, Natalie Wood’s suspicious death tops the list. On November 29, 1981, the 43-year-old movie superstar was found floating off Santa Catalina Island, 25 miles southwest of Long Beach, California. The Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department and Coroner’s Office quickly concluded Wood died from an accidental drowning. But that’s no longer the case. Today, Natalie Wood’s manner of death is officially ruled a “drowning from undetermined factors”. Now her then-husband, actor Robert Wagner, is officially a police “person of interest” for causing Wood’s death.

The question of what really happened in Natalie Wood’s death has never been answered. It’s never disappeared from public interest and that’s for good reason. At the time, Wood was one of Hollywood’s hottest stars. So was Robert Wagner. Together, the pair was a celebrity sensation—a mix of love, hate, beauty, sex, scandal, jealousy and violence. No wonder there’s still a fascination in this unsolved case after nearly four decades.

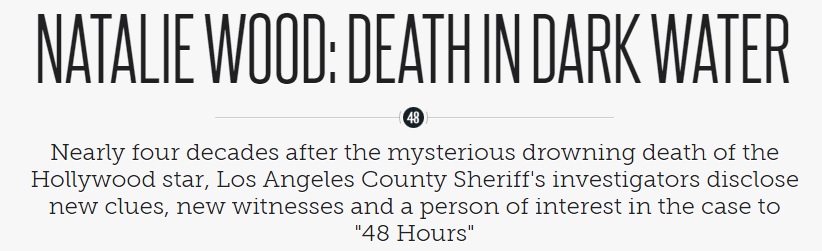

That Natalie Wood died by drowning is indisputable. That’s crystal clear. But, how she ended up in the water is murky as hell. The circumstances stink like an old, rotten fish and the balance of probabilities says Wagner threw Natalie in after a night’s drunken fight. This is what the LA sheriff detectives also think. They recently did an hour-long episode on CBS 48 Hours called Natalie Wood—Death in Dark Water to rock the boat and surface new evidence.

Likely, here’s what really happened in Natalie Wood’s death.

The Wood—Wagner Relationship

Natalie Wood was a true child acting prodigy. She was born Natalia Zakharenko in San Francisco to Russian and Ukrainian immigrant parents. Wood’s first role was at age 4. By 8, she co-starred in the 1947 Christmas Classic Miracle on 34th Street, and at sixteen she was nominated for an Oscar alongside James Dean in Rebel Without a Cause. 2 more Academy Award nominations followed for Splendor in the Grass and Love With the Proper Stranger. Other successes included West Side Story and Gypsy. By 25, Wood’s natural beauty and acting talent were in high demand.

Robert Wagner claimed most of his success and fame in television roles. Wagner was the handsome leading man in the 70s and 80s shows It Takes a Thief, Switch and Hart to Hart. However, he had many A and B-list movie roles pre and post-TV. Wagner is now 88 and lives in Aspen, Colorado with actor wife, Jill St. John.

Wood admitted to having a childhood crush on Robert Wagner who was eight years senior. They married in 1957 when she was 19 and he was 27. That ended in a 1962 divorce with Wood suing Wagner for “mental cruelties”. They remarried in 1973 and were still legally attached when Wood died. That union was again shaky. Wood was rumored to be having an affair with actor Christopher Walken during their relationship filming the movie Brainstorm.

Thanksgiving Weekend, 1981

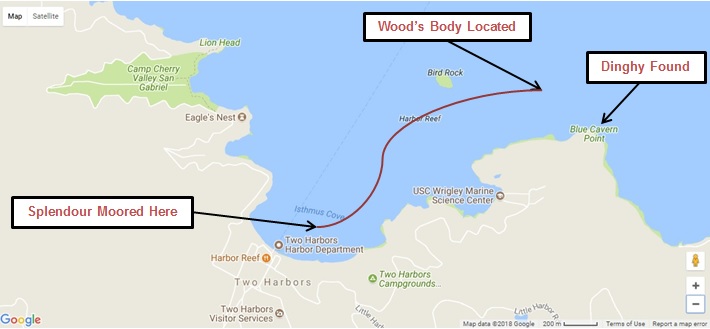

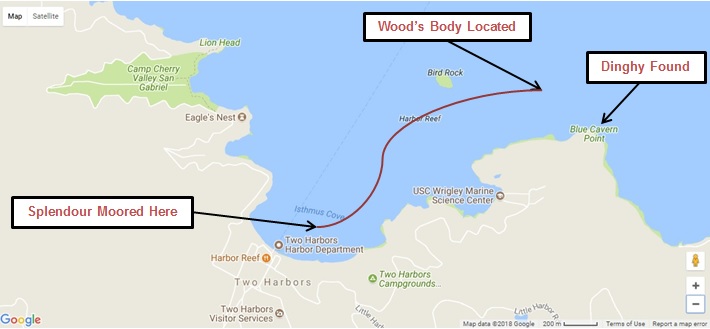

Wood and Wagner planned to spend the 1981 Thanksgiving weekend on their 60-foot motor yacht Splendour moored at Two Harbors on Santa Catalina Island. Catalina lies 25 miles off the California coast between Los Angeles and San Diego. The harbor sits at the Isthmus of Catalina where this popular southern California boating spot narrows. Being on the east side of Catalina, the Two Harbors moorage is protected from the open Pacific Ocean.

It’s not clear why and when, but Wood invited her Brainstorm co-star, Christopher Walken, to join them on the yacht for the weekend. That didn’t go over well with Wagner. He’d already suspected intimacy between his wife and Walken. A few weeks earlier, Wagner flew to the South Carolina Brainstorm film site to check on them. Also accompanying this triangle to Catalina Island was Wagner’s boat captain, Dennis Davern, who also served as Wagner’s caretaker.

The foursome arrived at Two Harbors on Friday afternoon, November 27. The weather was cool, rainy and windy. Davern tied the Splendour to moorage buoy N1 at the center of Isthmus Cove, then detached the yacht’s 13-foot Zodiac inflatable dinghy named Valliant. At about 4 pm, Wood, Wagner, Walken and Davern rode the dinghy from the moored yacht and tied up at the Two Harbors main wharf. They hiked a short distance to a bar/restaurant called Doug’s Harbor Reef, sat down, and began drinking.

Witnesses, including the bar manager Don Whiting, later reported the group seemed in good spirits, and there was no sign of tension. Wood and Walken appeared to be flirting, but Wagner didn’t appear upset. About 10 pm, the four left the bar and took the Valliant dinghy back to the Splendour. There, things got tense. Wood and Wagner began to argue—apparently over how she was reacting to Walken’s attention and Walken’s views about Wood’s acting career—but there was no sign of violence.

Witnesses, including the bar manager Don Whiting, later reported the group seemed in good spirits, and there was no sign of tension. Wood and Walken appeared to be flirting, but Wagner didn’t appear upset. About 10 pm, the four left the bar and took the Valliant dinghy back to the Splendour. There, things got tense. Wood and Wagner began to argue—apparently over how she was reacting to Walken’s attention and Walken’s views about Wood’s acting career—but there was no sign of violence.

Wood stated she had enough from Wagner and asked boat skipper Davern to take her ashore in the dinghy. It was around midnight when Wood checked into a motel room and paid for a separate one for Davern. The next morning, Saturday, November 28, Davern drove Wood back to the yacht where she and Wagner acted as if nothing had happened. Wood made breakfast for the group and everyone appeared pleasant.

At approximately 3 pm on Saturday afternoon, Davern drove Wood and Walken ashore in the dinghy. Wagner stayed on the Splendour attending to personal matters. Davern returned to the yacht, then skippered Wagner ashore about 4:30 where they joined Wood and Walken in the Harbor Reef. Wood and Walken were already into the champagne and carried on, seeming to ignore Wagner and Davern. The four ordered dinner around 8:00 pm and stayed until between 10 and 10:30. Again, all appeared on good terms while inside the bar.

They left as an intoxicated group. Their drunken condition was significant enough for manager Whiting to call Harbor Patrol guard Kurt Craig asking to keep a watch for his departing guests, making sure they got safely back on their yacht, which they did. What happened next is unknown. Somehow, Wood ended up dead—her seriously bruised body face-down in the water. Over the years, the three male survivors have made elusive, inconsistent and changing statements.

Finding Natalie Wood’s Body

Robert Wagner made a marine radio call reporting a missing person at 1:30 am on Sunday, November 29. Don Whiting, who lived on a nearby boat, heard the call. He noted the time. Soon, a search began including Whiting, the Harbor Patrol, the Coast Guard and the Los Angeles Sheriff’s Department. Weather conditions were rainy, cool and windy. Search efforts were hampered by darkness with no moon or star light.

At first light, a Sheriff’s helicopter joined the search. Airborne observers quickly spotted a bright red object floating approximately 1mile north-east of where the Splendour was moored. It was approximately 200 yards off a land tip called Blue Cavern Point. At 7:44 am, a surface vessel reached the object and confirmed it was Natalie Wood, deceased.

Wood was in a suspended position with her face in the water, arms outstretched and long hair floating on the surface. Her torso, legs and feet were downward. The only thing keeping her from sinking was her red down jacket which acted as a buoyancy compensator or flotation device. Aside from the jacket, Wood was only dressed in a blue and red flannel nightgown and calf-length, blue argyle socks. She had no shoes or underclothes.

Searchers pulled Wood from the water and placed her on a “Stokes-Litter” search & rescue basket. Her body was transported to a Harbor Patrol shelter and placed in a hyperbolic chamber used for decompressing divers. She was held for safe-keeping while an investigator from the LA County Coroner Office arrived to transport the body back to the mainland for an autopsy.

The missing dinghy Valliant was also found near to where Wood’s body was located. It was resting against the shore at Blue Cavern Point. An examination found the Zodiac’s outboard motor lowered in the water, the control in neutral, the key in the “off” position and the oars fastened down. It appeared never used.

The Preliminary Investigation

Pam Eaker from the LA Coroner’s Office and Detective Duane Razier from the LA County Sheriff’s Department were the preliminary investigators in Natalie Wood’s death. Eaker was an experienced death investigator as was Razier. They only made a brief examination of Wood’s body by examining rigor mortis and photographing it for identification. They noted some bruising to Wood’s left knee but couldn’t see much of her skin due to being covered by the high socks and knee-length nightgown. Wood was lying face up and they didn’t examine her posterior. They also noted foam coming from Wood’s mouth which is typical in drownings.

Eaker’s report indicates when searchers pulled Wood from the water, rigor mortis was minimal. However, when Eaker did a cursory exam at 1:00 pm, Wood was in nearly full rigor. These investigators recorded equilibrium air and water surface temperatures of 62 degrees Fahrenheit and Wood’s internal temperature at 65° F. Eaker’s field investigation report is publicly available but not the police report. It’s unclear if any formal statements were taken at this time.

Eaker’s report indicates when searchers pulled Wood from the water, rigor mortis was minimal. However, when Eaker did a cursory exam at 1:00 pm, Wood was in nearly full rigor. These investigators recorded equilibrium air and water surface temperatures of 62 degrees Fahrenheit and Wood’s internal temperature at 65° F. Eaker’s field investigation report is publicly available but not the police report. It’s unclear if any formal statements were taken at this time.

Eaker reports she spoke to Robert Wagner who stated he last remembered seeing his wife at 11:45 pm. When Wagner realized Wood was missing, he made a radio call for help. Eaker’s report does not record what time Wagner claims he found Wood missing. The report defers to Don Whiting who she interviewed. He was clear the radio call occurred at 1:30 am as he noted the time.

Whiting also provided information about the Wagner/Wood party being intoxicated when they left the bar between 10 and 10:30 pm. He expressed concern for their welfare on the water due to obvious drunkenness, but he made no claim there was tension among the group. It appears Whiting was the only independent witness interviewed. It makes no reference to other occupants onboard the Splendour and appears Davern and Walken were not formally interviewed.

The only reference to Dennis Davern is that he identified Natalie Wood’s body. Robert Wagner did not view his wife’s body at Catalina Island. Rather, he flew back to Los Angeles with Walken on board a sheriff’s helicopter, leaving Davern to deal with the Splendour.

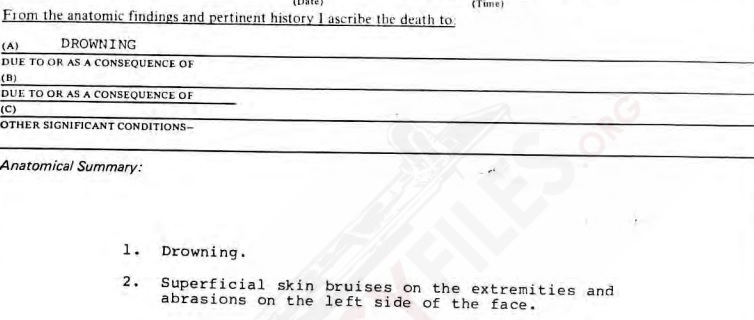

Natalie Wood’s Autopsy

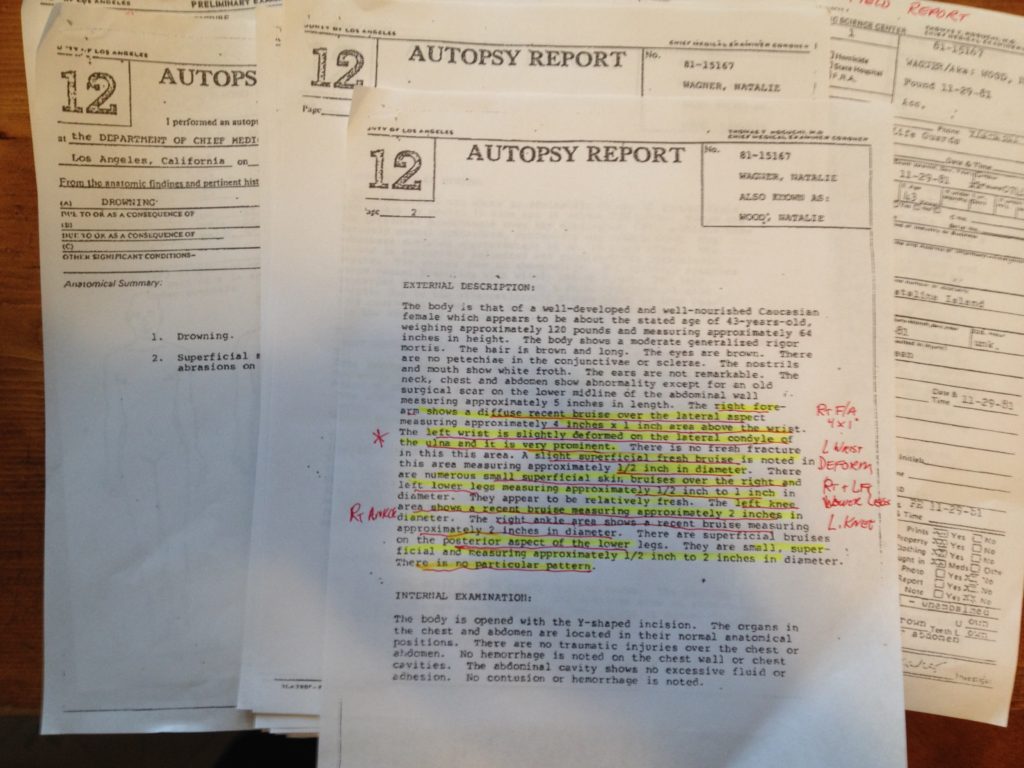

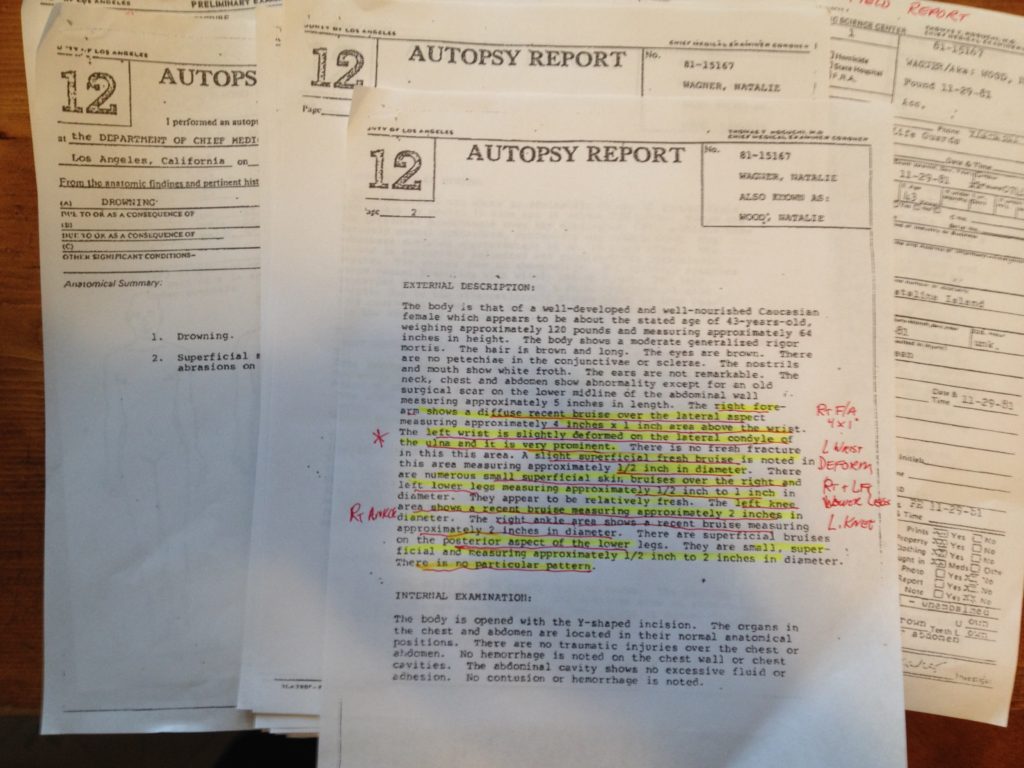

Natalie Wood’s autopsy started at 1:30 pm on Monday, November 30th in the LA County morgue. Dr. Joseph Choi, Deputy Medical Examiner, did the postmortem exam which was overseen by Chief Medical Examiner, Dr. Thomas Noguchi. Noguchi was a high-profile medical examiner well-known as the “coroner to the stars” for work on celebrities like Marilyn Monroe, Bobby Kennedy, John Belushi, Sharon Tate and Janis Joplin to name a few. Noguchi has also been well-criticized for seeking fame over fact in his pathology career.

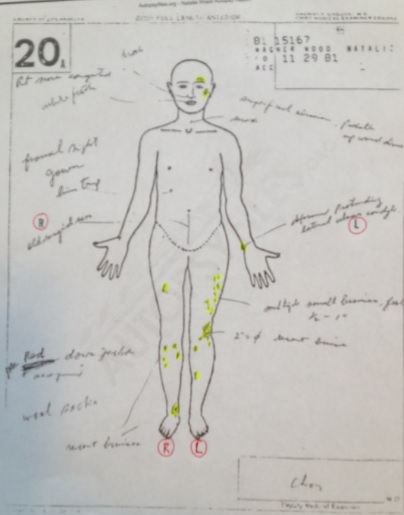

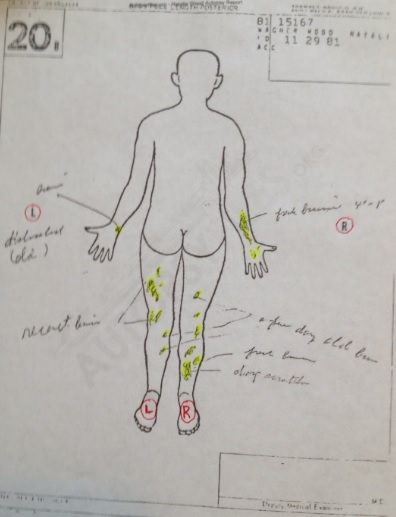

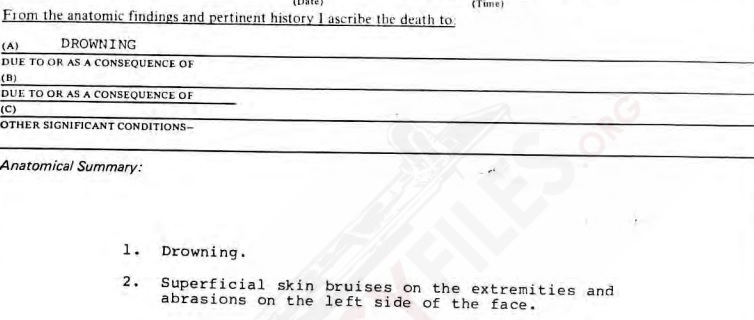

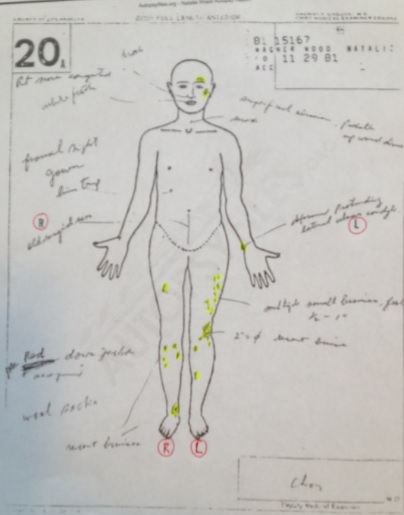

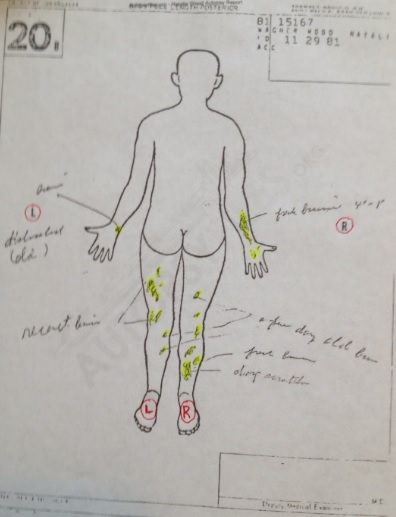

The autopsy report and follow-up toxicology report are well-detailed and publically published. Autopsies follow a regular procedure starting with external observations and full-body X-rays. Wood had no broken bones, fractures or head trauma. However, her arms and legs were a mass of bruises as well as notable abrasions on her left cheek and above her left brow. These were superficial contusions rather than lacerations and entirely consistent with mechanical or manual pressure application. They were also antemortem injuries and occurred before death.

Natalie Wood’s internal examination showed a healthy, early-middle-aged woman. There were no natural disease processes evident—nothing natural to cause a medical event which led to her accidentally falling in the water while unconscious. Her lungs were heavy with seawater, and her airway was obstructed with foamy froth. Clearly, Wood’s medical cause of death was due to drowning. However, that did not explain how she got in the water. Nor did it account for her considerable bruising. These are the surface trauma injuries noted Wood’s autopsy report:

- Superficial abrasion and contusion on left cheek and forehead in upward motion.

- Diffused bruise over lateral aspect of right forearm measuring 4” x 1” above the wrist.

- Prominent deformity of left wrist on lateral condyle of the ulna bone.

- Superficial bruise in deformity approximately ½” diameter.

- Numerous bruises over right and left lower legs ranging from ½” to 1” in diameter.

- Significant bruise to anterior of left knee measuring 2” in diameter.

- Bruising to right ankle area measuring 2” in diameter.

- Many smaller superficial bruises to anterior and posterior lower legs and thighs measuring approximately ½” to 2” in diameter with no particular pattern.

Photos of Wood’s bruising don’t appear available on the internet like some celebrity death images are. However, Wood’s autopsy anterior and posterior sketches, or face sheets as they’re called, are attached to the autopsy report. They indicate over 50 separate bruise markings.

There’s a significant note in the autopsy report that skin sections of the significant bruises were removed from Wood’s body. These were microscopically examined from histopathological slides and confirmed to be subcutaneous hemorrhages that can only occur while the subject was alive. They were also “very fresh”, indicating they occurred immediately before Wood’s heart stopped by drowning. These injuries were not the result of earlier trauma that was healing.

Additional in Wood’s autopsy report is mention of her estimated time of death. Dr. Choi’s conclusion reads:

“The autopsy findings are consistent with drowning in the ocean. The time of death is difficult to pinpoint, but it appears to be about midnight on November 28/29, 1981. Most of the bruises on the body are superficial and probably sustained at the time of drowning.”

Choi based his estimated time of death based on three factors. One is that approximately 500 ccs of undigested food remained in Wood’s stomach. Based on the witness evidence that she’d eaten around 9:00 pm, that digestive sequence is consistent with a 3-hour period before her digestive system stopped. Second, the water temperature and Wood’s physical size (120 pounds) would have quickly brought on hypothermia. Third, the rigor state was consistent with death occurring about 8 hours before her body was found.

Choi based his estimated time of death based on three factors. One is that approximately 500 ccs of undigested food remained in Wood’s stomach. Based on the witness evidence that she’d eaten around 9:00 pm, that digestive sequence is consistent with a 3-hour period before her digestive system stopped. Second, the water temperature and Wood’s physical size (120 pounds) would have quickly brought on hypothermia. Third, the rigor state was consistent with death occurring about 8 hours before her body was found.

Rigor mortis is mostly dependent on ambient temperature and body size. Generally, the warmer and heavier a body is—the faster rigor sets. Wood was small and died in a cold environment. It’s expected her rigor process would be delayed while suspended in chilled water. It’s also expected rigor would rapidly fix once removed from cold water and placed in a warmer hyperbolic chamber.

Despite questionable bruising, the Los Angeles County Coroner concluded that Wood accidentally drown while intoxicated and falling into the ocean as she tried moving the dinghy. Wood’s blood-alcohol content was 0.14% which is significant for a slight person. There was no sign of illicit intoxicants like cocaine or opiates. She was simply high on alcohol which may have contributed to an early expiration in the water.

In mid-December, 1981, the LA County Coroner Office released its findings. Natalie Wood officially drowned after some mishap with the dinghy. They attributed her extensive bruising to the struggle with a rubber boat. No foul play occurred, they said, and the Sheriff’s Department agreed. Natalie Wood’s death was declared accidental, and the case was closed.

Dennis Davern’s Confession

That conclusion never sat well with the media and the public. For years, speculation and rumors swirled that there was more to Wood’s death than officially concluded. The conclusion never sat well with two other people. One was Natalie Wood’s sister, Lana Wood. The other was Dennis Davern. Together, they petitioned the coroner and police in 2012 to reopen the case. The triggering factor was Daven confessing to police that he’d lied during the 1981investigation. He claimed his conscience finally got to him.

Davern stated he’d been coerced by Wagner to keep quiet. At the time, Wagner was Davern’s boss and sole meal ticket. According to Davern’s new statement, there’d been tension for two days between Wagner and Wood, and it was jealousy over Chris Walken. Davern stated when they got back to the Splendour on the Saturday night, Wood and Walken were very cozy. Finally, Wagner snapped. He grabbed a wine bottle and smashed it, yelling at Walken, “Jesus Christ! What are you trying to do? Fuck my wife?”

Davern stated he’d been coerced by Wagner to keep quiet. At the time, Wagner was Davern’s boss and sole meal ticket. According to Davern’s new statement, there’d been tension for two days between Wagner and Wood, and it was jealousy over Chris Walken. Davern stated when they got back to the Splendour on the Saturday night, Wood and Walken were very cozy. Finally, Wagner snapped. He grabbed a wine bottle and smashed it, yelling at Walken, “Jesus Christ! What are you trying to do? Fuck my wife?”

Wood was drunk and flipped out. It became a screaming match but there was no physical violence yet. Wood stormed off, saying she was going to bed. She went below to her stateroom, changing into her bedclothes. Walken slipped to his room in a forward cabin while Davern quietly went up to the bridge. Davern places the time as just before midnight.

Within a few minutes, Davern claims he heard Wagner and Wood fighting again. This time, there was physical violence as he could hear banging, crashing and thumping. Then the pair went out on the open stern deck where the dinghy was tied up, floating astern. Davern claimed more physical fighting took place, and he heard Wagner scream at Wood, “Get off my fucking boat!” More fighting took place and, suddenly, everything went quiet.

Davern is clear he did not hear a “sploosh” or Wood splashing or crying for help in the water. He claims he waited a few more minutes, then went down and found Wagner alone in the salon. Davern states Wagner appeared distraught, nervous, sweaty and shaking. He told Davern that Wood “was gone”. Wagner’s story was she took the dinghy and went to shore like she did the previous night.

Davern is clear he did not hear a “sploosh” or Wood splashing or crying for help in the water. He claims he waited a few more minutes, then went down and found Wagner alone in the salon. Davern states Wagner appeared distraught, nervous, sweaty and shaking. He told Davern that Wood “was gone”. Wagner’s story was she took the dinghy and went to shore like she did the previous night.

Davern didn’t buy it for a minute. For one thing, he never heard the dinghy’s noisy outboard engine start. For another, Davern knew Wood didn’t know how to operate it. As well, he knew she wouldn’t go out alone in dark, stormy conditions. If she truly wanted to leave, she’d have asked Davern to drive her as before. And, Davern knew Wood was terrified of dark sea water.

Davern claims he wanted to start an immediate search. Wagner refused, saying they’d wait for a bit and see if she’ll return. Wagner broke open a bottle of scotch and shared it with Davern over the next hour and a half. Despite Davern’s pleadings to start a search, Wagner refused. Finally, at 1:30 am, Wagner placed the first radio call. During this time, there was no contact with Chris Walken. Apparently, he stayed in his room till morning.

Davern makes another astounding claim. He states after Wood’s body was found, but before investigators arrived, Wagner had a closed-door meeting with Davern and Walken. Davern alleges Wagner laid out a common story they were all to stick with. Daven doesn’t allege Wagner admitting throwing Wood in the water. Rather, the story he wanted them to relay is no one saw her leave and there was no fight. Daven states Wagner ended the session with, “That’s the story. Okay? Everyone got it?”

Davern makes another astounding claim. He states after Wood’s body was found, but before investigators arrived, Wagner had a closed-door meeting with Davern and Walken. Davern alleges Wagner laid out a common story they were all to stick with. Daven doesn’t allege Wagner admitting throwing Wood in the water. Rather, the story he wanted them to relay is no one saw her leave and there was no fight. Daven states Wagner ended the session with, “That’s the story. Okay? Everyone got it?”

Natalie Wood’s Death Case is Reopened

Based on Dennis Davern’s information, the Los Angeles Sheriff’s Department reopened Natalie Wood’s death investigation in May 2012. They held a joint meeting with the current Chief Medical Examiner who reviewed the medical evidence. Dr. Choi was now dead and Dr. Nagouchi was long retired. This review concluded Wood’s cause of death was still from drowning. However, they gave the opinion that Wood’s bruises were far more consistent with a multi-person fight onboard the yacht rather than a sole struggle in the water.

The LA County Coroner amended Wood’s death certificate from an accidental drowning to “Drowning and Other Undermined Factors”. They stopped short of ruling it a homicide which requires proof the death was caused by another human being. However, they could no longer support an accidental conclusion.

The new investigators with the LA Sheriff’s Department also stop short of claiming foul play. They describe their investigation as being a suspicious death where the full truth has not been revealed. They are also tactful about calling Robert Wagner as a murder suspect. They classify him as a person of interest who they’d like to interview.

Lieutenant John Corina and Detective Sergeant Ralph Hernandez state they’ve made ten attempts to interview Wagner. Each time, he’s refused. Now, they’re appealing to the public for any information pertinent to the Natalie Wood case. Corina and Hernandez gave a candid look at their investigation during the CBS 48 Hours documentary aired February 5th, 2018. They claim to have new witnesses come forward corroborating Davern’s claim of a fight on the Splendour’s back deck. Conclusively, they say, it was Robert Wagner and Natalie Wood.

No one, however, states they actually saw Wood go into the water. As Lt. Corina puts it, “She got in the water somehow, and I don’t think she got in the water by herself”. Corina adds, “This doesn’t meet the smell test. Wagner’s version makes absolutely no sense. We’d love to hear his side, his truthful version of the events. What he’s told original investigators and what he’s portrayed since then really don’t add up to what we’ve found.”

No one, however, states they actually saw Wood go into the water. As Lt. Corina puts it, “She got in the water somehow, and I don’t think she got in the water by herself”. Corina adds, “This doesn’t meet the smell test. Wagner’s version makes absolutely no sense. We’d love to hear his side, his truthful version of the events. What he’s told original investigators and what he’s portrayed since then really don’t add up to what we’ve found.”

Det. Sgt. Hernandez states, “She (Wood) looked like the victim of an assault.” Corina goes further, saying, “She’s seriously bruised on the arms, legs and face. Then she goes to get in the dinghy and into town—in her pajamas, socks, in the middle of the night. It’s raining out and midnight when she can’t see, but she’s going to take the dinghy, which she never drives, probably doesn’t know how to drive, and take it to town. That makes no sense at all.”

Corina and Hernandez discuss their witness evidence credibility. They rate their two independent witnesses as “very credible” and call Davern “credible” based that he originally misled investigators but now his new version is corroborated or backed up by the independent people. As for what Christopher Walken has said, Corina states, “He’s cooperating, but we’ve agreed to keep his information confidential. For now.”

When asked if they’ll ever solve the Natalie Wood case, Corina answered, “We’re closer to understanding what happened, but critical questions remain. Time is our biggest enemy here with over 36 years passing since it happened. We’re reaching out one last time to see if anyone will come forward with information they may know.”

How Natalie Wood Likely Went in the Water

To think Natalie Wood went in the water voluntarily is preposterous. She never went for a relaxing swim. She was not suicidal by any stretch of the imagination. And it’s highly unlikely she was trying to stealthily flee by untying the dinghy and slipping into a guideless tender. It’s even crazier to think a movie star headed for some free fun on a small town at midnight, soaking wet in pitch black with no shoes and no underwear.

No. There’s only one explanation. Someone dragged Natalie Wood off that boat into the water—kicking and screaming. That was her husband, Robert Wagner. Nothing else makes sense.

No. There’s only one explanation. Someone dragged Natalie Wood off that boat into the water—kicking and screaming. That was her husband, Robert Wagner. Nothing else makes sense.

The key to understanding what physically took place is examining Wood’s bruise pattern recorded at her autopsy. These are in no way consistent with thrashing about in the water while trying to climb into a flexible dingy. Natalie Wood’s bruises are entirely consistent with being gripped by her wrists and around her legs and arms. Her face abrasion is consistent with being dragged face-down, backward, along the yacht’s rear deck. Nothing else fits.

What’s really telling is the damage to the outside of Natalie Wood’s left wrist. By stating there’s a very prominent deformity to the lateral condyle of the ulna with no fresh fracture means her wrist was dislocated but not broken. That requires a lot of force—a painful force—an external force. *Note – there is some indication through comments sent to me that Natalie Wood may have had this deformity to her left wrist for some time before her death however the autopsy report reads that this was a dislocation which would have been painful if not treated and reset.*

All evidence—physical, medical and witness observations—indicates Wood and Wagner were in an intense fight. That alleged statement, “Get off my fucking boat!” is something a witness just doesn’t make up. That statement has to be truthful. The “my boat” phrase sums their relationship, and Wagner was making sure “his” property was going off “his boat” one way or another.

At the end, Wood was prone on the deck, holding on to something for dear life. Wagner was gripping her legs and thighs, trying to free her. He ripped her wrists, possibly dislocating one. Then, Robert Wagner wrestled Natalie Wood by the legs, thighs and whatever lower extremities he could to shove his wife to her death in dark sea water.

The Problem with Homicide Charges

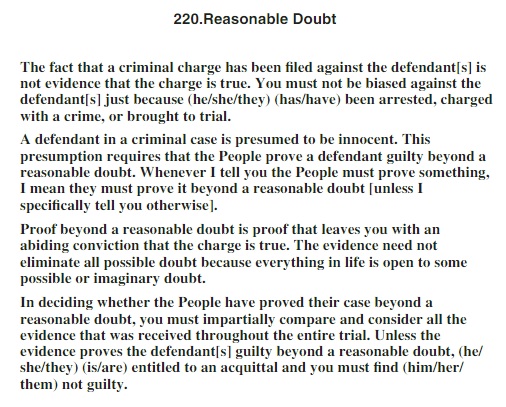

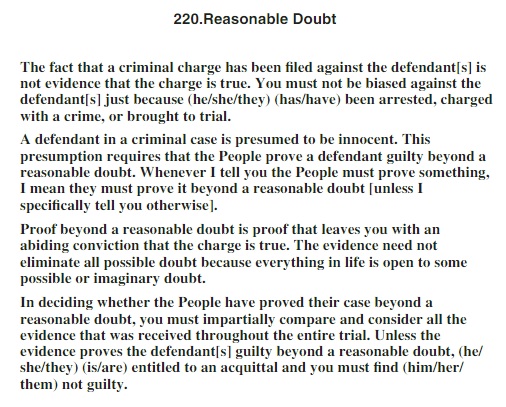

On the surface, it definitely seems Robert Wagner is hiding what really happened in Natalie Wood’s death. You’d think if Wagner was clean, he’d scream for an inquest to find what happened to his love, never mind clear his name of suspicion. But he’s keeping quiet. That’s understandable, given that—if dirty—he’d spend years in jail even if convicted of manslaughter rather than first or second-degree murder. However, reasonable suspicion based on a balance of probabilities is a lesser test than the state proving an accused’s guilt beyond a reasonable doubt. Here’s the wording from the California Penal Code on the directions a judge must read to the jury regarding reasonable doubt.

Given the evident factors of intoxication and relative spontaneity, it’s hard to argue Wagner planned and intended to kill Wood. It’d be a tough row to hoe proving he clearly meant for her to drown as required for a second-degree conviction. Manslaughter is the best homicide ruling the prosecution could hope for in this situation.

But there’s no smoking gun in the Wood/Wagner case. That’d be a credible witness seeing the event or an admissible confession from Wagner. As long as he keeps his mouth shut, he’s unlikely to hang himself. That only leaves fresh evidence or a good portrayal of circumstantial evidence.

But what about Robert Wagner’s obvious neglect in searching for Wood as soon as he realized she was missing? It sounds like gross negligence leaving a half-clad, drunken woman out in the dark, cold and rain. However, he can’t be prosecuted for anything other than homicide charges due to California’s Statue of Limitations. That passed three years after Natalie Wood died.

The LA County District Attorney may be able to convince a grand jury to indict Robert Wagner on homicide charges. A coroner’s inquest may also be coming. That may be part of the strategy behind doing the CBS 48 Hours show, and they may have some strong new evidence as the detectives hinted at. But, a homicide conviction requires convincing a jury that Wagner is guilty beyond reasonable doubt of deliberately causing Natalie Wood’s death. That’s a tough challenge for even excellent detectives like Lt. Corina and Det. Sgt. Hernandez.

* * *

DyingWords Followers — I’d really appreciate your comments about how you see the likelihood that Robert Wagner deliberately threw Natalie Wood in the water and caused her death. Please rate them on a scale of 1 (none) to 10 (definitely). It’ll be an interesting poll of public opinion.

DyingWords Followers — I’d really appreciate your comments about how you see the likelihood that Robert Wagner deliberately threw Natalie Wood in the water and caused her death. Please rate them on a scale of 1 (none) to 10 (definitely). It’ll be an interesting poll of public opinion.

Here are some links if you’d like more information on the Natalie Wood death investigation:

CBS 48 Hours Documentary Released February 2018.

Natalie Wood Autopsy Report and Supplementary Opinions from LA County Coroner Office

Natalie Wood Forensic Examination from Los Angeles Times

A conspiracy theory is the belief that a plot by powerful people or an organization is working to accomplish a sinister goal—the truth of its existence secretly held from the public. Conspiracy theorists see authorities—governments, corporations, and wealthy people—as fundamentally deceptive and corrupt. Their distrust of official narratives runs so deep that they connect dots of random events into what they believe make meaningful patterns, despite overwhelming conflicting evidence, or absence of supporting evidence, to their conclusions. Aside from a lack of reason and common sense, what makes crazy conspiracy theorists tick?

A conspiracy theory is the belief that a plot by powerful people or an organization is working to accomplish a sinister goal—the truth of its existence secretly held from the public. Conspiracy theorists see authorities—governments, corporations, and wealthy people—as fundamentally deceptive and corrupt. Their distrust of official narratives runs so deep that they connect dots of random events into what they believe make meaningful patterns, despite overwhelming conflicting evidence, or absence of supporting evidence, to their conclusions. Aside from a lack of reason and common sense, what makes crazy conspiracy theorists tick? 9/11 was a monstrous conspiracy—orchestrated by Bin Laden and al-Qaeda. The Russian Revolution was a conspiracy. So was the American Revolution—fifty-six men signed the Declaration of Independence. Nixon conspired to hide Watergate. Abraham Lincoln was murdered through a conspiracy. So was Julius Caesar. Don’t forget Stalin, the Mexican Drug Cartels, and Scientology. And don’t get me going on Klaus Schwab with his Fourth Industrial Revolution, Davos, and the World Economic Forum.

9/11 was a monstrous conspiracy—orchestrated by Bin Laden and al-Qaeda. The Russian Revolution was a conspiracy. So was the American Revolution—fifty-six men signed the Declaration of Independence. Nixon conspired to hide Watergate. Abraham Lincoln was murdered through a conspiracy. So was Julius Caesar. Don’t forget Stalin, the Mexican Drug Cartels, and Scientology. And don’t get me going on Klaus Schwab with his Fourth Industrial Revolution, Davos, and the World Economic Forum.