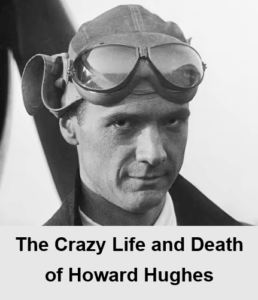

Howard Hughes was a man who could design and test-fly an airplane, direct a movie, seduce a starlet, buy casino hotels, disappear for years, and still make headlines without showing his face. He was as much a symbol of American ambition as he was a cautionary tale of what unchecked wealth, genius, and madness can do to a man. Born into privilege, fueled by obsession, and haunted by demons, Hughes lived a life so extreme that it bordered on mythology. But his death—quiet, grim, and mysterious—might be stranger than the intense living that led to it. Here’s the drama of the crazy life and death of Howard Hughes.

Howard Hughes was a man who could design and test-fly an airplane, direct a movie, seduce a starlet, buy casino hotels, disappear for years, and still make headlines without showing his face. He was as much a symbol of American ambition as he was a cautionary tale of what unchecked wealth, genius, and madness can do to a man. Born into privilege, fueled by obsession, and haunted by demons, Hughes lived a life so extreme that it bordered on mythology. But his death—quiet, grim, and mysterious—might be stranger than the intense living that led to it. Here’s the drama of the crazy life and death of Howard Hughes.

To understand his end, we have to rewind to the beginning of a life lived on the edges of brilliance and breakdown. Howard Hughes was many things: inventor, aviator, filmmaker, billionaire, recluse, suspected intelligence asset, and perhaps most tragically, a prisoner of his own mind.

He died aboard a private jet, his six-foot-four frame weighing only ninety pounds, unrecognizable even to those who’d once worshipped him. The official version says kidney failure. But the deeper you dig, the more the story starts to crack. It was a death as strange as his life—one that still casts a long shadow.

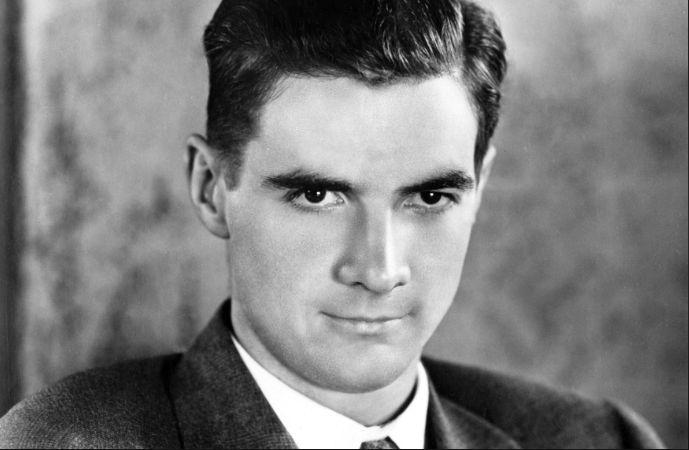

Howard Robard Hughes Jr. was born on December 24, 1905, in Humble, Texas, into a family drenched in oil money. His father, Howard Sr., invented the Hughes rotary drill bit and founded the Hughes Tool Company, which would bankroll young Howard’s endless stream of curiosities and obsessions. By age 11, he built Houston’s first wireless radio transmitter. At 12, he constructed a motorized bicycle from scrap parts. By 14, he was designing working aircraft models in his room. But early brilliance often walks hand in hand with isolation.

Tragedy struck fast and deep. His mother Allene died when he was just 16—reportedly from complications of an ectopic pregnancy. His father died suddenly two years later from a heart attack. At 18, Hughes was a billionaire orphan with complete control over the Hughes Tool fortune. No advisors. No parental guidance. Just money, ambition, and a ticking mind that was already showing cracks.

He dropped out of Rice University and headed west to Los Angeles. Hollywood in the 1920s was wild, wide open, and vulnerable to someone like Hughes: rich, eccentric, and hungry to create. His first film, “Swell Hogan,” was a bomb. But he rebounded with Hell’s Angels, an over-the-top war epic that cost $4 million, used real WWI aircraft, and took three years to complete. Hughes delayed filming repeatedly, waiting for perfect cloud formations to shoot aerial scenes. That level of obsessive control would become his hallmark.

He followed up with The Outlaw (1943), mostly remembered for its promotional posters featuring Jane Russell’s cleavage. Hughes engineered a custom bra for her, designed to lift and frame her bustline more dramatically under studio lights. While Russell later claimed she never wore the thing, Hughes’s reputation as a hyper-controlling, detail-obsessed innovator was sealed. He didn’t just direct movies—he reimagined how to shoot them.

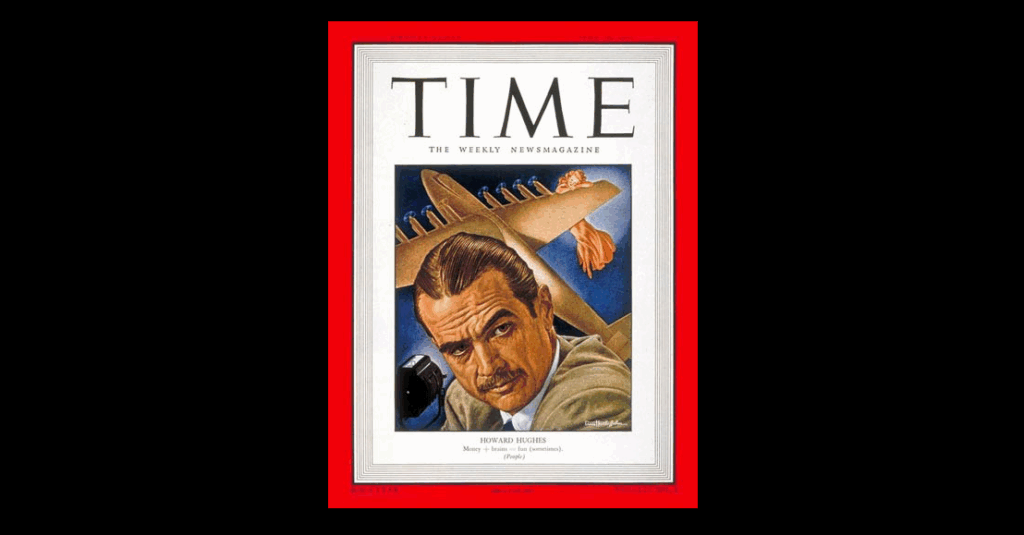

But filmmaking was just the opening act. Hughes’s true passion—perhaps his purest love—was aviation. In 1935, he set a world airspeed record flying the Hughes H-1 Racer. In 1938, he flew around the globe in 91 hours, earning him a ticker-tape parade in New York and a congratulatory telegram from President Franklin D. Roosevelt. His company, Hughes Aircraft, exploded into a major defense contractor, developing radar systems, missiles, and later, aerospace technology. He personally test-piloted many of the prototypes—sometimes successfully, sometimes not.

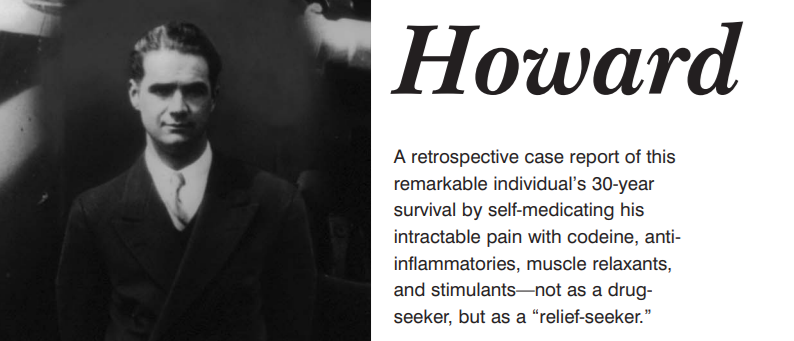

The worst crash came in 1946 while piloting the XF-11 reconnaissance plane over Beverly Hills. He clipped telephone wires and crash-landed in a residential area, destroying several homes. He broke dozens of bones, suffered third-degree burns, and nearly died. He was pulled from the wreckage by a U.S. Marine who happened to live nearby. The physical pain lingered for the rest of his life. So did the emotional trauma.

This is the crash that many believe began driving Howard Hughes crazy.

He emerged from the hospital addicted to morphine, codeine, and later Valium. But the painkillers didn’t just numb the physical agony—they dulled the sharp edges of a mind that was becoming unhinged. He began displaying symptoms that today would be clearly diagnosed: Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD), Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) from repeated crashes, Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI) from head trauma, and likely undiagnosed neurosyphilis, which can cause hallucinations and severe personality changes in its late stages.

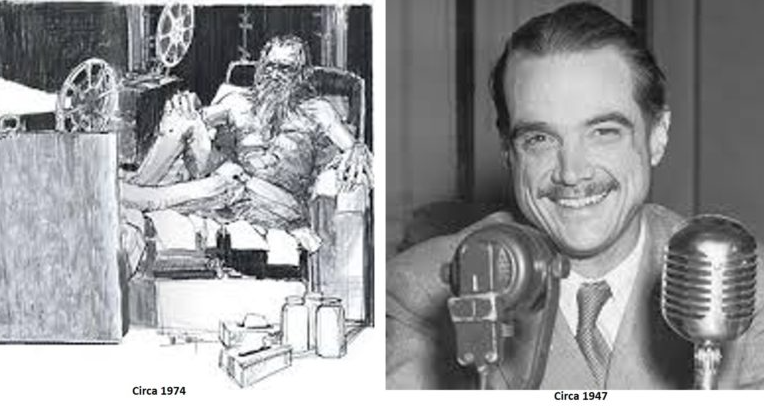

He began spiraling. He became consumed with hand-washing rituals that lasted hours. He insisted on sealed containers for his food. He wrote memos detailing the precise number of tissues someone should use when handling a document. He refused to be touched. And then, gradually, he refused to be seen at all.

By the 1950s, Hughes disappeared from public life. He moved into the Desert Inn hotel in Las Vegas and refused to leave. When the owners threatened eviction, he bought the hotel. Then he bought more—four additional Vegas properties, including the Sands and the Frontier. He watched the city from behind blackout curtains while seated naked in a chair, surrounded by jars of his own urine. He ate the same meal—TV dinners, Hershey bars, and whole milk—every day. For months at a time, he wouldn’t speak. He communicated through written notes. Many were borderline incoherent.

He trusted only a small inner circle of Mormon aides—dubbed the “Mormon Mafia.” These men controlled access to Hughes. They decided who could speak to him, when medications were administered, and even, allegedly, which documents he signed. Whether they were loyal caretakers or self-serving gatekeepers is still up for debate. Some say they protected him. Others believe they manipulated him for their own ends.

Meanwhile, Hughes was still making moves. His influence extended far beyond real estate and film. His company, Hughes Aircraft, was a key contractor for the U.S. government. In 1974, it was revealed that the CIA used Hughes’s name and company to build a deep-sea vessel—the Glomar Explorer—to recover a sunken Soviet submarine. The operation, known as Project Azorian, remains one of the most ambitious and secretive intelligence operations in history. Hughes’s name gave the cover story credibility. It also gave the CIA plausible deniability.

Hughes’s political entanglements didn’t stop there. He had longstanding financial connections to powerful people—most notably Richard Nixon. It’s widely believed that Hughes funneled large sums of money through intermediaries like Bebe Rebozo, a close Nixon ally. Some even argue that the 1972 Watergate break-in was partly motivated by a desire to retrieve sensitive documents linking Nixon to Hughes. Though never definitively proven, the rumors persisted and added another shadow to Hughes’s legacy.

And through it all, he was deteriorating—mentally, physically, and emotionally.

His fingernails grew inches long and curled under themselves. His toenails cracked and yellowed. He refused to bathe or cut his hair. He developed allodynia, a condition where even a soft touch causes extreme pain. He wore Kleenex boxes on his feet and sat naked for days at a time in darkened rooms, watching old movies on repeat. He feared germs, radiation, and even sunlight. His world shrank to a few rooms and a few carefully controlled interactions. He had gone from a bold aviator and innovator to a whisper behind a hotel room door.

In 1972, author Clifford Irving sold a fake Hughes autobiography to publisher McGraw-Hill. Irving claimed he had conducted secret interviews with Hughes. The hoax unraveled spectacularly when Hughes—out of hiding—called in to a press conference and publicly denied any involvement. The voice was unmistakably his. It was the last time the world would ever hear it.

In his final years, Hughes drifted from hotel to hotel, city to city: Managua, Vancouver, Acapulco, London. He traveled by private jet, hidden away, often sedated. His last known photograph is debated. Even his closest aides gave conflicting accounts of where he was at any given time.

On April 5, 1976, Howard Hughes died aboard a chartered Learjet, 30,000 feet over New Mexico, en route from Acapulco to Houston’s Methodist Hospital. He was pronounced dead at 1:27 a.m. The official cause: kidney failure. But when his body was examined, doctors were shocked. He weighed just 90 pounds and had shrunk more than four inches in height. His hair and beard were matted and uncut. His fingernails were several inches long. His skin was covered in sores. He was so unrecognizable, the FBI had to use fingerprints to identify him.

The coroner declared natural causes. But an 18-month private investigation painted a more disturbing picture. According to their report: “Persons unknown intentionally administered a deadly injection of codeine painkiller to this comatose man—obviously needlessly and almost certainly fatal.”

Was it euthanasia? Murder? A mercy killing? Or just gross negligence? We’ll likely never know. But Hughes’s legacy was immediately thrown into chaos. There was no clear will. Dozens of people claimed to have one. Most were forged. One, presented by gas station attendant Melvin Dummar, claimed Hughes had left him $156 million. It was ruled a fake, but the story became the basis for the film Melvin and Howard.

Even in death, Hughes was a myth waiting to be rewritten.

His Howard Hughes Medical Institute—originally established as a tax shelter—became one of the largest and most respected biomedical research organizations in the world. His story inspired books, films (The Aviator among them), and countless conspiracy theories. He remains one of the most complex, contradictory figures in American history.

So, what drove Howard Hughes crazy?

It wasn’t just the painkillers. Or the isolation. Or the crashes. It was the collision of genius without limits, power without oversight, and a mind without rest. He was a man of staggering vision—who could imagine worlds that hadn’t yet been built—but also a man whose compulsions devoured him from the inside out. He chased perfection in everything: flight, film, business, beauty. And perfection, for Hughes, was always just one more note, one more tweak, one more cleaning away.

He died not just from kidney failure—but from the failure of a peripheral support system that let a brilliant man collapse into exponential madness behind closed doors.

This is the real Howard Hughes—the boy genius, the master builder, the spy asset, the germ-fearing recluse, the paranoid mogul, and the man whose life and death still stir questions we may never answer.

And this was the crazy life and death of Howard Hughes.