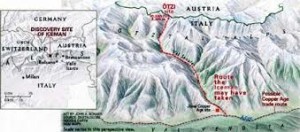

In 1991, the mummified body of a 5,000-year-old murder victim was discovered in melting ice at a rock-gully crime scene high in the Italian Otzal Alps. Nicknamed “Otzi”, the estimated 45-year-old man and his possessions were incredibly well preserved. His skin, hair, bones, and organs were cryopreserved in time, allowing archeological researchers a phenomenal insight into human life in the Copper Age.

In 1991, the mummified body of a 5,000-year-old murder victim was discovered in melting ice at a rock-gully crime scene high in the Italian Otzal Alps. Nicknamed “Otzi”, the estimated 45-year-old man and his possessions were incredibly well preserved. His skin, hair, bones, and organs were cryopreserved in time, allowing archeological researchers a phenomenal insight into human life in the Copper Age.

The frozen-in-time corpse also gave modern science the opportunity to forensically investigate and positively determine how Otzi The Iceman was killed.

On a sunny September day, two hikers were traversing a mountain pass at the 3210 meter (10,530 foot) level and saw a brown, leathery shape protruding from the ice amidst running melt-water. Closely examined, it was a human body which they thought might be the victim of a past mountaineering accident.

On a sunny September day, two hikers were traversing a mountain pass at the 3210 meter (10,530 foot) level and saw a brown, leathery shape protruding from the ice amidst running melt-water. Closely examined, it was a human body which they thought might be the victim of a past mountaineering accident.

They reported it to Austrian police who attended the following day and quickly realized they were dealing with an ancient archeological site. A scientific team was assembled and, over a three-day period, the remains were extracted and taken to the Institute of Forensic Medicine in Innsbruck.

Such an incredibly valuable find soon led to a jurisdictional argument between the Austrian and Italian governments and an immediate border survey was done, finding Otzi had been lying ninety-two meters inside of Italian territory. Italy gained legal possession of the body and artifacts, however in the interests of science and history, everything was kept at Innsbruck until a proper, climate-controlled facility was built at the South Tyrol Museum of Archaeology in Bolzano, Italy, where Otzi the Iceman now rests.

Such an incredibly valuable find soon led to a jurisdictional argument between the Austrian and Italian governments and an immediate border survey was done, finding Otzi had been lying ninety-two meters inside of Italian territory. Italy gained legal possession of the body and artifacts, however in the interests of science and history, everything was kept at Innsbruck until a proper, climate-controlled facility was built at the South Tyrol Museum of Archaeology in Bolzano, Italy, where Otzi the Iceman now rests.

Many, many questions arose. Who was he? Where did he come from? How long ago did he live? And, of course, what caused his death?

Technological advances over the past twenty-five years have answered some questions surrounding Otzi’s life and death and surely the next twenty-five will answer more. This, so far, is what science knows about the Iceman.

Otzi was found lying face down with outstretched arms in a protected, rock depression near the Finail Peak watershed at the top of the Tisenjoch pass which connects two forested valleys. The trench measured 40 meters (131 foot) long, between 5 and 8 meters (16–26 foot) wide, and averaged 3 meters (10 feet) deep. For millennia, this area was covered by glaciers which, by the end of the twentieth century, had receded.

Otzi was found lying face down with outstretched arms in a protected, rock depression near the Finail Peak watershed at the top of the Tisenjoch pass which connects two forested valleys. The trench measured 40 meters (131 foot) long, between 5 and 8 meters (16–26 foot) wide, and averaged 3 meters (10 feet) deep. For millennia, this area was covered by glaciers which, by the end of the twentieth century, had receded.

Four separate scientific institutes conducted C-14 radiocarbon dating on Otzi, equivocally agreeing he came from between 3350 and 3100 BC — more than 5,000 years ago. This was the oldest-known preserved human being; far older than the Egyptian and Inca mummifications or the corpses found pickled in peat bogs.

Something exceptionally unique about Otzi was that he was a “wet” mummy—an almost unheard of process for a cadaver of this age where humidity was preserved in his cells, unlike the intentional dehydration processes used in Egypt and Peru. As well, Otzi was perfectly intact and not dissected or embalmed by a funeral ritual. His entire body achieved a state of elasticity and, although shrunken, remained as in the day he died including vital clues stored in his digestive tract.

Something exceptionally unique about Otzi was that he was a “wet” mummy—an almost unheard of process for a cadaver of this age where humidity was preserved in his cells, unlike the intentional dehydration processes used in Egypt and Peru. As well, Otzi was perfectly intact and not dissected or embalmed by a funeral ritual. His entire body achieved a state of elasticity and, although shrunken, remained as in the day he died including vital clues stored in his digestive tract.

Researchers felt Otzi must have been preserved through a chain of coincidences. It was evident that no damage had been done by predators, scavengers, or insects so it was obvious that the body was covered by snow and/or ice immediately after death. Secondly, the gully lay perpendicular to the main ice flow, allowing the grinding action of the glacier to pass overtop. Thirdly, exposure to air and sunlight was only a brief period before being found by the hikers.

It was vital Otzi remain frozen to avoid an irreversible decomposition and remain intact to preserve his historical significance. This gave researchers limited ability to examine the cadaver as would be done in a conventional autopsy.

A thorough external exam was done in 1991 along with Xray radiography images. Notable was a cut to the back of the right hand which showed early signs of healing as well as breaks to the left ribcage, which had healed, and breaks to the right ribs which were fresh at the time of death. A depression in the skull was thought to be caused by the weight of ice compression and analysis of the only remaining fingernail found that the Beau-Reil Lines, which are like rings on a tree trunk, showed significant stress to his immune system in three periods—16, 13, and 8 weeks before death.

A thorough external exam was done in 1991 along with Xray radiography images. Notable was a cut to the back of the right hand which showed early signs of healing as well as breaks to the left ribcage, which had healed, and breaks to the right ribs which were fresh at the time of death. A depression in the skull was thought to be caused by the weight of ice compression and analysis of the only remaining fingernail found that the Beau-Reil Lines, which are like rings on a tree trunk, showed significant stress to his immune system in three periods—16, 13, and 8 weeks before death.

Other factors told of Otzi’s failing health—understandable for a 45-year-old in the Copper Age who’d then be considered elderly. He suffered from tooth decay, gum disease, and worn joints. What shocked the researchers were the amounts, designs, and placement of tattoos on Otzi’s body. There were 61 separate markings, all made by incisions and insertion of charcoal—not ink as has been used by other cultures for centuries. The locations were consistent with known acupuncture points as practiced for pain relief thought to be discovered by the Chinese two thousand years after Otzi’s existence. It seemed these markings were therapeutic, rather than symbolic.

Other factors told of Otzi’s failing health—understandable for a 45-year-old in the Copper Age who’d then be considered elderly. He suffered from tooth decay, gum disease, and worn joints. What shocked the researchers were the amounts, designs, and placement of tattoos on Otzi’s body. There were 61 separate markings, all made by incisions and insertion of charcoal—not ink as has been used by other cultures for centuries. The locations were consistent with known acupuncture points as practiced for pain relief thought to be discovered by the Chinese two thousand years after Otzi’s existence. It seemed these markings were therapeutic, rather than symbolic.

Despite examination by many leading experts, no exact cause of Otzi’s demise was determined and it was speculated this old man may have fallen, injured himself, then succumbed to the elements. That was until new technology was developed.

One of the great challenges was to examine Otzi endoscopically—that is to look internally at his organs. Special high-precision titanium instruments were invented—steel probes that were inserted through tiny incisions in Otzi’s back. Using computerized navigational aids, the tools were guided to exact spots were evidentiary samples could be taken. This was recorded with a hi-definition camera and an entire 3-D map of the mummy’s thorax and abdomen was made.

One of the great challenges was to examine Otzi endoscopically—that is to look internally at his organs. Special high-precision titanium instruments were invented—steel probes that were inserted through tiny incisions in Otzi’s back. Using computerized navigational aids, the tools were guided to exact spots were evidentiary samples could be taken. This was recorded with a hi-definition camera and an entire 3-D map of the mummy’s thorax and abdomen was made.

Lung and digestive tract contents told a time-of-year travel story through the presence of thirty different pollens which entered Otzi’s body by the food he ate, the water he drank, and the air he breathed.

Most pollens were from trees and indicated he ingested them during a bloom in the late spring or early summer. The locations and digested states of different pollens in different sections of the stomach and intestines showed Otzi had made a climb from the valley floor to the top of the pass where he died within a twenty-four hour period. Pollens in the lower gastrointestinal tract were identified to low elevation trees and pollens in the upper GI were from higher elevation species.

Most pollens were from trees and indicated he ingested them during a bloom in the late spring or early summer. The locations and digested states of different pollens in different sections of the stomach and intestines showed Otzi had made a climb from the valley floor to the top of the pass where he died within a twenty-four hour period. Pollens in the lower gastrointestinal tract were identified to low elevation trees and pollens in the upper GI were from higher elevation species.

So, it was known that Otzi had left the populated valley and headed for high country where he met his death. Speculation rose that he might have been fleeing some danger.

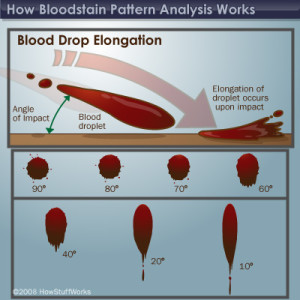

This theory strengthened in 2001 when new Xrays identified a small, flint arrowhead in Otzi’s left shoulder which was missed ten years earlier. A close examination of Otzi’s back revealed a two-centimeter slash and established the arrow’s path. He’d been shot from a rear and lower position.

This theory strengthened in 2001 when new Xrays identified a small, flint arrowhead in Otzi’s left shoulder which was missed ten years earlier. A close examination of Otzi’s back revealed a two-centimeter slash and established the arrow’s path. He’d been shot from a rear and lower position.

In 2005, Otzi was put through a high-resolution, multi-slice CT scanning machine which enlightened the arrow wound. Clearly, the arrowhead had caused a one-centimeter gash in Otzi’s left subclavian artery which is the main circulatory pipeline that carries fresh oxygenated blood from the heart to the left arm. Such a serious tear would have caused massive internal bleeding and rapid death—probably within two minutes.

The CT scan showed something else. There was serious bleeding at the base of the brain which corresponded to the depression in Otzi’s skull. He’d suffered a serious head injury right at the time of death. With the cause of death now certain to be from a violent act of homicide, the prime question centered on the circumstances of how all this went down.

The CT scan showed something else. There was serious bleeding at the base of the brain which corresponded to the depression in Otzi’s skull. He’d suffered a serious head injury right at the time of death. With the cause of death now certain to be from a violent act of homicide, the prime question centered on the circumstances of how all this went down.

Researchers felt the answer may lay in the Iceman’s possessions.

Among the artifacts found on and around Otzi’s body were a copper ax, a flint dagger, a quiver with twelve blank arrow shafts and two completed arrows with stone heads. There was also winter clothing and supplies to support wilderness survival.

Among the artifacts found on and around Otzi’s body were a copper ax, a flint dagger, a quiver with twelve blank arrow shafts and two completed arrows with stone heads. There was also winter clothing and supplies to support wilderness survival.

This speaks to motive, for if robbery was behind Otzi’s murder, it’s certain that the perpetrator(s) would have made off with these valuables. Glaringly missing was the shaft of the fatal arrow, especially in light of Otzi’s quiver arrows being perfectly preserved.

Egarter Vigl, a leading archeological expert on the Iceman, believes that the assailant tried to pull out the fatal arrow to destroy evidence, only to snap off the arrowhead inside. Vigl was quoted in the archeology magazine Germani, “telltale markings in the construction of prehistoric arrows could be used to identify the archer much in the way modern ballistics can link a bullet to a gun. The killer yanked out the arrow to cover his tracks. For similar motives, the attacker did not run off with any precious artifacts that remained at the scene, especially the distinctive copper-bladed ax; the appearance of such a remarkable object in the possession of a villager would automatically implicate its owner of the crime.”

Egarter Vigl, a leading archeological expert on the Iceman, believes that the assailant tried to pull out the fatal arrow to destroy evidence, only to snap off the arrowhead inside. Vigl was quoted in the archeology magazine Germani, “telltale markings in the construction of prehistoric arrows could be used to identify the archer much in the way modern ballistics can link a bullet to a gun. The killer yanked out the arrow to cover his tracks. For similar motives, the attacker did not run off with any precious artifacts that remained at the scene, especially the distinctive copper-bladed ax; the appearance of such a remarkable object in the possession of a villager would automatically implicate its owner of the crime.”

I’d have to agree with Mr. Vigl, and I’d like to add an observation of my own.

In the hundreds and hundreds of dead bodies I’ve examined as a cop and a coroner, I’ve never seen a cadaver with its arms outstretched in a hyperextended position like how Otzi the Iceman was found. This is absolutely unnatural and shrieks to me that someone placed the arms in that position after death.

In the hundreds and hundreds of dead bodies I’ve examined as a cop and a coroner, I’ve never seen a cadaver with its arms outstretched in a hyperextended position like how Otzi the Iceman was found. This is absolutely unnatural and shrieks to me that someone placed the arms in that position after death.

I think it’s safe to speculate on what might have happened and here’s what Otzi’s crime scene evidence suggests to me.

The day before Otzi’s death, he was in a physical altercation down at the village on the valley floor where he suffered the cut hand and possibly the broken right ribs. This caused him to pack up and flee, climbing to the elevated pass where he was overcome by his attacker(s) and shot with the arrow from behind and below. This wound would have put Otzi into hemorrhagic shock and he would have quickly collapsed and internally bled out. Following his collapse, the murderer(s) went up and caved-in the back of Otzi’s head to finish him off.

The day before Otzi’s death, he was in a physical altercation down at the village on the valley floor where he suffered the cut hand and possibly the broken right ribs. This caused him to pack up and flee, climbing to the elevated pass where he was overcome by his attacker(s) and shot with the arrow from behind and below. This wound would have put Otzi into hemorrhagic shock and he would have quickly collapsed and internally bled out. Following his collapse, the murderer(s) went up and caved-in the back of Otzi’s head to finish him off.

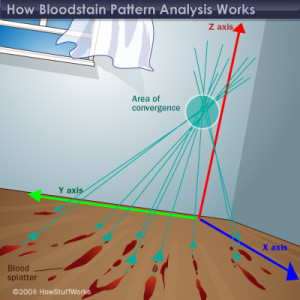

I don’t think this happened in the gully. I’ve looked at the scene photos and can’t envision how Otzi could have been shot from below in that tight gully, which is what the forensic evidence clearly shows on the arrowhead’s track through the body—even if Otzi were bending over.

No, I suspect Otzi was shot elsewhere, dragged by the arms, dumped in the gully with all his possessions, rolled over to remove the arrow, and then covered with ice and/or snow to hide the crime.

No, I suspect Otzi was shot elsewhere, dragged by the arms, dumped in the gully with all his possessions, rolled over to remove the arrow, and then covered with ice and/or snow to hide the crime.

After 5,000 years, the answers to “By who?” and “For what reason?” are unlikely to be known—despite what future technology might bring—and the murder of Otzi the Iceman will always remain a really cold case.