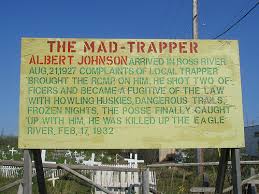

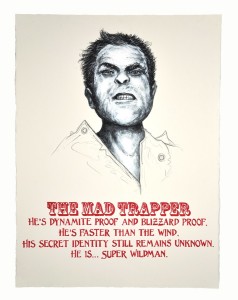

Albert Johnson, known as the Mad Trapper of Rat River, was a murderer and a fugitive from the largest manhunt in the history of Canada, leading a posse of Mounties through the Arctic on a six week, winter wilderness chase in 1932. He killed one Royal Canadian Mounted Police officer and wounded two others before dying from police bullets in a firefight on a frozen river. Today, the Mad Trapper tale is symbolic of the North American frontier. He is an icon. A legend. But was he really Albert Johnson? Find out what modern forensic science tells us.

Albert Johnson, known as the Mad Trapper of Rat River, was a murderer and a fugitive from the largest manhunt in the history of Canada, leading a posse of Mounties through the Arctic on a six week, winter wilderness chase in 1932. He killed one Royal Canadian Mounted Police officer and wounded two others before dying from police bullets in a firefight on a frozen river. Today, the Mad Trapper tale is symbolic of the North American frontier. He is an icon. A legend. But was he really Albert Johnson? Find out what modern forensic science tells us.

The story began on July 9th, 1931, in the Northwest Territories when a stranger arrived in Fort McPherson. Constable Edgar Millen of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police routinely questioned the newcomer who identified himself as ‘Albert Johnson’ but provided no other personal information. Millen satisfied his responsibility to ensure Johnson was equipped for survival in a frontier land with sufficient money and supplies but thought it odd that Johnson declined to buy a trapping license. He noted Johnson was slight of stature, clean in appearance, and spoke with a Scandinavian accent.

The story began on July 9th, 1931, in the Northwest Territories when a stranger arrived in Fort McPherson. Constable Edgar Millen of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police routinely questioned the newcomer who identified himself as ‘Albert Johnson’ but provided no other personal information. Millen satisfied his responsibility to ensure Johnson was equipped for survival in a frontier land with sufficient money and supplies but thought it odd that Johnson declined to buy a trapping license. He noted Johnson was slight of stature, clean in appearance, and spoke with a Scandinavian accent.

Albert Johnson ventured far into the McKenzie Delta and built a small, log cabin on the banks of the Rat River where he reclused. Come the winter, local natives found their traps being raided and concluded the only suspect was Albert Johnson. They complained to the RCMP in Aklavik, causing two Mounties to dog-sled 60 miles through waist-deep snow, arriving at Johnson’s cabin on December 26th, 1931. Johnson was there but refused to speak, forcing the police to return to Aklavik and get a search warrant.

On December 31st four Mounties returned to Rat River. As they attempted to force into Albert Johnson’s shack, he shot at them with a 30-30 Savage rifle, seriously wounding a constable. The police retreated to form a larger posse.

They came back with nine, heavily-armed men, forty-two dogs, and twenty pounds of dynamite. Johnson again opened fire, causing the police to hurl in explosives which blew the cabin apart. Rather than himself also being in pieces, Johnson emerged from a foxhole under the cabin and blasted back with his rifle. A 14-hour standoff, in -40F temperatures, took place until the posse backed-off to Aklavik for more help.

They came back with nine, heavily-armed men, forty-two dogs, and twenty pounds of dynamite. Johnson again opened fire, causing the police to hurl in explosives which blew the cabin apart. Rather than himself also being in pieces, Johnson emerged from a foxhole under the cabin and blasted back with his rifle. A 14-hour standoff, in -40F temperatures, took place until the posse backed-off to Aklavik for more help.

A severe blizzard delayed the return, but on January 14th, 1932, a huge squad of police and civilians arrived to find Albert Johnson long gone. The pursuers caught up with Johnson two weeks later far up the Rat River where Johnson opened fire from a thicket of trees on the bank and shot Constable Edgar Millen dead. Again the police retreated.

By now the news of the manhunt had reached the outer world through an emerging medium called radio. Listeners all over Canada, the United States, and the world, were fixed to their sets to hear the latest on the cat and mouse game between a lone, deranged bushman and the might of the famed Canadian Mounties who ‘always got their man’. It was like the OJ Simpson case of the time.

By now the news of the manhunt had reached the outer world through an emerging medium called radio. Listeners all over Canada, the United States, and the world, were fixed to their sets to hear the latest on the cat and mouse game between a lone, deranged bushman and the might of the famed Canadian Mounties who ‘always got their man’. It was like the OJ Simpson case of the time.

The ‘Arctic Circle War’ represented the end of one era and the beginning of another as the police turned to technology to capture Albert Johnson. They embedded radio into another new tactic – the airplane. World War One flying ace W.R. ‘Wop’ May and his Bellanca monoplane were hired to find Johnson from the air and radio his position to the dogsled and snowshoe team on the ground.

On February 14, May spotted Johnson on the Eagle River in the Yukon Territory, confirming Johnson had traveled an incredible 150 miles, crossing a 7,000-foot mountain pass in white-out conditions, in temperatures with windchill hitting 60 below Fahrenheit. He’d eluded his trackers by wearing snowshoes backward and mingling with migrating caribou herds.

The police overtook Johnson on a river bend on February 17th, 1932. It ended in a mass of bullets leaving another Mountie seriously wounded and Albert Johnson, the Mad Trapper of Rat River, dead on the snow.

The police overtook Johnson on a river bend on February 17th, 1932. It ended in a mass of bullets leaving another Mountie seriously wounded and Albert Johnson, the Mad Trapper of Rat River, dead on the snow.

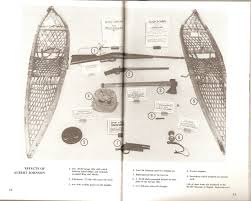

They sledded Johnson’s body back to Aklavik where it was examined, fingerprinted, and photographed. Remarkably, dental examination showed sophisticated, gold bridgework which indicated this man, age estimated at 35 – 40, came from an affluent background. In his effects was $2,410 in Canadian money (worth $34,000 today) but absolutely no documents on his identification. An extensive investigation ensued to find his true identity. His death photos and description were circulated word wide, causing some leads to come in, but nothing definite. No one came forward to claim the body and ‘Albert Johnson’ was buried in a perma-frost grave near the village of Aklavik.

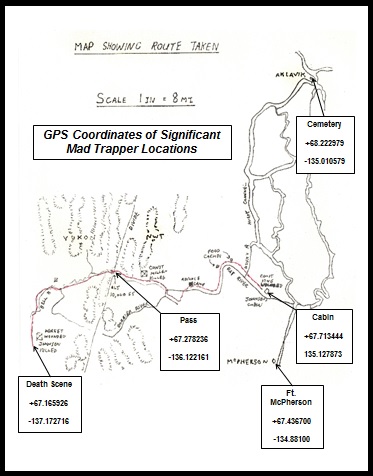

Here are the GPS coordinates for significant Mad Trapper locations.

These latitudes and longitudes can be plugged into iTouch Maps for satellite viewing. https://itouchmap.com/latlong.html

- Cemetery / Gravesite at Aklavik: +68.222979N -135.010579W

- Trapper’s Cabin on Rat River: +67.713444N –135.127873W

- Settlement of Fort McPherson: +67.436700N -134.88100W

- Richardson Mountain Pass: +67.278236N -136.122161W

- Eagle River Death Scene: +67.165926N -137.172716W

The Mad Trapper case was of enormous public interest, many sympathizing how a loner – almost super-human – could endure the environment, living off the land for forty-eight days and outwitting some of the most bush-wise and toughest people of the time. As with the mystery of Albert Johnson’s identity, so was the question of his motive.

The Mad Trapper case was of enormous public interest, many sympathizing how a loner – almost super-human – could endure the environment, living off the land for forty-eight days and outwitting some of the most bush-wise and toughest people of the time. As with the mystery of Albert Johnson’s identity, so was the question of his motive.

Over the years, a number possible identities were offered for who ‘Albert Johnson’ really was.

The most widely accepted theory was Arthur Nelson, a prospector who was known to be in British Columbia from 1927 to 1931 and had left for the Arctic. Photos of Nelson appeared to be a dead-ringer for ‘Albert Johnson’ and descriptions of Nelson’s effects (rifle, pack, and clothing) were identical to those recovered from Johnson.

The most widely accepted theory was Arthur Nelson, a prospector who was known to be in British Columbia from 1927 to 1931 and had left for the Arctic. Photos of Nelson appeared to be a dead-ringer for ‘Albert Johnson’ and descriptions of Nelson’s effects (rifle, pack, and clothing) were identical to those recovered from Johnson.

Another promising lead was a man known as John Johnson, a Norwegian bank robber who’d done time in Folsom Prison. Again, the physical description was similar and the Scandinavian accent noted by Constable Millen seemed to fit.

The Johnson family of Nova Scotia identified the Mad Trapper as their lost relative, Owen Albert Johnson, who was last heard of in British Columbia in the late 1920’s. Again all the pieces fit – physical appearance, personal effects, and disposition.

Sigvald Pedersen Haaskjold was suggested as being the real ‘Albert Johnson’. Haaskjold, who was last seen in northern British Columbia in 1927, was a recluse who was paranoid of authorities because he’d evaded conscription in the First World War. He’d built a fortress-like cabin near Prince Rupert before disappearing. Once more the looks, age, accent, and mentality fit the Trapper’s profile.

Sigvald Pedersen Haaskjold was suggested as being the real ‘Albert Johnson’. Haaskjold, who was last seen in northern British Columbia in 1927, was a recluse who was paranoid of authorities because he’d evaded conscription in the First World War. He’d built a fortress-like cabin near Prince Rupert before disappearing. Once more the looks, age, accent, and mentality fit the Trapper’s profile.

As with advances in 1930’s technology like the radio and the airplane which tracked ‘Albert Johnson’ down, forensic technology in the twenty-first century came into play for a once-and-for-all attempt at solving the mystery of who the Mad Trapper of Rat River really was.

In 2007, seventy-five years after his death, ‘Albert Johnson’ was exhumed for another look. As part of a Discovery Channel documentary, a team of eminent scientists including forensic odontologist and DNA extraction expert Dr. David Sweet, forensic pathologist Dr. Sam Andrews, and forensic anthropologist Dr. Owen Beattie, examined the skeletonized remains.

In 2007, seventy-five years after his death, ‘Albert Johnson’ was exhumed for another look. As part of a Discovery Channel documentary, a team of eminent scientists including forensic odontologist and DNA extraction expert Dr. David Sweet, forensic pathologist Dr. Sam Andrews, and forensic anthropologist Dr. Owen Beattie, examined the skeletonized remains.

This forensic story is every bit as exciting as the hunt for the Trapper himself.

It took a pile of wrangling to get legal approval for exhumation, then obtain the consent of native peoples who laid claim to the land in which the Trapper was interred. Due to permafrost, there was only a slight window of time when the archeological dig could be made. And the exact location of the grave was in doubt.

Perseverance came down to the last available day when the team and film crew zeroed-in on a shallow grave with a rotten, wooden casket. Using archeological skill and precision, the forensic scientists carefully detached the lid and exposed a perfectly preserved male skeleton. There were no longer traces of flesh or fabric, but what gleamed in their faces was gold bridgework from a sneering skull. Dr. Sweet used dental records made in 1932 to positively identify the ghostly remains as that of the Mad Trapper.

Perseverance came down to the last available day when the team and film crew zeroed-in on a shallow grave with a rotten, wooden casket. Using archeological skill and precision, the forensic scientists carefully detached the lid and exposed a perfectly preserved male skeleton. There were no longer traces of flesh or fabric, but what gleamed in their faces was gold bridgework from a sneering skull. Dr. Sweet used dental records made in 1932 to positively identify the ghostly remains as that of the Mad Trapper.

The team cataloged the bones, making three interesting observations. One was a deformity in the spine which led to questions as to how the man could have performed the physical feats described in legend. Second was that one foot was considerably longer than the other, again questioning his mobility. And third was the entry and exit marks of a bullet path through the pelvis which was consistent to the reported fatal wound.

The team had the right remains but were no further ahead in determining identity. Dr. Sweet sectioned the Trapper’s right femur and extracted bone marrow samples as well as pulling four teeth for DNA examination. The remains were replaced in a new casket and re-interred in the original grave.

The team had the right remains but were no further ahead in determining identity. Dr. Sweet sectioned the Trapper’s right femur and extracted bone marrow samples as well as pulling four teeth for DNA examination. The remains were replaced in a new casket and re-interred in the original grave.

Back at the University of British Columbia, Dr. Sweet and his colleagues developed a perfect DNA profile of the Trapper. Extensive field investigation located relatives of the primary suspects – Arthur Nelson, John Johnson, Owen Albert Johnson, and Sigvald Pedersen Haaskjold. Descendant DNA profiles were developed for these men and compared to the known biological signature of the Trapper.

And guess who’s DNA matched?

All four suspects were conclusively eliminated by modern forensic technology as being the Mad Trapper – as were a number of other remote possibilities. One sidenote is that oxygen isotopes developed from the teeth enamel indicated that the Trapper originated from either the mid-western United States or from Scandinavia.

So who really was Albert Johnson, the Mad Trapper of Rat River?

The mystery of who lies in the Aklavik grave remains unsolved.

* * *

Here are links to the fascinating made-for-television documentary on the forensic exhumation of the Mad Trapper’s skeleton.

http://www.mythmerchantfilms.com/index.php/mnu-library/mnu-lib-madtrapper

https://vimeo.com/channels/vidalbdoc/65414821

And author Barbara Smith wrote The Mad Trapper – Unearthing a Mystery which documents the forensic adventure. Click Here