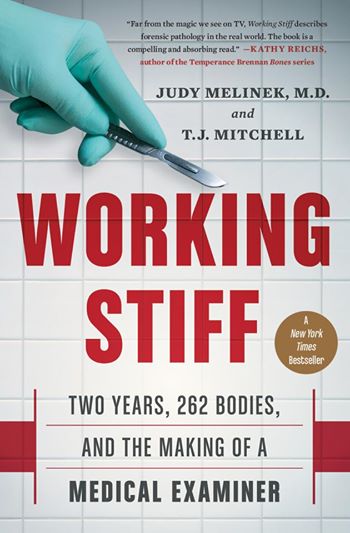

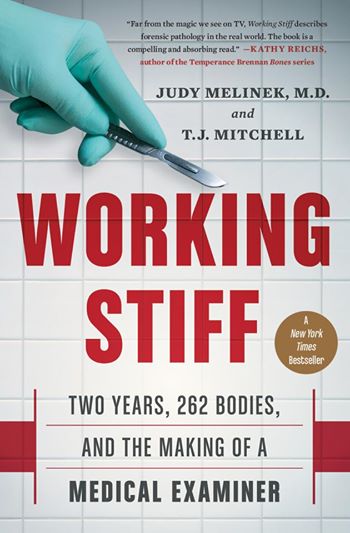

Working Stiff is a new release and New York Times BestSeller by Forensic Pathologist Dr. Judy Melinek and co-authored by her husband T.J. Mitchell. If you want to know what it’s really like behind the morgue door, this is a fascinating read. I’m thrilled to death to have Dr. Melinek do this guest post on Dyingwords.

The CSI effect is a term coined by attorneys for the unrealistic expectations created by television crime shows on the public. It’s a real thing. As an expert witness in forensic pathology I see the CSI effect when I’m faced with questions like, “Why can’t you tell us the precise time of death down to the minute, like on TV?”

The CSI effect is a term coined by attorneys for the unrealistic expectations created by television crime shows on the public. It’s a real thing. As an expert witness in forensic pathology I see the CSI effect when I’m faced with questions like, “Why can’t you tell us the precise time of death down to the minute, like on TV?”

Potential jurors are now being asked if they watch NCIS, CSI, Bones, Law & Order: Criminal Intent, and a plethora of other shows that depict police and other forensic professionals doing their jobs. So how close are these shows to reality? I’m here to tell you. Here are 7 things these shows consistently get wrong:

1. Somebody Turn on the Lights!

The first thing the police do when they secure a crime scene outdoors is set up Klieg lights to illuminate the scene while we do our work there. When I get to an indoor death scene and the lights are off? Well, we turn on the lights. Television shows striving to effect an atmosphere of suspense portray the crime scene investigators looking around a death scene with flashlights. Back at the lab, it’s gloomy and dim. The scientist is wearing a headlamp while he pokes at something bloody but indistinct. Seriously? Forensic science is done in a clean and bright lab. My autopsy suite in the morgue has the same overhead lighting as a surgery suite, with good reason: I need to see what I’m cutting. You can’t find the evidence if you can’t see the evidence, and without evidence there is no forensic case.

The first thing the police do when they secure a crime scene outdoors is set up Klieg lights to illuminate the scene while we do our work there. When I get to an indoor death scene and the lights are off? Well, we turn on the lights. Television shows striving to effect an atmosphere of suspense portray the crime scene investigators looking around a death scene with flashlights. Back at the lab, it’s gloomy and dim. The scientist is wearing a headlamp while he pokes at something bloody but indistinct. Seriously? Forensic science is done in a clean and bright lab. My autopsy suite in the morgue has the same overhead lighting as a surgery suite, with good reason: I need to see what I’m cutting. You can’t find the evidence if you can’t see the evidence, and without evidence there is no forensic case.

2. Where Do You Shop?

Low cut blouses and high-hemmed skirts are not appropriate attire at a crime scene. Neither are stiletto heels, platform heels—any heels. You don’t want to wobble or trip when you’re negotiating your way around a corpse on the sidewalk, believe me. Police departments and sheriff-coroners have strict dress codes and grooming rules with restrictions on hairstyles and visible tattoos. You can lose your credibility as a forensic professional if you are not wearing business attire. And one more thing: No Louboutinson a government salary.

Low cut blouses and high-hemmed skirts are not appropriate attire at a crime scene. Neither are stiletto heels, platform heels—any heels. You don’t want to wobble or trip when you’re negotiating your way around a corpse on the sidewalk, believe me. Police departments and sheriff-coroners have strict dress codes and grooming rules with restrictions on hairstyles and visible tattoos. You can lose your credibility as a forensic professional if you are not wearing business attire. And one more thing: No Louboutinson a government salary.

3. Don’t You Have Anything Else to Do?

Most forensic science jobs, whether in an office or the lab, are nine-to-five. As we say in the morgue at quitting time, “They’ll still be dead tomorrow.” There is no need to come in at two in the morning to run a lab test because you just can’t sleep until you do, or to perform an entire autopsy, alone, in the middle of the night. In fact, most offices have restrictions on entering after hours, and any technician or employee who is poking around in the lab without supervision will encounter serious scrutiny. It’s true that police officers work unorthodox hours, but they do so on a shift schedule and overtime is monitored. When the shift ends they pass the case to another investigator, go home to their families, or to bed to sleep, or off to do ordinary things like normal human beings. Unlike their television avatars, they do not single-handedly conduct an investigation around the clock.

Most forensic science jobs, whether in an office or the lab, are nine-to-five. As we say in the morgue at quitting time, “They’ll still be dead tomorrow.” There is no need to come in at two in the morning to run a lab test because you just can’t sleep until you do, or to perform an entire autopsy, alone, in the middle of the night. In fact, most offices have restrictions on entering after hours, and any technician or employee who is poking around in the lab without supervision will encounter serious scrutiny. It’s true that police officers work unorthodox hours, but they do so on a shift schedule and overtime is monitored. When the shift ends they pass the case to another investigator, go home to their families, or to bed to sleep, or off to do ordinary things like normal human beings. Unlike their television avatars, they do not single-handedly conduct an investigation around the clock.

4. You’re Dating Who?

Why are TV forensic scientists always flirting or sleeping with cops and co-workers? Dating someone you met on the job is taboo in most professions, and even more so in a field where your work is subject to legal scrutiny. If you are caught canoodling with a co-worker you could find yourself under investigation from—no pun intended—internal affairs, and if IA finds either of you has been influenced or biased by your fraternization you could both lose your jobs. Yes, television series need steamy subplots, but do they all have to involve intramural romance?

Why are TV forensic scientists always flirting or sleeping with cops and co-workers? Dating someone you met on the job is taboo in most professions, and even more so in a field where your work is subject to legal scrutiny. If you are caught canoodling with a co-worker you could find yourself under investigation from—no pun intended—internal affairs, and if IA finds either of you has been influenced or biased by your fraternization you could both lose your jobs. Yes, television series need steamy subplots, but do they all have to involve intramural romance?

5. Lab Results!

DNA results in crime shows come back while the body is still warm, and the toxicology report is ready before the bone saw is even fired up. Someone please tell me where these labs with five minute turn-around-times are, because I want to send my specimens there! Tox results take a minimum of two weeks in the best labs, and DNA can take months to come back. Meanwhile, the autopsy paperwork gets filed and we wait for the results to come back before we conclude anything.

DNA results in crime shows come back while the body is still warm, and the toxicology report is ready before the bone saw is even fired up. Someone please tell me where these labs with five minute turn-around-times are, because I want to send my specimens there! Tox results take a minimum of two weeks in the best labs, and DNA can take months to come back. Meanwhile, the autopsy paperwork gets filed and we wait for the results to come back before we conclude anything.

6. Where Are Your PPEs?

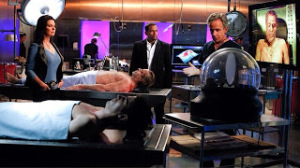

Left – Television Right – Real Autopsy Gear

PPE is personal protective equipment: gloves, face shields, masks and Tyvek suits, gear worn by forensic professionals while performing autopsies to keep themselves safe from blood-borne pathogens and potentially transmissible emerging infectious diseases. But PPE is notably absent on most shows, probably because directors want to see the actors’ faces. Showing emotion with your eyes, body language and tone of voice is not sufficient? If I am pissed off at someone in the morgue that’s what I do, and it seems to work just fine. OSHA would shut down these imaginary TV labs in a New York minute over these high-risk and needless violations. Nobody eats in the lab anymore either. That was something they did back in the days of Quincy ME, but it can get you fired nowadays.

And, finally…

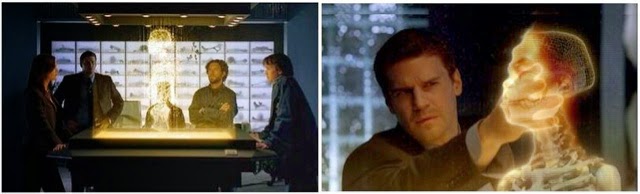

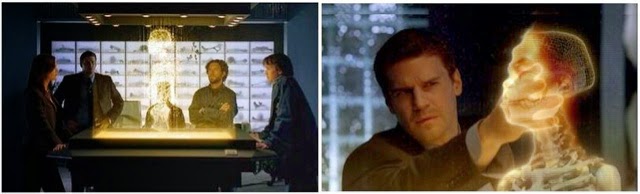

7. Where Can I Get Me One of These?

Most crime labs and autopsy facilities in the United States are underfunded. We are lucky to be working with basic equipment, like an X-ray machine that works reliably, and we don’t have access to the highfalutin gadgets these lucky TV scientists enjoy. Things like 3-D holographic reconstructions exist in digital-simulation labs at academic institutions, and may be used to publish papers on virtual autopsies in foreign countries, but such doodads are not available to the forensic civil servants who are doing the actual, daily work in the real world. In my autopsy suite I handle tools you will recognize from your kitchen. It’s the ultimate in hands-on investigation. I love my job. And I’d love to see it portrayed in fiction with more accuracy—because the reality of forensic death investigation is even more riveting than the fantasy as seen on TV.

Most crime labs and autopsy facilities in the United States are underfunded. We are lucky to be working with basic equipment, like an X-ray machine that works reliably, and we don’t have access to the highfalutin gadgets these lucky TV scientists enjoy. Things like 3-D holographic reconstructions exist in digital-simulation labs at academic institutions, and may be used to publish papers on virtual autopsies in foreign countries, but such doodads are not available to the forensic civil servants who are doing the actual, daily work in the real world. In my autopsy suite I handle tools you will recognize from your kitchen. It’s the ultimate in hands-on investigation. I love my job. And I’d love to see it portrayed in fiction with more accuracy—because the reality of forensic death investigation is even more riveting than the fantasy as seen on TV.

For more about real death investigation don’t miss “Working Stiff: Two Years, 262 bodies and the Making of a Medical Examiner” by Judy Melinek, M.D. and T.J. Mitchell. It’s been available on-line and in stores since August 12, 2014. For updates check in with Facebook/DrWorkingStiff or at www.drworkingstiff.com. Follow @drjudymelinek and@tjmitchellws on Twitter.

For more about real death investigation don’t miss “Working Stiff: Two Years, 262 bodies and the Making of a Medical Examiner” by Judy Melinek, M.D. and T.J. Mitchell. It’s been available on-line and in stores since August 12, 2014. For updates check in with Facebook/DrWorkingStiff or at www.drworkingstiff.com. Follow @drjudymelinek and@tjmitchellws on Twitter.

Get Working Stiff at http://www.pathologyexpert.com/working-stiff-book/

AMAZON LINK for Print, eBook & Audiobook at http://www.amazon.com/Working-Stiff-Bodies-Medical-Examiner-ebook/dp/B00GEEB8GQ

Here’s an excerpt from Working Stiff –

Chapter One – This Can Only End Badly

“Remember: This can only end badly.” That’s what my husband says anytime I start a story. He’s right.

So. This carpenter is sitting on a sidewalk in Midtown Manhattan with his buddies, half a dozen subcontractors in hard hats sipping their coffees before the morning shift gets started. The remains of a hurricane blew over the city the day before, halting construction, but now it’s back to business on the office tower they’ve been building for eight months.

As the sun comes up and the traffic din grows, a new noise punctures the hum of taxis and buses: a metallic creak, not immediately menacing. The creak turns into a groan, and somebody yells. The workers can’t hear too well over the diesel noise and gusting wind, but they can tell the voice is directed at them. The groan sharpens to a screech. The men look up—then jump to their feet and sprint off, their coffee flying everywhere. The carpenter chooses the wrong direction.

With an earthshaking crash, the derrick of a 383-foot-tall construction crane slams down on James Friarson’s head.

I arrived at this gruesome scene two hours later with a team of MLIs, medicolegal investigators from the New York City Office of Chief Medical Examiner. The crane had fallen directly across a busy intersection at rush hour and the police had shut it down, snarling traffic in all directions. The MLI driving the morgue van cursed like a sailor as he inched us the last few blocks to the cordon line. Medicolegal investigators are the medical examiner’s first responders, going to the site of an untimely death, examining and documenting everything there, and transporting the body back to the city morgue for autopsy. I was starting a monthlong program designed to introduce young doctors to the world of forensic death investigation and had never worked outside a hospital. “Doc,” the MLI behind the wheel said to me at one hopelessly gridlocked corner, “I hope you don’t turn out to be a black cloud. Yesterday all we had to do was scoop up one little old lady from Beth Israel ER. Today, we get this clusterfuck.”

“Watch your step,” a police officer warned when I got out of the van. The steel boom had punched a foot-deep hole in the sidewalk when it came down on Friarson. A hard hat was still there, lying on its side in a pool of blood and brains, coffee and doughnuts. I had spent the previous four years training as a hospital pathologist in a fluorescent-lit world of sterile labs and blue scrubs. Now I found myself at a windy crime scene in the middle of Manhattan rush hour, gore on the sidewalk, blue lights and yellow tape, a crowd of gawkers, grim cops, and coworkers who kept using the word “clusterfuck.”

I was hooked.

See more at: http://books.simonandschuster.com/Working-Stiff/Judy-Melinek-MD/9781476727257/excerpt#sthash.ToVVB0WO.dpuf

About the Authors

Judy Melinek, M.D. is a graduate of Harvard University. She trained at UCLA in medicine and pathology, graduating in 1996. Her training at the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner in New York is the subject of her memoir, Working Stiff, which she co-wrote with her husband. Currently, Dr. Melinek is an Assistant Clinical Professor at UCSF, and works as a forensic pathologist in San Francisco. She also travels nationally and internationally to lecture on anatomic and forensic pathology and she has been consulted as a forensic expert in many high-profile legal cases, as well as for the television shows E.R. and Mythbusters.

Judy Melinek, M.D. is a graduate of Harvard University. She trained at UCLA in medicine and pathology, graduating in 1996. Her training at the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner in New York is the subject of her memoir, Working Stiff, which she co-wrote with her husband. Currently, Dr. Melinek is an Assistant Clinical Professor at UCSF, and works as a forensic pathologist in San Francisco. She also travels nationally and internationally to lecture on anatomic and forensic pathology and she has been consulted as a forensic expert in many high-profile legal cases, as well as for the television shows E.R. and Mythbusters.

T.J. Mitchell, her husband, graduated with an English degree from Harvard and has worked as a screenwriter’s assistant and script editor since 1991. He is a writer and stay-at-home Dad raising their three children in San Francisco. His consult practice, T.J. Mitchell Consulting, offers advice to aspiring screenwriters. Working Stiff is his first book.

T.J. Mitchell, her husband, graduated with an English degree from Harvard and has worked as a screenwriter’s assistant and script editor since 1991. He is a writer and stay-at-home Dad raising their three children in San Francisco. His consult practice, T.J. Mitchell Consulting, offers advice to aspiring screenwriters. Working Stiff is his first book.

Dr. Melinek is a American Board of Pathology board-certified forensic pathologist practicing forensic medicine in San Francisco, California as well as an Assistant Clinical Professor of Pathology at the UCSF Medical Center.

Dr. Melinek trained in Pathology at University of California, Los Angeles and then as a forensic pathologist at the New York City Medical Examiner’s Office from 2001-2003. She has consulted and testified in criminal and civil cases in Alaska, Arizona, California, Florida, Illinois, Louisiana, Maryland, Mississippi, New Mexico, New York, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Texas and Washington.

Dr. Melinek has been qualified as an expert witness in forensic pathology, neuropathology and wound interpretation. She has had subspecialty training in surgery and has published and consulted on cases of medical malpractice and therapeutic complications. She trains doctors and attorneys on forensic pathology, proper death reporting and certification. She has been invited to lecture at professional conferences on the subjects of death certification, complications of therapy, forensic toxicology and in-custody deaths. She has also published extensively in the peer-reviewed literature on subjects of surgical complications, death following gastric bypass, forensic toxicology, opioid overdose deaths, immunology, neuropathology and transplant surgery.

Past clients include the Santa Clara County District Attorney, Office of the County Counsel County of Contra Costa, Marin County Public Defender, the Court Appointed Attorney Program of the Alameda County Bar Association, the Attorney General of the State of California, the United States Military, and many private civil plaintiff’s and defense attorneys. Dr. Melinek travels locally in Northern California to testify in and around the Bay Area including San Mateo, Santa Clara, Marin, Monterey, Napa, Lake, Shasta, Solano, Sonoma and Stanislaus Counties. She has also been called to Southern California to review cases in Los Angeles, San Bernadino, Riverside, Ventura and San Diego Counties.

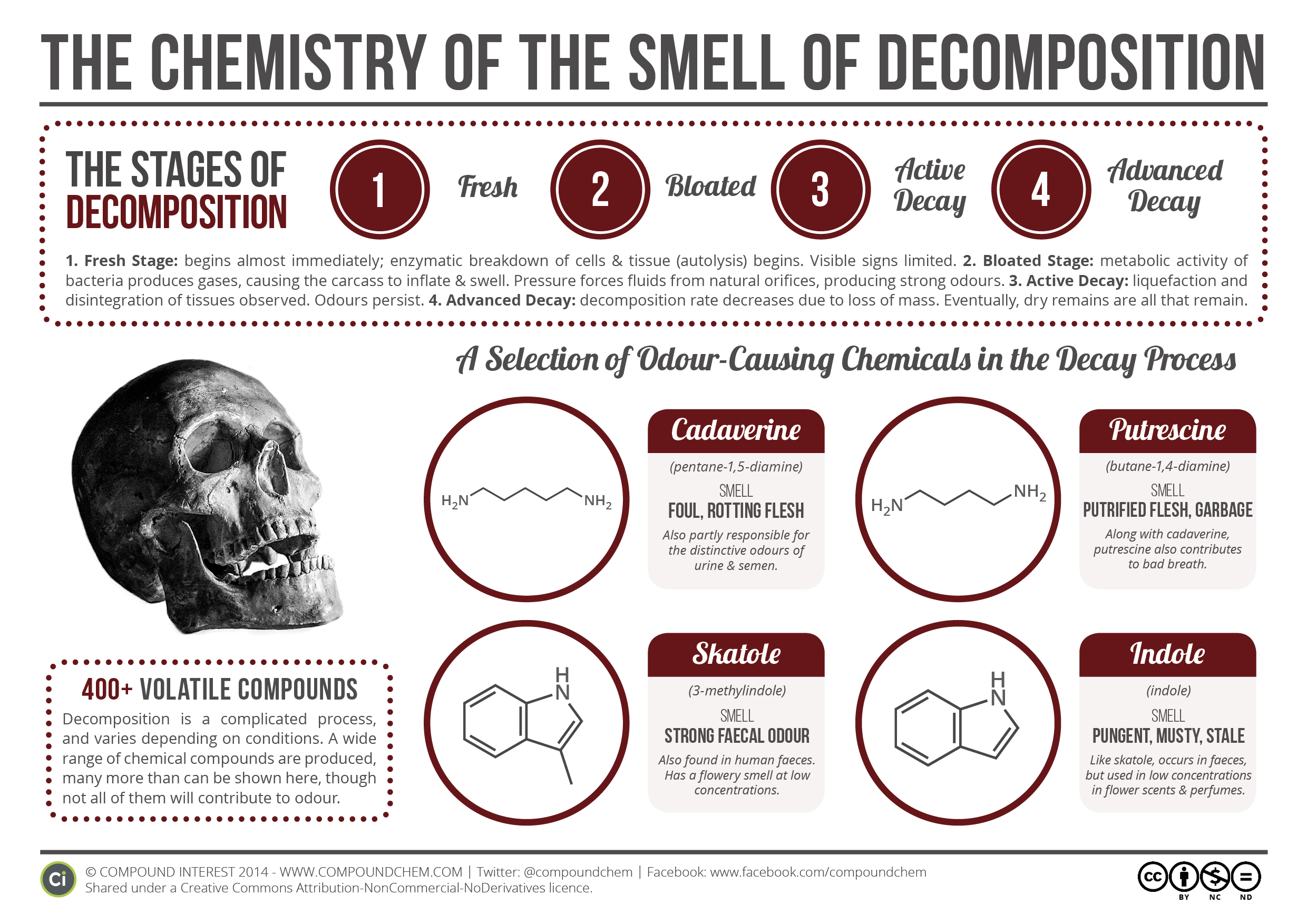

Decomposition is an incredibly complicated process, but we do know a little about the chemical culprits behind some of the terrible smells as the body breaks down.

Decomposition is an incredibly complicated process, but we do know a little about the chemical culprits behind some of the terrible smells as the body breaks down.  Once the heart has stopped beating, the cells in the body are deprived of oxygen. As carbon dioxide and waste products build up, the cells start to break down as a result of enzymatic processes – these are known as autolysis. Initial visual signs of decomposition are minimal, although as autolysis progresses blisters and sloughing of skin may occur.

Once the heart has stopped beating, the cells in the body are deprived of oxygen. As carbon dioxide and waste products build up, the cells start to break down as a result of enzymatic processes – these are known as autolysis. Initial visual signs of decomposition are minimal, although as autolysis progresses blisters and sloughing of skin may occur. As a result of the bloating, the increased pressure causes bodily fluids to be forced out of natural orifices, as well as potentially causing ruptures in the skin. This can cause a formidable odour; at this stage, if insects are able to access the body, flies will lay eggs in exposed orifices, which will in turn hatch into maggots which then devour the flesh.

As a result of the bloating, the increased pressure causes bodily fluids to be forced out of natural orifices, as well as potentially causing ruptures in the skin. This can cause a formidable odour; at this stage, if insects are able to access the body, flies will lay eggs in exposed orifices, which will in turn hatch into maggots which then devour the flesh. These factors also have an effect on the large number of compounds produced during the decomp process. Considering that, as a species, we’ve been dying and decomposing for thousands of years, we know surprisingly little about the specifics of the process and the chemicals involved.

These factors also have an effect on the large number of compounds produced during the decomp process. Considering that, as a species, we’ve been dying and decomposing for thousands of years, we know surprisingly little about the specifics of the process and the chemicals involved. Skatole, as you may have already guessed from the name, has a strong odour of faeces, whilst indole has a mustier, mothball-like smell. Both compounds are found in human and animal faeces, so it’s little surprise that they can contribute unpleasantness to the odour of a decomposing corpse. The strange thing about both is that, at low concentrations, they actually have quite pleasant, flowery aromas, leading to an array of unexpected uses. Indole is found in jasmine oil, which is used in many perfumes, whilst synthetic skatole is used in small amounts as a flavouring in ice creams, as well as also being found in perfumes.

Skatole, as you may have already guessed from the name, has a strong odour of faeces, whilst indole has a mustier, mothball-like smell. Both compounds are found in human and animal faeces, so it’s little surprise that they can contribute unpleasantness to the odour of a decomposing corpse. The strange thing about both is that, at low concentrations, they actually have quite pleasant, flowery aromas, leading to an array of unexpected uses. Indole is found in jasmine oil, which is used in many perfumes, whilst synthetic skatole is used in small amounts as a flavouring in ice creams, as well as also being found in perfumes. Produced by the action of bacteria, compounds such as hydrogen sulfide (which smells of rotten eggs), methanethiol (rotting cabbage), dimethyl disulfide (garlic-like) and dimethyl trisulfide (foul/garlic) all add to the unpleasant scent. A whole range of other compounds are also produced as the tissues of the body decompose – some studies have identified over 400 different compounds, although not all of these will be contributors to the odour.

Produced by the action of bacteria, compounds such as hydrogen sulfide (which smells of rotten eggs), methanethiol (rotting cabbage), dimethyl disulfide (garlic-like) and dimethyl trisulfide (foul/garlic) all add to the unpleasant scent. A whole range of other compounds are also produced as the tissues of the body decompose – some studies have identified over 400 different compounds, although not all of these will be contributors to the odour. Using human corpses in research on decomp is limited in many countries for ethical reasons, so in many studies pigs are used as models. In the USA, however, there are a number of ‘body farms’ – facilities set up in a several states to study decomposition of human remains. The bodies they study are those who have chosen to donate their remains; these are then allowed to decay in a range of conditions and studied as they do so. This can help researchers determine the appearance and chemical emissions of bodies at various stages of decay, which can then inform police investigations where bodies are discovered, helping to determine a more accurate time of death.

Using human corpses in research on decomp is limited in many countries for ethical reasons, so in many studies pigs are used as models. In the USA, however, there are a number of ‘body farms’ – facilities set up in a several states to study decomposition of human remains. The bodies they study are those who have chosen to donate their remains; these are then allowed to decay in a range of conditions and studied as they do so. This can help researchers determine the appearance and chemical emissions of bodies at various stages of decay, which can then inform police investigations where bodies are discovered, helping to determine a more accurate time of death.