This guest post is by Dr. Kim Foster who is a practising physician, a published author, and a mom. She’s also an active health blogger.

Just in time for NaNoWriMo (National Novel Writing Month) I thought I’d do a post about how to write a first draft.

Just in time for NaNoWriMo (National Novel Writing Month) I thought I’d do a post about how to write a first draft.

Because let’s face it, first drafts are hard.

It’s no secret, it’s not my favorite part of the process. I love the outlining / dreaming / planning stages, and I love the revising / shaping / polishing stages. The first draft stage? Not so much.

But it’s okay. It has to get done. Here are my seven tips for conquering that first draft.

1. Carve out the time.

Seems obvious, right? If you want to write a novel, you’re going to have to find the time in your schedule…somewhere. It just won’t get done otherwise. The world is filled with people who dream of writing a novel, someday, when they find the time. Don’t be one of those people.

Seems obvious, right? If you want to write a novel, you’re going to have to find the time in your schedule…somewhere. It just won’t get done otherwise. The world is filled with people who dream of writing a novel, someday, when they find the time. Don’t be one of those people.

We all have time challenges, and the solution will be different for everyone.

That said, I have lots of thoughts on how to find the time to write. It’s something I have wrestled with, and found many solutions for (and continue to find solutions for, in this ever-changing life).

During my blog tour a few months ago I wrote a guest post on how to find the time to write. If you’re struggling with this issue, start there.

2. Forget about quality, just get it done.

To get your first draft finished, you simply have to write. You have to get it down. Why? Because, as Nora Roberts wisely said, “You can’t edit a blank page.”

My first drafts are absolutely horrible. They’re barely literate, filled with little notes and reminders to myself—stuff I know I’ll tackle in subsequent drafts (like: “describe sights and smells of the market here…”). I do that because speed is important to me in a first draft. I think there’s a certain momentum you need to achieve when writing a first draft, because it’s so easy to get sidetracked and distracted. Writing a first draft is a whole lot harder than, say, binge watching Game of Thrones.

My first drafts are absolutely horrible. They’re barely literate, filled with little notes and reminders to myself—stuff I know I’ll tackle in subsequent drafts (like: “describe sights and smells of the market here…”). I do that because speed is important to me in a first draft. I think there’s a certain momentum you need to achieve when writing a first draft, because it’s so easy to get sidetracked and distracted. Writing a first draft is a whole lot harder than, say, binge watching Game of Thrones.

So first drafts should be pretty bad. I’m not alone in thinking this.

“The first draft of anything is shit.” -Ernest Hemingway

“Almost all good writing begins with terrible first efforts. You need to start somewhere.” -Anne Lamott

Cut yourself some slack and just get those words down. You will have plenty of time to rewrite and hack it apart and flesh out the sensory descriptions of markets…but that will come later. First, just get the story down.

3. Don’t worry about balancing the elements of fiction.

Here I’m referring to all the weaving and layering that needs to occur in a finished novel. Your polished novel needs to contain a balance of character stuff, dialogue, narrative, flashbacks, backstory…and much more.

Here I’m referring to all the weaving and layering that needs to occur in a finished novel. Your polished novel needs to contain a balance of character stuff, dialogue, narrative, flashbacks, backstory…and much more.

But trying to keep all that in mind while you’re throwing down the first draft is making it harder than it needs to be.

Just keep telling the story, and worry about those things later.

If you get to a spot where you know you want a certain element—a little bit of character development, say—but you don’t want to slow down, just jot a note to yourself to flesh out that bit on a subsequent draft.

Especially if you’re a pantser, once you’ve got the first draft down, and you know how it all shakes out, you’ll be able to go back and add those elements much more effectively.

Now, it should be said that some people have the ability to do the balance thing in their first draft. And if you’re one of those people, well—go, you! My critique partner, Karma Brown (whose debut comes out in May 2015, by the way) has an amazing ability to get all those components down in her first draft. I actually don’t know how she does it.

Now, it should be said that some people have the ability to do the balance thing in their first draft. And if you’re one of those people, well—go, you! My critique partner, Karma Brown (whose debut comes out in May 2015, by the way) has an amazing ability to get all those components down in her first draft. I actually don’t know how she does it.

When I went to New York this summer for Thrillerfest I listened in shock as Lee Child said “I’m a one-draft writer.”

But most writers—me included—need to weave in those layers and threads during the revision process, and that’s completely okay. Revising in layers is the approach I take, and it’s what many of us do.

4. Don’t think about pacing.

Here I’m talking about both the pacing within a scene, and the overall pacing of the story. Neither issue needs to be dealt with during the first draft. That’s because it’s something best analyzed once you’ve got the whole story down. During the first draft, don’t sweat it.

As you’re writing the first draft, you may reach a scene you can clearly envision, so your descriptions will be deeper and your dialogue more fleshed out. You may not have other scenes figured out quite so fully, so your treatment of them—on first pass—will be more cursory at this point.

As you’re writing the first draft, you may reach a scene you can clearly envision, so your descriptions will be deeper and your dialogue more fleshed out. You may not have other scenes figured out quite so fully, so your treatment of them—on first pass—will be more cursory at this point.

You may also have a string of slow, reflective scenes back to back, and then a run of action scenes…which may not be the pace you’re going for.

That’s okay; it will all get sorted out in subsequent drafts.

During revision, you’ll be able to consider the entire structure of the book and how each scene fits in. Pacing will be different for every book, of course, depending on genre and the particulars of your story.

5. Don’t worry about voice.

I consider the first draft to be about finding the voice for the story. And I don’t mean POV. That’s different. It’s probably a good idea to decide who is telling the story before you start—but depending on how much of a pantser you are, you may not even have that figured out yet.

I consider the first draft to be about finding the voice for the story. And I don’t mean POV. That’s different. It’s probably a good idea to decide who is telling the story before you start—but depending on how much of a pantser you are, you may not even have that figured out yet.

No, when I say “voice” I mean that difficult-to-describe quality of…the sound of the story.

Is it spare and lean, or flowery? Sarcastic? Hard-boiled? Snappy? Poetic?

I read an article somewhere that listed the things you needed to have figured out before starting to write your first draft, and voice was one of the first. My palms grew sweaty at the idea. How can you possibly have the voice determined before writing the draft? I wondered.

There are many things I know (or think I know) before writing: the main characters, the climax, the ending, key scenes. But the voice? Nope. That evolves for me as I’m writing the first draft. It comes out of character as I’m telling the story.

Plus, I think if you worry too much about having a cohesive voice before you even start, it’s going to slow you down while you’re writing that first draft. You’re going to keep stopping and wondering if your voice is consistent, you know?

Plus, I think if you worry too much about having a cohesive voice before you even start, it’s going to slow you down while you’re writing that first draft. You’re going to keep stopping and wondering if your voice is consistent, you know?

Ideally, by the time you’re finished your first draft, the voice has emerged. And then, cleaning up, honing, and polishing that voice becomes a revising layer.

6. Give yourself a deadline.

I think this is a big part of the success of NaNoWriMo. Because NaNo creates a clearly defined—but do-able—timeframe. And although it’s all completely voluntary, there’s something about the accountability to the community that applies needed pressure.

Without a deadline—whether self-imposed or detailed in a book contract—writing a first draft tends to stretch on and on.

Oh, I’ll finish my book…eventually.

A deadline lights a fire. If you’re organized, a deadline means you need to meet a word quota, whether it’s a daily or weekly quota. It keeps you from straying.

A deadline lights a fire. If you’re organized, a deadline means you need to meet a word quota, whether it’s a daily or weekly quota. It keeps you from straying.

So, impose a deadline. Make yourself accountable. Create a pact with a writing partner or your critique group. Join NaNo or another writing challenge. Whatever it takes.

The pressure of a deadline can mean the difference between finishing that book and being one of those eventually people.

7. Keep moving forward.

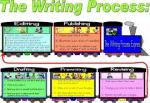

Think of your first draft as a train going in one direction only. Don’t go backwards and re-do stuff while you’re in the middle of your first draft. That’s another good way to never finish a book. If you get caught up on tweaking and polishing and thinking about things too much, and you’ll never get the book written.

Think of your first draft as a train going in one direction only. Don’t go backwards and re-do stuff while you’re in the middle of your first draft. That’s another good way to never finish a book. If you get caught up on tweaking and polishing and thinking about things too much, and you’ll never get the book written.

Keep moving forward and get the whole story out.

Have faith that you will go back and change many things. Resist the temptation to re-read what you’ve written. You will probably be horrified by what you see (refer to point number 2, above), and nobody needs that.