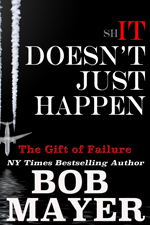

Bob Mayer is a US Army West Point graduate, Green Beret Special Forces veteran, and a prolific writer, publisher, and teacher. He’s also a down-to-earth guy who’s mission is to help others succeed. Thanks, Bob, for sharing your experience about preparing for chaos.

Catastrophe planning in the civilian world is primarily the province of engineers and management. The problem with that is engineers and management are trained for, plan for, and work in a controlled environment (what they think is a controlled environment). So delusion events are outside their comfort zone; aberrations.

Catastrophe planning in the civilian world is primarily the province of engineers and management. The problem with that is engineers and management are trained for, plan for, and work in a controlled environment (what they think is a controlled environment). So delusion events are outside their comfort zone; aberrations.

In fact, engineers and managers are often trained to be blind to cascade events. Their training and work environment normally does not reward focusing on cascade events, but rather punishes it.

West Point is an extraordinarily controlled environment. Things run almost perfectly there; so much so that graduates often have problems adjusting to the ‘real’ Army they go into. But West Point also has over 200 years of experience training leaders and preparing soldiers for war. This accumulation of institutional knowledge is inculcated in cadets in a high-pressure cauldron of mental, physical, and emotional stress for four years.

West Point is an extraordinarily controlled environment. Things run almost perfectly there; so much so that graduates often have problems adjusting to the ‘real’ Army they go into. But West Point also has over 200 years of experience training leaders and preparing soldiers for war. This accumulation of institutional knowledge is inculcated in cadets in a high-pressure cauldron of mental, physical, and emotional stress for four years.

Of course, sometimes it doesn’t take, as you’d see in one of the events I cover in Shit Doesn’t Just Happen – The Gift of Failure. This book focuses on a number of colossal failures, including West Point’s most notorious graduate – Breverant Colonel George Armstrong Custer.

Special Operations soldiers train for war. War is called controlled chaos; an incessant series of cascade events. War might be considered the ultimate catastrophe and combat a final event. In order to prepare for this final event, Special Operations soldiers train for, plan for, and work in a chaotic environment every day.

Special Operations soldiers train for war. War is called controlled chaos; an incessant series of cascade events. War might be considered the ultimate catastrophe and combat a final event. In order to prepare for this final event, Special Operations soldiers train for, plan for, and work in a chaotic environment every day.

Mentally, the most difficult training I went through was Robin Sage, the final exercise in the Special Forces Qualification Course. Robin Sage is where a team of students is sent into isolation, and then infiltrates into the North Carolina countryside to conduct a guerilla warfare exercise. A critical component of Robin Sage is to put prospective Green Berets in lose-lose scenarios. This is a training scenario where there is no ‘right’ solution. Rigid minds are often unable to think creatively while under stress and lose-lose training quickly determines someone’s capabilities.

Thinking outside of the immediate situation is important in preparing for and averting catastrophes.

Do you remember in the Star Trek movie (Wrath of Khan) when Captain Kirk talks about being at Star Fleet Academy and being the only officer to have passed the Kobayashi Maru simulator program?

The basic problem and the opening of the movie was set up this way: A Star Fleet ship which the student commands is patrolling near the neutral zone. A distress call is received from a disabled Federation vessel inside the neutral zone. An enemy warship is approaching from the other side. It’s a vessel more powerful than the one the student commands. The choices seem obvious: ignore the distress call (which violates the law of space) or go to its aid (violating the neutral zone) and face almost certain destruction from the enemy vessel. As you can see, both choices are bad.

The basic problem and the opening of the movie was set up this way: A Star Fleet ship which the student commands is patrolling near the neutral zone. A distress call is received from a disabled Federation vessel inside the neutral zone. An enemy warship is approaching from the other side. It’s a vessel more powerful than the one the student commands. The choices seem obvious: ignore the distress call (which violates the law of space) or go to its aid (violating the neutral zone) and face almost certain destruction from the enemy vessel. As you can see, both choices are bad.

What Kirk did was sneak into the computer center the night before he was scheduled to go through the simulation and change the parameters so that he could successfully save the vessel without getting destroyed. Would you have thought of that? Was it cheating? If you ain’t cheating you ain’t trying. It’s not cheating when it succeeds.

What Kirk did was sneak into the computer center the night before he was scheduled to go through the simulation and change the parameters so that he could successfully save the vessel without getting destroyed. Would you have thought of that? Was it cheating? If you ain’t cheating you ain’t trying. It’s not cheating when it succeeds.

A key to lose-lose training is you get to see how someone reacts when they are wrong or fail. Lose-lose training is a good way to put people in a crisis. Frustration can often lead to anger, which can lead to failure or enlightenment.

If a catastrophe struck, whom would you want at your side helping you?

A doctor? Lawyer? Engineer? MBA? Teacher? While they all have special skills, I submit that the overwhelming choice might well be a US Special Forces Green Beret or, the best in the business – a British 22SAS. Someone trained in survival, medicine, weapons, tactics, communications, engineering, counter-terrorism, tactical and strategic intelligence, and with the capability to be a force multiplier.

A doctor? Lawyer? Engineer? MBA? Teacher? While they all have special skills, I submit that the overwhelming choice might well be a US Special Forces Green Beret or, the best in the business – a British 22SAS. Someone trained in survival, medicine, weapons, tactics, communications, engineering, counter-terrorism, tactical and strategic intelligence, and with the capability to be a force multiplier.

Most important, you want someone who has been handpicked, survived rigorous training, and has the positive mental outlook to not only survive, but thrive in chaos, and knows how to be part of a team. Green Berets have been called Masters of Chaos. They don’t manage. They lead.

The key to dealing with catastrophes is leadership, not management.

Often, in order to deal with a cascade event, leadership and courage are needed to go against a culture of complacency and fear. In every catastrophe, fear is a factor in at least one, if not more, cascade events. This fear runs the gamut from physical fear, to job security fear, to social fear, to physical fear. Few people want to be the ‘boy who cries wolf’ even when they see a pack of wolves. What’s even harder is when we’re the only one who sees the wolf in sheep’s clothing.

Often, in order to deal with a cascade event, leadership and courage are needed to go against a culture of complacency and fear. In every catastrophe, fear is a factor in at least one, if not more, cascade events. This fear runs the gamut from physical fear, to job security fear, to social fear, to physical fear. Few people want to be the ‘boy who cries wolf’ even when they see a pack of wolves. What’s even harder is when we’re the only one who sees the wolf in sheep’s clothing.

I’ve written Shit Doesn’t Just Happen: The Gift of Failure to help individuals and organizations avoid catastrophes, but I come at it from a different direction as a former Special Operations soldier. In the Special Forces (Green Berets) the key to our successful missions was the planning. The preparation. In isolation, we war-gamed as many possible catastrophe situations we could imagine for any upcoming mission and prepared as well as we could for them. In fact, we expected things to go wrong, a very different mindset from that of engineers and management.

I’ve written Shit Doesn’t Just Happen: The Gift of Failure to help individuals and organizations avoid catastrophes, but I come at it from a different direction as a former Special Operations soldier. In the Special Forces (Green Berets) the key to our successful missions was the planning. The preparation. In isolation, we war-gamed as many possible catastrophe situations we could imagine for any upcoming mission and prepared as well as we could for them. In fact, we expected things to go wrong, a very different mindset from that of engineers and management.