The Black Dahlia murder mystery is one of America’s—if not the world’s—biggest unsolved homicide investigations. On January 15, 1947 (75 years ago today) a pedestrian found 22-year-old Elizabeth Short’s body in Leimert Park’s district of West Los Angeles. Short was naked, bisected at the waist, viciously disfigured, and obviously posed in public display by her killer. Her case remains open despite more than 150 suspects surfaced and cleared—except for one—a main person of interest. Did this man really murder and mutilate a lady nicknamed The Black Dahlia?

The Black Dahlia murder mystery is one of America’s—if not the world’s—biggest unsolved homicide investigations. On January 15, 1947 (75 years ago today) a pedestrian found 22-year-old Elizabeth Short’s body in Leimert Park’s district of West Los Angeles. Short was naked, bisected at the waist, viciously disfigured, and obviously posed in public display by her killer. Her case remains open despite more than 150 suspects surfaced and cleared—except for one—a main person of interest. Did this man really murder and mutilate a lady nicknamed The Black Dahlia?

The Black Dahlia case wasn’t just a huge police investigation. It was a media frenzy as the public held a massive fascination with her body’s macabre and grotesque condition. The corpse was so shocking that I’m not going to publish photos in this post. If you’re curious, there are many Black Dahlia crime scene photos online.

Elizabeth (Betty or Beth) Short was born on July 29, 1924 near Boston Massachusetts. Her father disappeared after the October 1929 stock market crash and was believed to have committed suicide by jumping off a bridge into the Charles River. Beth Short’s mother raised her as a single working mother, however in 1942, the father turned up alive and living in Los Angeles.

Elizabeth (Betty or Beth) Short was born on July 29, 1924 near Boston Massachusetts. Her father disappeared after the October 1929 stock market crash and was believed to have committed suicide by jumping off a bridge into the Charles River. Beth Short’s mother raised her as a single working mother, however in 1942, the father turned up alive and living in Los Angeles.

Beth Short reacquainted with her father by moving to Los Angeles when she was 18. Their relationship turned rocky and she went o live on her own in 1945, surviving on waitress wages and with help from a few friends—mostly men. There was speculation Short was a prostitute/call girl but no evidence of that was found during her murder investigation.

She was more of a barfly/party girl and a little on the promiscuous side having numerous men-friends. One male suitor was an older gent, an Air Force pilot. He proposed marriage by letter but was accidentally killed in a plane crash before he could return to America and marry Beth Short.

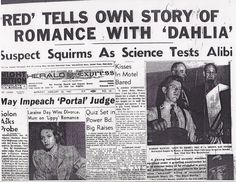

The last man to see Short alive—at least the last man police could identify—was a married travelling salesman Short secretly dated. Robert “Red” Manley liaised with Short in San Diego and dropped her off back in Los Angeles at the downtown Biltmore Hotel. This was on Thursday, January 9, 1947 and Short intended to meet her sister who was visiting from Boston.

They never connected. There are some accounts Short was seen using the lobby telephone at the Biltmore as well as unverified sightings of Short at the Crown Grill Cocktail Lounge about 3/8 mile northwest of the Biltmore. Here Short’s trail went cold, and there was a week gap until her body was found.

They never connected. There are some accounts Short was seen using the lobby telephone at the Biltmore as well as unverified sightings of Short at the Crown Grill Cocktail Lounge about 3/8 mile northwest of the Biltmore. Here Short’s trail went cold, and there was a week gap until her body was found.

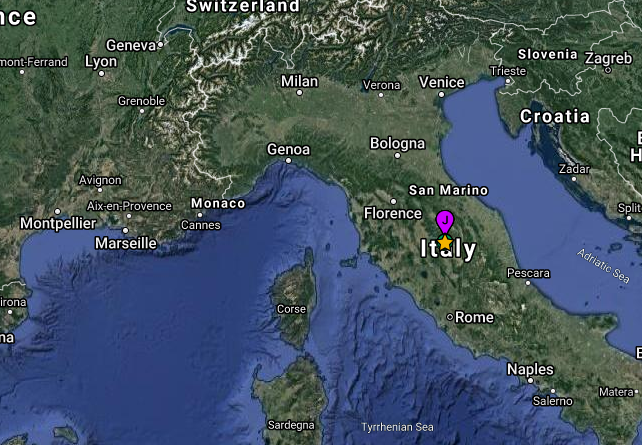

At 10:00 am on Wednesday, January 15, Betty Bersinger was walking with her three-year-old daughter in an undeveloped area of Leimert Park midway between Coliseum Street and West 39th Street (GPS Coordinates 34.016 N and 118.333 W). Bersinger saw what she believed to be two parts of a department store mannequin lying just to the side of the roadway in a very exposed position. On closer inspection, Bersinger realized the ghostly-white corpse was human. She rushed to a nearby house and phoned the police.

As two detectives arrived at the crime scene, so did passerbys and reporters which soon grew to a crowd of onlookers and a throng of media. This was before the days of controlled CSI examination with yellow barrier tape and uniformed guards keeping the public and press from observing and releasing key-fact information such as the body condition.

Los Angeles pathologist and County Coroner Frederick Newbarr autopsied Elizabeth Short on January 16, 1947. His report described the body as a white female, early 20s, 5’ 5” tall, 115 lbs. with light blue eyes, dark brown hair, and badly decayed teeth. These are the highlights of Short’s autopsy report:

- The body was completely devoid of blood.

- There was minimal blood about the scene, amounting to a few drops.

- The corpse had been washed with a mineral solvent, possibly gasoline.

- The upper torso was horizontally severed from the lower abdomen and legs.

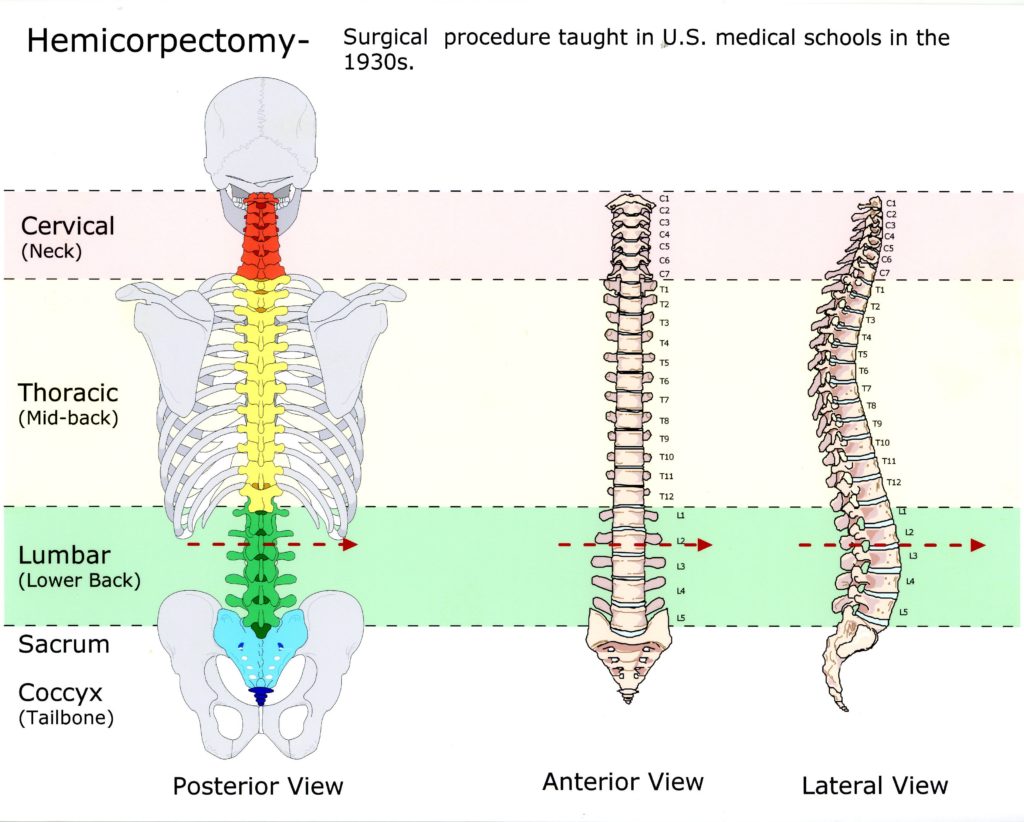

- The anatomical point of severance was between the 2nd and 3rd lumbar vertebrae.

- The upper torso organs were present and attached.

- The intestines had been removed and coiled up underneath the buttocks.

- There were injuries to the scalp and skull consistent with blunt force trauma.

- Both corners of the mouth were incised and elongated approximately 4 inches.

- The mouth incisions were made antemortem (before death), evident by ecchymosis or bruising to the wound edges.

- Numerous postmortem (after death) cuts were made in random order about her torso, pelvis, and legs, evident by a lack of ecchymosis to the wound edges.

- Antemortem ligature marks were evident on the wrists, ankles, and neck indicating she had been bound or restrained before death.

- The anal orifice was fixed in dilated measurement of 1 and ¾ inches.

- No semen or foreign trace evidence indicating an assailant was found.

- General body condition indicated that death occurred approximately ten hours before body discovery making the death time somewhere over the night of January 14-15.

- Official cause of death was shock from cerebral injuries and blood loss from the mouth.

The coroner, with the help of the FBI, identified Short’s body through fingerprints. Short had been previously arrested and processed in Santa Barbara for underage drinking (Yes, back in the 40s a minor in alcohol possession was a big deal). This opened the investigative trail to track Short’s whereabouts and develop leads.

In one of the lowest and most disgusting points in the entire history of journalism, reporters from William Randolph Hearst’s Los Angeles Examiner intercepted the identification information—thought to be through a police source—and telephoned Short’s mother in Boston before the police could make an in-person notification of death. The reporters roused the mother under the guise that Beth had won a beauty to which they wanted to run a feature story. Through this, they gained a lot of personal information which they fed to the drooling public.

In one of the lowest and most disgusting points in the entire history of journalism, reporters from William Randolph Hearst’s Los Angeles Examiner intercepted the identification information—thought to be through a police source—and telephoned Short’s mother in Boston before the police could make an in-person notification of death. The reporters roused the mother under the guise that Beth had won a beauty to which they wanted to run a feature story. Through this, they gained a lot of personal information which they fed to the drooling public.

The killer was watching this all. On January 21, an unknown male phoned the Examiner’s editor congratulating them on their coverage, including publishing the crime scene photos of Short’s nude and butchered body. The caller told the editor to, “Expect some souvenirs from Beth Short in the mail”.

On January 24, the Examiner editor received a package with Short’s birth certificate, personal papers, and address book. A cut and pasted note gave clues to where Short’s shoes and purse were hidden. These were found and verifies as legitimate.

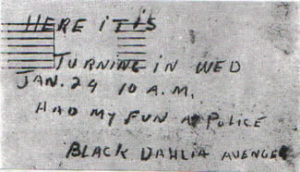

The Examiner got a hand-written note on January 26, dated January 24. This time the writer who claimed to be the Black Dahlia Avenger stated he would turn himself in, arranging a time and a place for coverage. It didn’t happen. The last contact with the killer was another cut and pasted letter on January 29 which read, “Have changed my mind. You would not give me a square deal. Dahlia killing was justified.”

The Examiner got a hand-written note on January 26, dated January 24. This time the writer who claimed to be the Black Dahlia Avenger stated he would turn himself in, arranging a time and a place for coverage. It didn’t happen. The last contact with the killer was another cut and pasted letter on January 29 which read, “Have changed my mind. You would not give me a square deal. Dahlia killing was justified.”

In 12 days, from the body discovery to the killer’s last contact, the Black Dahlia story went from unknown to front-page headlines that lasted months. Where did the Black Dahlia name come from to immortalize a poor and innocent victim like Elizabeth Short? No one really knows, but there are two schools of thought.

One is that the news media simply made it up to further sensationalize an already over-the-top story. The other is possibly from drug store staff where Short shopped. Allegedly, Short always dressed in black and wore a flower in her hair. Combined with her striking white skin, she made a spectacle which the staff called The Black Dahlia, possibly a word-play on a 1946 movie titled The Blue Dahlia. It’s possible intrepid reporters picked up the nickname and used it to sell more papers.

LAPD detectives focused on Beth Short’s trail and her male acquaintances, especially those having recent contact with her before her death. Red Manley was eliminated after two polygraphs and an air-tight, sworn alibi. Others took a lot of effort by a lot of officers to satisfy them the person they were interested in was not responsible.

LAPD detectives focused on Beth Short’s trail and her male acquaintances, especially those having recent contact with her before her death. Red Manley was eliminated after two polygraphs and an air-tight, sworn alibi. Others took a lot of effort by a lot of officers to satisfy them the person they were interested in was not responsible.

And the LAPD detectives focused on two absolutely unique aspects of the Black Dahlia crime scene and autopsy findings which, in this day and age, would have been critical hold-back evidence known only to the investigators and the killer—nor publically splattered and speculated on throughout every western media outlet.

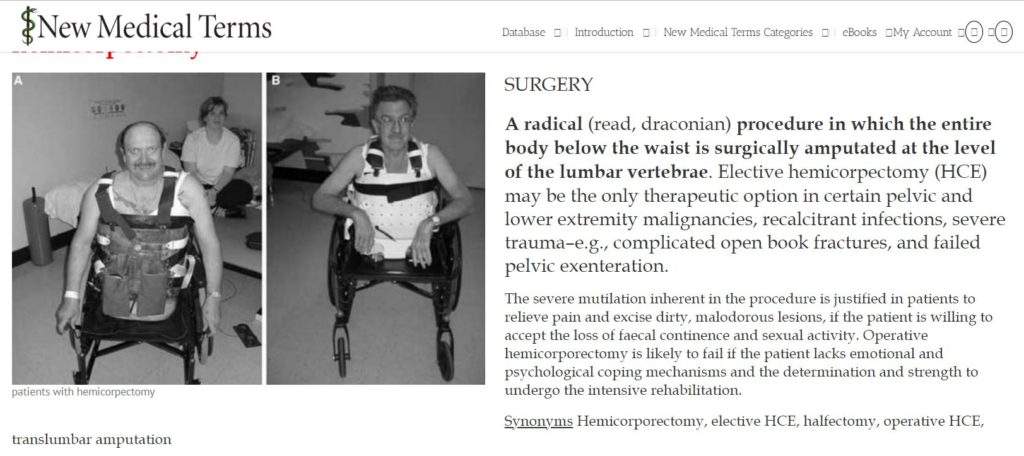

First was the method Beth Short had been cut in half with. The pathologist/coroner, Dr. Frederick Newbarr, later testified at Short’s inquest that the severance was a surgical procedure that only could have been done by a highly-trained surgeon with the proper surgical equipment. Dr. Newbarr stated—under oath and on the record—the severance was a medical procedure developed in the 1930s and termed a hemicorporectomy.

A hemicorporectomy was a last-ditch effort to save a person’s life when the entire pelvic system was failing. To not remove the pelvis, buttock, and leg assembly (including the lower GI tract) would have meant certain death so surgeons would resort to, literally, cutting a person in half and discarding the lower region.

This radical surgical procedure left the patient alive and confined to a walker-like device for mobility and a colostomy bag for capturing waste exiting the stomach at the duodenum. The only place in the spine a hemicorporectomy could be achieved was between the 2nd and 3rd lumbar vertebrae.

In Dr. Newbarr’s words, “Whoever did this surgical procedure (to Elizabeth Short’s body) was a very fine surgeon.”

The second unique aspect of the crime scene findings was Short’s body positioning. From the onset, both press and police emphasized the body wasn’t just dumped at the discovery point—it was carefully and craftily posed for some definite purpose. There was no attempt to hide the corpse. No, it was the opposite. The killer wanted it found and publically published.

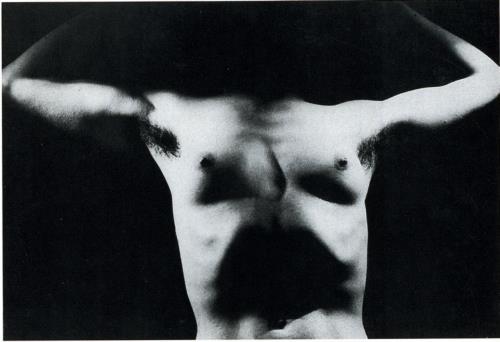

If you’re strong-stomached enough to view the crime scene photos, you’ll see Short’s remains lying supine (on her back) with her arms extended straight out from her shoulders with her elbows bent 90-degrees upward to make a football goalpost-like frame over her head. You’ll see Short’s lower segment offset to the right of her torso and her right hip in line with her left side. Also, you’ll see the torso/hip offset distance to be the same as the gap between her upper and lower segments. Then, you’ll note Short’s legs are positioned wide open in a 90-degree separation or a 45-degree split from the midline of her vagina.

There isn’t an experienced cop, coroner, or criminologist who wouldn’t see meaning in this crime scene. It’s painfully obvious the killer positioned Short’s body to send a message. But what bizarre message by what bizarre surgeon-killer could that be?

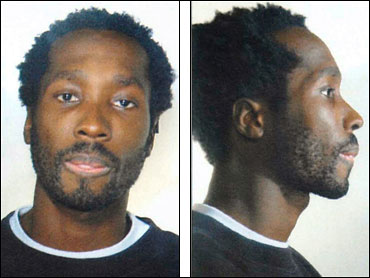

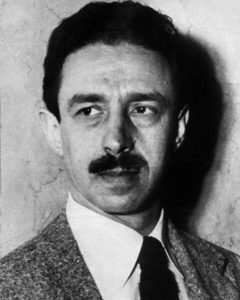

It seems the LAPD detectives had a person of interest in their sights early in the Black Dahlia murder investigation. The LAPD file is still open and ongoing, although cold, so they control information as they should. What’s known about their interest in Dr. George Hill Hodel Jr. is officially confidential but quite well-known in the internet, book, and movie world.

It seems the LAPD detectives had a person of interest in their sights early in the Black Dahlia murder investigation. The LAPD file is still open and ongoing, although cold, so they control information as they should. What’s known about their interest in Dr. George Hill Hodel Jr. is officially confidential but quite well-known in the internet, book, and movie world.

Dr. George Hodel was surgically trained in the 1930s. He was familiar with the hemicorporectomy procedure, and he was familiar with sexual deviancy. Hodel was charged with incest on his 14-year-old daughter who, by the way, knew Elizabeth Short’s sister. There was one degree of separation between Surgeon Hodel and Victim Short including the several-block distance from the Biltmore Hotel and the Crown Gate Cocktail Lounge to where Hodel’s clinic operated.

Although George Hodel was a trained surgeon, he made money though his clinic specializing in treating venereal disease. At the time, the forties, VD was rampant through sexually-promiscuous people and it was something held in shame and confidence. Was Elizabeth Short a VD patient of Dr. Hodel’s as well as being a through-family acquaintance?

The detectives thought so. They thoroughly investigated Hotel including bugging his home where they heard this:

“Supposin’ I did kill the Black Dahlia. They couldn’t prove it now. They can’t talk to my secretary anymore because she’s dead. They though there was something fishy. Anyway, now they may have figured it out. Killed her. Maybe I did kill my secretary.”

Those statements were suspicious enough to make detectives look into the death of Ruth Spalding. She was Dr. Hodel’s clinic assistant who died of a mysterious drug overdose shortly after the Dahlia case happened. Speculation by detectives is Spalding recognized Elizabeth Short as a patient, knew Hodel’s surgical experience, and put 2&2 together.

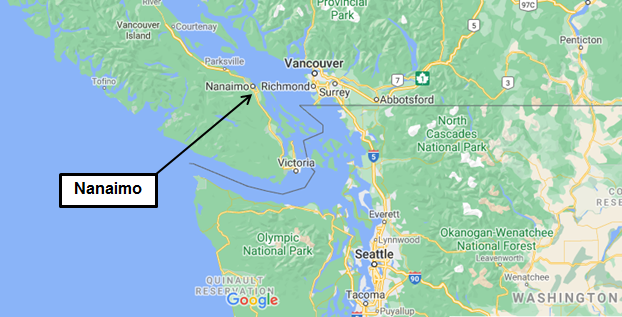

The detectives, and possibly Ruth Spalding, weren’t the only ones who suspected Dr. George Hodel was the Black Dahlia’s killer. In 1950, when the heat was on George Hodel and the Dahlia recording was intercepted, Hodel moved to the Philippines where died in 1999. Hodel remains an LAPD person of interest in the Dahlia case.

Someone else also considers Dr. George Hill Hodel as the Dahlia killer. That’s his son. Steve Hodel who, coincidentally, is a retired LAPD homicide detective. It wasn’t until he retired that Steve Hodel put 2&2 together when he reviewed property from his father’s estate and found highly-suspicious material linking his father as the Dahlia killer.

Someone else also considers Dr. George Hill Hodel as the Dahlia killer. That’s his son. Steve Hodel who, coincidentally, is a retired LAPD homicide detective. It wasn’t until he retired that Steve Hodel put 2&2 together when he reviewed property from his father’s estate and found highly-suspicious material linking his father as the Dahlia killer.

One was photographs of a young woman similar to Elizabeth Short. Two was handwriting samples similar to the Examiner hand-written note. Then, the fact his father worked so close to the scene where Short was last seen and, in all probability knew and possibly treated Short. And then there was the coincidence Short’s body was posed close—very close—to Hodel’s estranged wife’s house.

Certainly Dr. George Hodel had the means and opportunity to be the Balck Dahlia killer. Motive isn’t an included element in any murder trial. There’s no burden for the prosecution to prove motive in any case—corporal or capital—but proving motive tips the scale in persuading a jury to convict beyond all reasonable doubt.

Assuming George Hodel—who had the surgical means to perform a hemicorporectomy and was lurking in the vicinity when Beth Short disappeared along with his history of sexual deviance and a hint of homicide—was the Black Dahlia killer, the question is why?

His son, Steve Hodel, supplies it. Art work. George Hodel had a close friend named Man Ray who was a 1930s-1940s surrealist artist—a prominent who worked with greats like Salvador Dali.

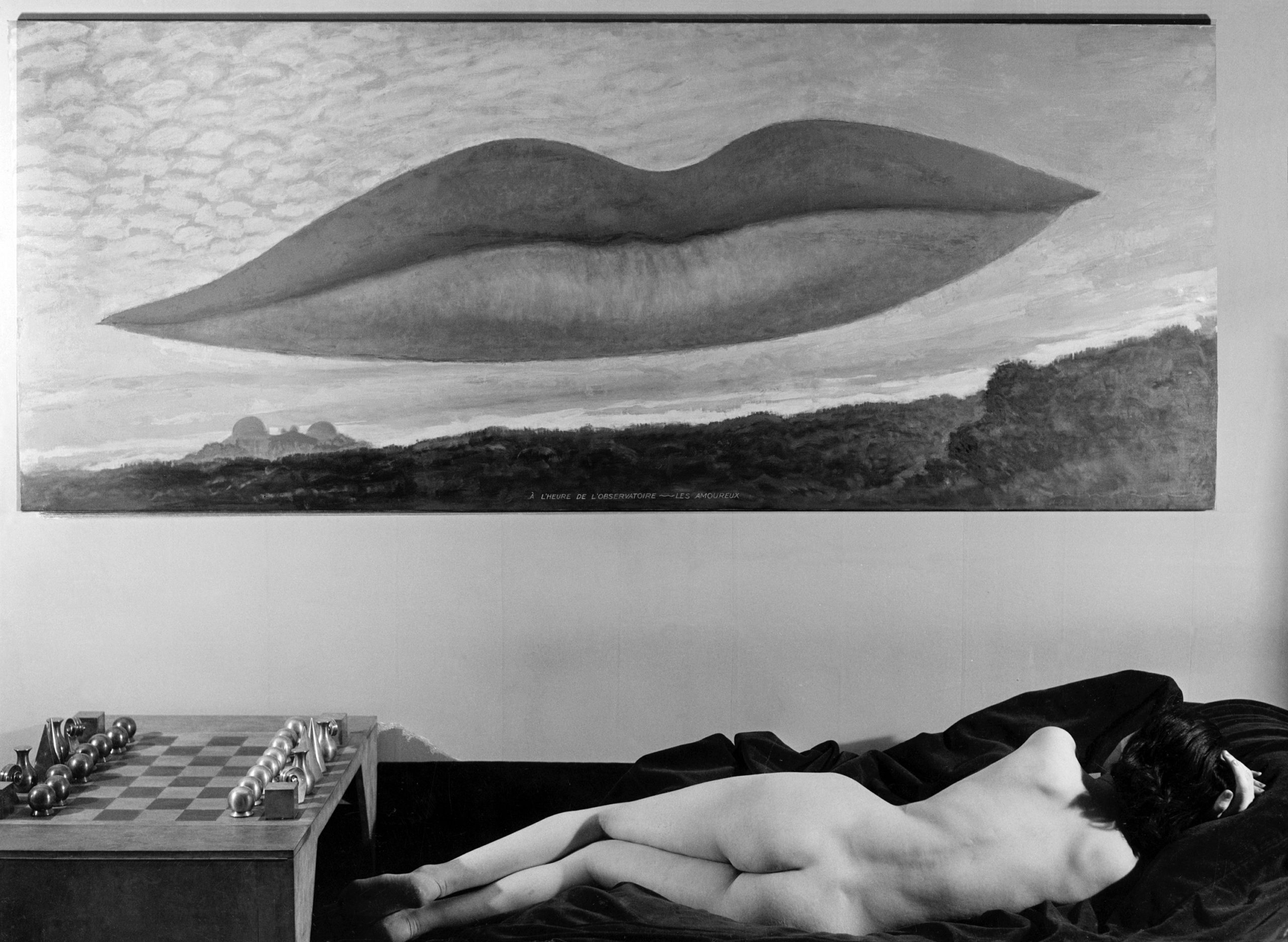

Steve Hodel identifies two hard-to-ignore similarities between Man Ray’s art and the Black Dahlia’s posing. Ray’s 1936 piece Les Amoureux shows an elongated woman’s mouth with slit-like extensions and a corpse-like figure below and admiring it. Ray’s 1934 Minotaur shows a naked woman’s torso with the goalpost-like arm-posing.

Something I can’t ignore is the mathematical connection between Man Ray’s surrealist art and the Black Dahlia’s pose. Elizabeth Short’s arms were 90-degrees from her shoulders to her forearms, and her forearms were 90-degrees upward from them. Her torso was 90-degree offset, equidistant from the separation of her lower section. And her legs were a 45/90-degree posing from her pubis.

This posing was no accident. It was no coincidence. It was a purposeful display of artistic impression.

In my death investigation experience, I’ve never seen anything close to the Black Dahlia case. I’ve never seen intentional grotesque mutilation like this, and that’s why I haven’t posted pictures. But, I do see hard-to-deny facts.

Two principles guide homicide investigations. First—the more bizarre the case, the closer the answer is to home. Second—Occam’s razor. The Principle of Parsimony. When faced with multiple explanations, the simplest answer is usually the right answer.

On the balance of probabilities—with no better solution—I believe Dr. George Hill Hodel really murdered and mutilated the Black Dahlia.