The psychology of effective police interrogation is complex. Today’s interrogators train in communication, human behavioural science, and legal procedures. They hone their skills through years of practice. But regardless of how smooth-talking a detective may be, the secret to success in securing admissible confessions will always lie in being a good listener, mentally manipulating the suspect, and using common sense.

The psychology of effective police interrogation is complex. Today’s interrogators train in communication, human behavioural science, and legal procedures. They hone their skills through years of practice. But regardless of how smooth-talking a detective may be, the secret to success in securing admissible confessions will always lie in being a good listener, mentally manipulating the suspect, and using common sense.

In my years as a homicide investigator and dealing with suspects, I’ve worked with excellent interrogators. RCMP Polygraphist Don Adam was one of the best. Don was a natural in getting suspects to talk. I was fortunate to learn from guys like Don in mastering techniques that got confessions that’d stick in court. There’s a point where natural talent and learned techniques intertwine. That produces a good interrogator who produces good evidence.

In my years as a homicide investigator and dealing with suspects, I’ve worked with excellent interrogators. RCMP Polygraphist Don Adam was one of the best. Don was a natural in getting suspects to talk. I was fortunate to learn from guys like Don in mastering techniques that got confessions that’d stick in court. There’s a point where natural talent and learned techniques intertwine. That produces a good interrogator who produces good evidence.

Courts in the civilized world have a basic criteria for admitting confessions from accused persons as evidence. This pertains to statements made to persons in authority, ie – cops:

- Statements must be voluntary. Suspects can’t be threatened in any way or promised a favor in return for talking.

- Suspects must be aware of their legal rights and waive an opportunity to exercise them.

- Their rights are to remain silent and to consult a lawyer, if they choose.

The reasons for these strict rules are to avoid the chance of false confessions being used to convict people and ensuring an ethical theater in law enforcement. Interrogations are usually done in an accusatory, guilt presumptive process and not in an objective environment. So they begin with a definite bias – not like a court proceeding which operates with a presumption of innocence.

The reasons for these strict rules are to avoid the chance of false confessions being used to convict people and ensuring an ethical theater in law enforcement. Interrogations are usually done in an accusatory, guilt presumptive process and not in an objective environment. So they begin with a definite bias – not like a court proceeding which operates with a presumption of innocence.

It’s also vitally important that confessions to crimes be corroborated in some way that verifies their truthfulness. Corroboration means backing up the confession with some form of evidence that proves the subject is being truthful and not elicited into making a false confession. Examples of corroboration are turning over a murder weapon, directing investigators to the location of a hidden body or divulging some key fact(s) known only to the perpetrator and the investigators. Corroboration is a must in verifying truthfulness and avoiding the chance of false confessions being used to convict an accused.

I’ve seen a lot of unscientific techniques applied in interrogations. The oldest one is the good cop – bad cop thing. Sometimes it works. Sometimes it backfires. Buddy-buddying the suspect only succeeds if there’s common ground. Minimization – Maximization. Cat & mouse. Outright deception to a subject is dangerous. If the interrogator is caught lying – it’s pretty much over. Torture – mental or physical – is completely unacceptable and would probably end with the cop in jail.

So what’s the best interrogation procedure?

Well, it’s been around for a long time since an American polygraphist by the name of John E. Reid figured out a 9 Step formula of psychological manipulation which is known as the Reid Technique.

Well, it’s been around for a long time since an American polygraphist by the name of John E. Reid figured out a 9 Step formula of psychological manipulation which is known as the Reid Technique.

The basic premise of interrogation is to manipulate the suspect into talking and then listen to what they’re saying. Once they start talking, it’s hard for them to stop. Once they start telling the truth, it’s harder to continue lying.

In the Reid Technique, interrogation is an accusatory process where the interrogator opens by telling the suspect that there’s no doubt about their guilt. The interrogator delivers a monologue rather than a question and answer format and the composure is understanding, patient, and non-demeaning. The goal is making the suspect progressively more and more comfortable with acknowledging the truth about what they’ve done. This is accomplished by the interrogator first imagining and then offering the subject various psychological constructs as justification for their behavior.

For example, an admission of guilt might be prompted by the question, “Did you plan this out or did it just happen on the spur of the moment?” This technique uses a loaded question that contains the unspoken, implicit assumption of guilt. The idea is that the suspect must catch the hidden assumption and contest it to avoid the trap.

For example, an admission of guilt might be prompted by the question, “Did you plan this out or did it just happen on the spur of the moment?” This technique uses a loaded question that contains the unspoken, implicit assumption of guilt. The idea is that the suspect must catch the hidden assumption and contest it to avoid the trap.

But the psychological manipulation begins before the interrogator even opens his mouth, though.

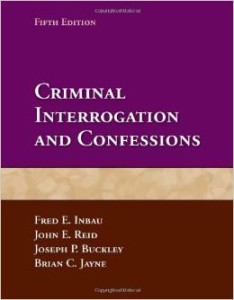

The physical layout of an interrogation room is designed to maximize a suspect’s discomfort and sense of powerlessness from the moment they step inside. The classic interrogation manual Criminal Interrogation and Confessions, which was co-written by John Reid, recommends a small, soundproof room with only two or three chairs, a desk, and nothing on the walls. This creates a sense of exposure, unfamiliarity, and isolation. It heightens the suspect’s “get me out of here” sensation throughout the interrogation.

The manual also suggests that the suspect should be seated in an uncomfortable chair, out of reach of any controls like light switches or thermostats, furthering his discomfort and setting up a feeling of dependence. A one-way mirror and/or closed circuit TV are great additions to the room, because they increases the suspect’s anxiety and allows other interrogators to watch the process and help the principle interrogator figure out which techniques are working and which aren’t.

The manual also suggests that the suspect should be seated in an uncomfortable chair, out of reach of any controls like light switches or thermostats, furthering his discomfort and setting up a feeling of dependence. A one-way mirror and/or closed circuit TV are great additions to the room, because they increases the suspect’s anxiety and allows other interrogators to watch the process and help the principle interrogator figure out which techniques are working and which aren’t.

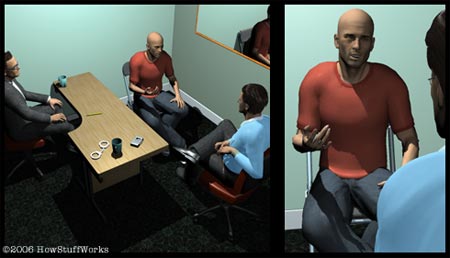

Before the 9 Steps of the Reid Technique begin, there’s an initial interview to determine guilt or innocence. During this time, the interrogator attempts to develop a rapport with the suspect, using casual conversation to create a non-threatening atmosphere. People tend to like and trust people who are like them, so the interrogator may claim to share some of the suspect’s interests or beliefs. If the suspect starts talking to the interrogator about harmless things, it becomes harder to stop talking or start lying later when the discussion turns to the crime.

During this initial conversation, the interrogator observes the suspect’s reactions, both verbal and non-verbal, to establish a baseline reaction before the real stress begins. The interrogator will later use this baseline as a control or comparison point. One method of creating a baseline involves asking questions that cause the suspect to access different parts of their brain.

During this initial conversation, the interrogator observes the suspect’s reactions, both verbal and non-verbal, to establish a baseline reaction before the real stress begins. The interrogator will later use this baseline as a control or comparison point. One method of creating a baseline involves asking questions that cause the suspect to access different parts of their brain.

Non-threatening questions are asked that require memory (simple recall) and questions that require thinking (creativity). When the suspect is remembering something, their eyes often move to the right. This is an outward manifestation of their brain activating the memory center. When they’re thinking about something, the eyes will move upward or to the left, reflecting activation of the cognitive center. A trained, experienced interrogator makes a mental note of the suspect’s eye activity.

The next step is turning to the question at hand.

The interrogator asks basic questions about the crime and compares the suspect’s reactions to the baseline. This is quite an accurate determination if the suspect is truthful or deceptive. For example, if the interrogator asks the suspect where they were the night of the crime and they answer truthfully, they’ll honestly be remembering so their eyes will move to the right. If they’re concocting an alibi, they’re thinking, so the eyes will go up or to the left. If the interrogator determines that the suspect’s reactions indicate deception and all other evidence points to guilt, then a structured interrogation of the suspect begins.

The interrogator asks basic questions about the crime and compares the suspect’s reactions to the baseline. This is quite an accurate determination if the suspect is truthful or deceptive. For example, if the interrogator asks the suspect where they were the night of the crime and they answer truthfully, they’ll honestly be remembering so their eyes will move to the right. If they’re concocting an alibi, they’re thinking, so the eyes will go up or to the left. If the interrogator determines that the suspect’s reactions indicate deception and all other evidence points to guilt, then a structured interrogation of the suspect begins.

The Reid Technique lays out a proven blueprint of 9 Steps or issues guiding an interrogation. Many of these steps overlap and there is no such thing as a “typical” interrogation. Here’s how it should go.

1.Confrontation

The interrogator presents the facts of the case and informs the suspect of the evidence against them implying in a confident manner that the suspect is involved in the crime. The suspect’s stress level increases and the interrogator may move around the room, invading the suspect’s personal space to increase the discomfort. If the suspect starts fidgeting, licking lips, and/or grooming themselves (running his hand through their hair, for instance), the interrogator notes these as deception indicators confirming their on the right track.

The interrogator presents the facts of the case and informs the suspect of the evidence against them implying in a confident manner that the suspect is involved in the crime. The suspect’s stress level increases and the interrogator may move around the room, invading the suspect’s personal space to increase the discomfort. If the suspect starts fidgeting, licking lips, and/or grooming themselves (running his hand through their hair, for instance), the interrogator notes these as deception indicators confirming their on the right track.

2. Theme Development

The interrogator creates a story about why the suspect committed the crime. Theme development is about looking through the eyes of the suspect to figure out why they did it. The interrogator lays out a theme or a story that the suspect can latch on to in order to either excuse or justify their part in the crime and the interrogator observes the suspect to see if they’re buying the theme. Are they paying closer attention than before? Nodding their head? If so, the interrogator will continue developing that theme; if not, they’ll pick a new theme and start over. Theme development is in the background throughout the interrogation. When developing themes, the interrogator speaks in a soft, soothing voice to appear non-threatening and to lull the suspect into a false sense of security.

3. Stopping Denials

Letting the suspect deny their guilt will increase their confidence, so the interrogator tries to interrupt all denials, sometimes telling the suspect it’ll be their turn to talk in a moment, but right now, they need to listen. From the start of the interrogation, the interrogator watches for denials and stops the suspect before they can voice them. In addition to keeping the suspect’s confidence low, stopping denials also helps quiet the suspect so they don’t have a chance to ask for a lawyer. If there are no denials during theme development, the interrogator takes this as a positive indicator of guilt. If initial attempts at denial slow down or stop during theme development, the interrogator knows they’ve found a good theme and that the suspect is getting closer to confessing.

Letting the suspect deny their guilt will increase their confidence, so the interrogator tries to interrupt all denials, sometimes telling the suspect it’ll be their turn to talk in a moment, but right now, they need to listen. From the start of the interrogation, the interrogator watches for denials and stops the suspect before they can voice them. In addition to keeping the suspect’s confidence low, stopping denials also helps quiet the suspect so they don’t have a chance to ask for a lawyer. If there are no denials during theme development, the interrogator takes this as a positive indicator of guilt. If initial attempts at denial slow down or stop during theme development, the interrogator knows they’ve found a good theme and that the suspect is getting closer to confessing.

4. Overcoming Objections

Once the interrogator has fully developed a theme that the suspect relates to, the suspect may offer logic-based objections as opposed to simple denials, like “I could never rape somebody — my sister was raped and I saw how much pain it caused. I would never do that to someone.” The interrogator handles these differently than denials because these objections can give information to turn around and use against the suspect. The interrogator might say something like, “See, that’s good, you’re telling me you would never plan this, that it was out of your control. You care about women like your sister — it was just a one-time mistake, not a recurring thing.” If the interrogator does his job right, an objection ends up looking more like an admission of guilt.

5. Getting Suspect’s Attention

At this point, the suspect should be frustrated and unsure of themselves. They may be looking for someone to help him escape the situation. The interrogator tries to capitalize on that insecurity by pretending to be the suspect’s ally. They’ll try to appear even more sincere in their continued theme development and may get physically closer to the suspect, making it harder for the suspect to detach from the situation. The interrogator may offer physical gestures of camaraderie and concern, such as touching the suspect’s shoulder or patting his back.

At this point, the suspect should be frustrated and unsure of themselves. They may be looking for someone to help him escape the situation. The interrogator tries to capitalize on that insecurity by pretending to be the suspect’s ally. They’ll try to appear even more sincere in their continued theme development and may get physically closer to the suspect, making it harder for the suspect to detach from the situation. The interrogator may offer physical gestures of camaraderie and concern, such as touching the suspect’s shoulder or patting his back.

6. Suspect Looses Resolve

If the suspect’s body language indicates surrender – head in his hands, elbows on knees, shoulders hunched — the interrogator seizes the opportunity to start leading the suspect into confession. It transitions from theme development to motive alternatives that force the suspect to choose a reason why they committed the crime. At this stage, the interrogator makes every effort to establish eye contact with the suspect to increase the suspect’s stress level and desire to escape. If, at this point, the suspect cries, the interrogator knows it’s a positive indicator of guilt.

7. Alternatives

The interrogator offers two contrasting motives for some aspect of the crime, sometimes beginning with a minor aspect so it’s less threatening to the suspect. One alternative is socially acceptable (“It was a crime of passion”), and the other is morally repugnant (“You killed her for the money”). The interrogator builds up the contrast between the two alternatives until the suspect gives an indicator of choosing one, like a nod of the head or increased signs of surrender. Then, the interrogator speeds things up.

The interrogator offers two contrasting motives for some aspect of the crime, sometimes beginning with a minor aspect so it’s less threatening to the suspect. One alternative is socially acceptable (“It was a crime of passion”), and the other is morally repugnant (“You killed her for the money”). The interrogator builds up the contrast between the two alternatives until the suspect gives an indicator of choosing one, like a nod of the head or increased signs of surrender. Then, the interrogator speeds things up.

8. Bringing Suspect Into Conversation

Once the suspect chooses an alternative, the confession has begun. The interrogator encourages the suspect to talk about the crime and might arrange for a second interrogator in room to increase the suspect’s stress level and his desire to give up and tell the truth. A new person into the room also forces the suspect to reassert his socially acceptable reason for the crime, reinforcing the idea that the confession is a done deal.

9. The Confession

The final stage of an interrogation is all about getting a truthful confession that will be admitted as evidence at trial. Virtually all interrogations today are recorded on audio/visual and transcripts are developed. There are further evidentiary tools used during confession besides words. Having the suspect draw maps or sketches of the scene, confess to secondary parties, write letters of apology, and returning the suspect back to the scene and re-enact the crime are commonly used. It’s vitally important to back-up the truthfulness of the confession with independent, corroborating evidence such as disclosing ‘key facts’ of the crime which would only be known to the perpetrator and investigators, or turning over critically implicating evidence like the murder weapon.

The final stage of an interrogation is all about getting a truthful confession that will be admitted as evidence at trial. Virtually all interrogations today are recorded on audio/visual and transcripts are developed. There are further evidentiary tools used during confession besides words. Having the suspect draw maps or sketches of the scene, confess to secondary parties, write letters of apology, and returning the suspect back to the scene and re-enact the crime are commonly used. It’s vitally important to back-up the truthfulness of the confession with independent, corroborating evidence such as disclosing ‘key facts’ of the crime which would only be known to the perpetrator and investigators, or turning over critically implicating evidence like the murder weapon.

These steps represent some of the psychological techniques that interrogators use to get confessions from suspects, but real interrogations don’t always follow the textbook.

These steps represent some of the psychological techniques that interrogators use to get confessions from suspects, but real interrogations don’t always follow the textbook.

Critics of the Reid Technique claim that it too easily produces false confessions, especially with young people. The use of the Reid Technique on youths is prohibited in several European countries because of the incidence of false confessions and wrongful convictions that result.

Critics of the Reid Technique claim that it too easily produces false confessions, especially with young people. The use of the Reid Technique on youths is prohibited in several European countries because of the incidence of false confessions and wrongful convictions that result.

Although it’s widely used and accepted in the USA, the Canadian courts are careful in admissibility of confessions extracted in this method, ruling that “stripped to its bare essentials, the Reid Technique is a guilt-presumptive, confrontational, psychologically manipulative procedure whose purpose is to extract a confession, not necessarily a truthful confession.” John E. Reid and Associates, the Chicago firm that holds rights to the technique and its teachings maintains that “it’s not the technique that causes false or coerced confessions, but police detectives who apply improper interrogation procedures.”

I’ve seen the Reid Technique put into practice many times with great success.

The best example of a textbook Reid Technique interrogation is the case of Colonel Russell Williams, a Canadian Air Force commander who confessed to two sex-murders. The interrogator was Detective Sergeant Jim Smyth of the Ontario Provincial Police’s Behavioral Science Unit. The skill employed by Det. Sgt. Smyth is nothing short of magic. Smyth made sure this confession’s truthfulness was verified.

The best example of a textbook Reid Technique interrogation is the case of Colonel Russell Williams, a Canadian Air Force commander who confessed to two sex-murders. The interrogator was Detective Sergeant Jim Smyth of the Ontario Provincial Police’s Behavioral Science Unit. The skill employed by Det. Sgt. Smyth is nothing short of magic. Smyth made sure this confession’s truthfulness was verified.