Joseph Wambaugh is crime writing’s master of cop & crook characters. Unlike many crime writers, Joe Wambaugh policed in the Los Angeles trenches. He’s worked with guys like Roscoe Rules, a fictional yet true-to-life rogue in The Choir Boys whose behavior was delightfully over-the-top. Wambaugh also served with psychologically-wounded real-life officers like Karl Hettinger portrayed in The Onion Field as a PTSD victim sadly spirally down after his partner’s on-duty execution. And, after 50 years in the police and crime writing business, Joseph Wambaugh knows his characters and remains down-to-earth. I’m honored to share the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) Quarterly magazine’s recent interview with crime writing’s master.

Joseph Wambaugh is crime writing’s master of cop & crook characters. Unlike many crime writers, Joe Wambaugh policed in the Los Angeles trenches. He’s worked with guys like Roscoe Rules, a fictional yet true-to-life rogue in The Choir Boys whose behavior was delightfully over-the-top. Wambaugh also served with psychologically-wounded real-life officers like Karl Hettinger portrayed in The Onion Field as a PTSD victim sadly spirally down after his partner’s on-duty execution. And, after 50 years in the police and crime writing business, Joseph Wambaugh knows his characters and remains down-to-earth. I’m honored to share the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) Quarterly magazine’s recent interview with crime writing’s master.

* * *

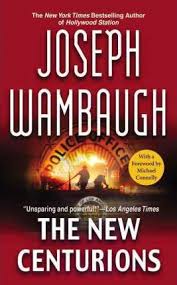

In 1971, Little, Brown & Company published a novel with a catchy title, The New Centurions. It was the first book from a young writer who described his profession in a way never been done before. The author was a homicide detective with the Los Angeles Police Department and the book was an unorthodox look at policing—full of colorful characters tossed together in a zany, chaotic world of life and death. Joseph Wambaugh was describing policing in the City of Los Angeles, but it might as well have been any city. The New Centurions was a runaway bestseller.

In 1971, Little, Brown & Company published a novel with a catchy title, The New Centurions. It was the first book from a young writer who described his profession in a way never been done before. The author was a homicide detective with the Los Angeles Police Department and the book was an unorthodox look at policing—full of colorful characters tossed together in a zany, chaotic world of life and death. Joseph Wambaugh was describing policing in the City of Los Angeles, but it might as well have been any city. The New Centurions was a runaway bestseller.

Joe Wambaugh went on to write 15 more novels and 5 non-fiction books. He wrote TV scripts, contributed to movies and television shows, and became a household name in police and literary circles. Fame forced him to leave policing and propelled him onto the author’s circuit in countries around the world. He made appearances on countless TV shows, including The Tonight Show with Johnny Carson.

Wambaugh’s fame continues to this day. His books continue to sell, phrases he coined are commonly used in policing and—most of all—he left a profound mark on the police profession. Joseph Wambaugh understood cops. He also recognized the emotional toll of “the job” on police officers, long before Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) was a diagnosed condition.

Joe Wambaugh also exposed the disparities in society through his examination of topics as diverse as dog shows and prostitution, describing the opulence and hypocrisy of some, as a counterpoint to the pathetic underbelly of society. Wambaugh described the job of a police officer in a gritty, realistic way that upset the prevailing view of policing as a mechanistic, black and white world of good and evil, typified by TV shows such as Dragnet and Adam-12.

No one underestimates the role Wambaugh had on policing and its perception by the public. Police officers came to understand the heroic qualities and tragic frailties of their peers and themselves. The public saw police as dedicated and brave, but imperfect human beings like themselves. Through Joseph Wambaugh’s works, policing became seen as a high-risk profession—physically and emotionally. Police Story and Hill Street Blues became the new TV paradigm of policing.

No one underestimates the role Wambaugh had on policing and its perception by the public. Police officers came to understand the heroic qualities and tragic frailties of their peers and themselves. The public saw police as dedicated and brave, but imperfect human beings like themselves. Through Joseph Wambaugh’s works, policing became seen as a high-risk profession—physically and emotionally. Police Story and Hill Street Blues became the new TV paradigm of policing.

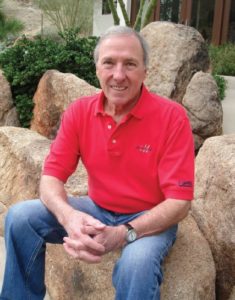

Today, Joe Wambaugh remains an astute observer of policing from the distance of his California home. He’s a husband, father and grandfather—a youthful 82 and sharp as a tack. The Quarterly had the pleasure of interviewing this most unassuming man. Here’s the conversation.

Joe, you grew up in East Pittsburgh and joined the Marine Corps at age 17. Why?

I had been living in southern California for three years before joining the USMC. I joined because after graduating from high school, I did not want to go to college, and was too young to get a decent job. Thanks to the military, I benefited from the GI bill and used it for college later on.

What inspired you to become a police officer?

I took college classes while in the military, then doubled up on classes when I left the Marine Corps at age 20, graduating with a Bachelor of Arts before my 23rd birthday. I had intended to become a teacher but saw an ad in The Los Angeles Times that the LAPD was paying $489 a month to recruits. It was very enticing, as I was bored with school and wanted some action.

At what point in your career did you decide to mix writing with policing? Did someone influence you to write?

I had majored in English and every literature major who has ever lived is a closet writer. I read John Le Carré’s spy novel, The Spy Who Came In From the Cold. For me, it was the ultimate story of police undercover work. I decided to write that novel.

I had majored in English and every literature major who has ever lived is a closet writer. I read John Le Carré’s spy novel, The Spy Who Came In From the Cold. For me, it was the ultimate story of police undercover work. I decided to write that novel.

How did you break into the publishing world?

I sent short stories to all the cheapo magazines and received rejections. I sent one story to the same magazine twice because I was convinced they had not read it the first time. It came back to me with a note: “Dear Schmuck, it’s no better this time than last time.” In desperation, I tried a literary magazine, The Atlantic Monthly. They encouraged me to try a novel. That did it; The New Centurions was the result. I could never find the “Dear Schmuck” letter to send it back to him.

Tell me about the reaction to The New Centurions.

I knew my Chief of Police would not approve of the book. I violated Departmental policy by not submitting the manuscript for editorial approval. It became the main selection of the Book of the Month Club. I received a check for $50,000 in 1970. The Chief ’s public comment was that he was glad Sergeant Wambaugh is making a lot of money because he won’t have a job much longer. The press jumped all over it. Everyone was on my side. Everyone had to see what this young cop had done. The book remained on The New York Times best seller list for 32 weeks.

You‘ve been referred to as the father of the modern police novel. Comments?

It was my intention from the beginning, to tell the story of policing from a different and more realistic perspective – the gritty, cynical, slapstick and emotional side of policing. The public was ready for truth, in place of entertaining propaganda. Jack Webb, the creator and star of Dragnet, became involved in all the kerfuffle over the release of The New Centurions. He got a man to contact me to say that Webb would read the manuscript and if it deserved to be aired, he would protect me from being fired.

My homicide partner and I drove to Sunset Boulevard in Beverly Hills and dropped off the manuscript. Well, it took a couple of weeks. I finally got a call that the manuscript was there to be picked up. We drove back in our detective car. The manuscript was in a wrapper. I said to my partner that the manuscript was heavier than when I brought it here. Every place where Webb worried about the content, he placed a paper clip – 500 in total. Every page had multiple paper clips. I kept the paperclips and never met Webb.

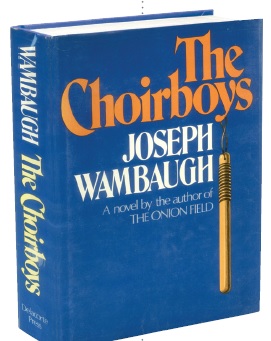

The practice of letting off steam after a shift is seen in The Choirboys. But that book also described a darker side to the police profession, in which the emotional toll can be greater than the physical danger, occasionally leading to suicide and divorce. Comments?

If I had still been in the LAPD at the time that The Choirboys was published, it would surely have gotten me fired. I have always said that the physical dangers of policing were overstated by TV shows and movies, but police officers are constantly exposed to the worst of people and ordinary people at their worst. This produces premature cynics and makes it one of the most emotionally dangerous jobs in the world.

If I had still been in the LAPD at the time that The Choirboys was published, it would surely have gotten me fired. I have always said that the physical dangers of policing were overstated by TV shows and movies, but police officers are constantly exposed to the worst of people and ordinary people at their worst. This produces premature cynics and makes it one of the most emotionally dangerous jobs in the world.

Your writing style is somewhat unconventional, described as a series of connected episodes involving colorful characters, more so than plot-driven. How did you develop this style?

The style reflects how I see life: episodic. That leads to character-driven stories, rather than plot-driven stories. I am no Agatha Christie.

What techniques did you use to document the many great stories which you fictionalized?

I took lots of secret notes as a cop and kept them in boxes and drawers in case I ever decided to try writing.

You also faced danger yourself.

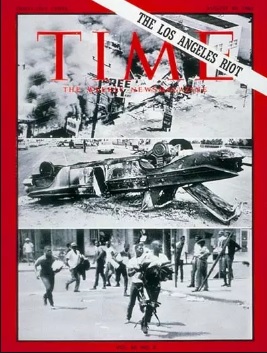

I happened to be one of a dozen besieged cops at Manchester and Vermont Streets on Friday the 13th of August 1965 when Watts erupted in rioting and all the shooting started. I don’t know if one of the hundreds of rioters fired or if it was a cop, but a couple of bodies fell. And then all hell really broke loose for three days. We were ordered to 77th Street Station earlier that afternoon from all over Los Angeles and assigned to three-man cars with cops we’d never met before. We were given a box of ammunition and a shotgun and sent to unfamiliar streets, with the intent of stopping the riots.

I happened to be one of a dozen besieged cops at Manchester and Vermont Streets on Friday the 13th of August 1965 when Watts erupted in rioting and all the shooting started. I don’t know if one of the hundreds of rioters fired or if it was a cop, but a couple of bodies fell. And then all hell really broke loose for three days. We were ordered to 77th Street Station earlier that afternoon from all over Los Angeles and assigned to three-man cars with cops we’d never met before. We were given a box of ammunition and a shotgun and sent to unfamiliar streets, with the intent of stopping the riots.

It was not police work, but a crazy kind of urban combat in a state of anarchy. We mainly tried to protect each other while mobs looted. The windows were smashed from our car within minutes, and at some point, one of the cops I was teamed with fired a shotgun blast in the general direction of a muzzle flash and managed to hit a looter in the ankle with one pellet of double- aught buckshot. Taking that looter for medical treatment and then to jail got us off the street for nearly two hours and was a welcome relief, ut then it was back out to hell. Anyway, that wasn’t really police work.

Joe, tell me then about a police incident that had a lasting impact on you.

I was a patrol officer in south central L.A. We had a lot of shootings and action. I was training rookie named Fred Early. He was only out of the Academy for matter of weeks. We got a call of shots fired at a pool hall and arrived just ahead of another black and white. A guy stepped out of the pool hall with a shotgun. Pellets whiz past us and he heads back inside.

I didn’t pay attention to Fred Early. Everyone was yelling, and the radio was blaring. It turns out that Fred had run around the building and covered the back door. He was assertive and smart. The robber runs out the back door holding the shotgun at port arms. Fred fired one round. I arrived to find the suspect on his back with a grimace on his face and a hole between his eyes.

I didn’t pay attention to Fred Early. Everyone was yelling, and the radio was blaring. It turns out that Fred had run around the building and covered the back door. He was assertive and smart. The robber runs out the back door holding the shotgun at port arms. Fred fired one round. I arrived to find the suspect on his back with a grimace on his face and a hole between his eyes.

That, however, wasn’t the end of the story. Five years later, Fred Early was on his way home from work. Something happened. He reported a burglar breaking into a commercial business. He tried to arrest the suspect. A fight ensued, he was repeatedly beaten and kicked in the head by his assailant and shot in the leg with his own gun. The guy got away. Fred eventually died during one of his surgeries, having suffered irreversible brain damage.

You’re a New York Times bestselling author and the winner of many awards, including Grand Master of the Mystery Writers of America. Did you anticipate your novels’ impact and it would become next to impossible for you to resume work as a homicide detective?

Nobody could have anticipated the instant success. I simply wanted to publish something. I never dreamed that I would be unable to complete my 20 years with the LAPD and get my pension, the security blanket all cops want. Many times, I regretted my success. Fourteen years was seventy per cent of what I agreed to serve. I thought about it a thousand times. I would love to just have completed it. Also, in those years, I was used to packing a gun and no longer had a right to carry a gun.

Do you have a favorite character in your novels?

I don’t really have a favorite character, but nonfiction books are like my step-children, novels are like my biological children.

Is Joe Wambaugh in the novels himself?

Pieces of me are probably in some of the fictional characters.

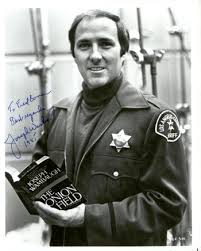

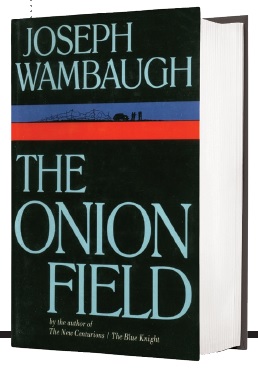

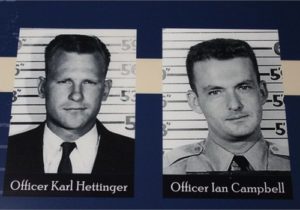

At some point, you decided to write non-fiction, beginning with The Onion Field, which was a huge hit. Why did you expand from the fiction genre?

I knew there was a great true story that had to be told, not so much about the murdered officer, Ian Campbell, but about the survivor, Karl Hettinger. I was working Wilshire Vice the night that Campbell and Hettinger were kidnapped in Hollywood Division, the next division north of us. Everyone was looking for them. I stayed close to the case. When I heard what happened to Hettinger within the Department, I knew it was wrong and that he would pay a terrible price. He surely did.

I knew there was a great true story that had to be told, not so much about the murdered officer, Ian Campbell, but about the survivor, Karl Hettinger. I was working Wilshire Vice the night that Campbell and Hettinger were kidnapped in Hollywood Division, the next division north of us. Everyone was looking for them. I stayed close to the case. When I heard what happened to Hettinger within the Department, I knew it was wrong and that he would pay a terrible price. He surely did.

Your books spawned TV shows and movies and turned the existing genre of television shows, such as Dragnet and Adam-12, on their head, helping spawn a new paradigm, typified by Police Story and Hill Street Blues. Thoughts?

I’ll give you an example. I worked on Police Story which aired on NBC television. After some rookies have a year or so under their belt, their badge starts to feel heavy and they begin to swagger a bit. We created an episode about what we, at LAPD called the John Wayne Syndrome. For some reason, the producer submitted the script to John Wayne Productions. Their response— “absolutely not.”

The production company got cold feet and changed the term to the Wyatt Earp Syndrome. The badge heavy cop loses everything, including his wife. At the end of the episode he is seen sitting on the bed of his empty apartment. The tough guy suddenly breaks down weeping and the show ends with the sound of a radio call playing over his sobs.

Using a radio call has become a part of line of duty police funerals, where the fallen officer is called on the police radio and fails to respond. Did this tradition begin with your writing?

Not to my knowledge. However, not being too vain, the tradition of playing bagpipes at police funerals started after The Onion Field was published. The book introduced it by recounting Officer Ian Campbell’s funeral. His grandparents on both sides were from Scotland and Ian loved everything Scottish. There is a photo of him playing the bagpipes. They were played at his funeral, and this was repeated in the movie. It was heartbreaking.

Not to my knowledge. However, not being too vain, the tradition of playing bagpipes at police funerals started after The Onion Field was published. The book introduced it by recounting Officer Ian Campbell’s funeral. His grandparents on both sides were from Scotland and Ian loved everything Scottish. There is a photo of him playing the bagpipes. They were played at his funeral, and this was repeated in the movie. It was heartbreaking.

Another non-fiction book, The Blooding, tells the story of the first successful use of DNA profiling, which occurred in England. How did you learn of this case and did you anticipate the huge impact that DNA would have on policing?

I read about the case and knew at once, if it could be true, that this would be the biggest event in crime detection since inked fingerprinting.

One of your most entertaining books must be The Black Marble, a story about dog shows and crime. But there appears to be a deeper meaning in this and other books, which appear to use satire to pan the excesses of modern American society.

That is probably true. As with most of my work, all the comedy is tempered by some intense and painful scenes involving PTSD in police work. I really liked the movie of Black Marble, but the mix of funny and harrowing stories, including the torture and death of a child and a cop going crazy, confused some viewers who either loved or hated it. Harry Dean Stanton was a great comedic villain in the movie.

That is probably true. As with most of my work, all the comedy is tempered by some intense and painful scenes involving PTSD in police work. I really liked the movie of Black Marble, but the mix of funny and harrowing stories, including the torture and death of a child and a cop going crazy, confused some viewers who either loved or hated it. Harry Dean Stanton was a great comedic villain in the movie.

Do you have a sense of the impact that your books had outside the United States?

My books are fading into distant memory. I’m not sure that there is a large society of avid book readers left, anywhere in the world. At the time, however, I met cops in Europe, Australia and New Zealand during book tours. I did become aware of their impact. It was very flattering.

Have you visited Canada and met Canadian police officers?

I did the book tour to large cities and met a few Canadian coppers. I also spent a month in Toronto prepping Echoes in the Darkness, a TV mini-series, where we made Toronto look like Philadelphia. We brought in palm trees and placed them on the shore of Lake Ontario, turning it into Miami! One day in April it was so hot that we were in t-shirts. The next morning, the snow was six inches deep! While in Toronto, we had to fly to New York to interview actors, but everyone had the same feeling—New York was foreign to us, Toronto was like home. Such a great city. I thought about it the other day when I read about a terrible shooting in Greektown. I used to go there all the time for dinner.

Would you recommend a policing career to young people today?

All my life I’ve seen it getting worse and worse. The police can do no right. They are criticized more and more. Criticism starts before the facts come out.

All my life I’ve seen it getting worse and worse. The police can do no right. They are criticized more and more. Criticism starts before the facts come out.

One important point in terms of police shootings. The critics are endless. So called bad or shaky shootings arise from fear not anger. Fear is the motivator in the case of bad shootings. Shootings arising from police rage are uncommon. This is a fundamental thing that has to be understood. I would not recommend policing as a career today.

How does Joe Wambaugh spend his time today?

Dee and I married when I was an 18-year-old Marine and we have two children and two grandchildren. I hate the idea of retirement. The worst part of old age is the loss of creative energy and being unable to write more books. Three of my four grandparents were Irish immigrants – the fourth being a German-American originally named Wambach – so mostly Irish DNA means that I tend to see the world and my life through a glass darkly. On the other hand, it is probably my Irish DNA that made me a writer in the first place. So, what do I have to bitch about? Semper cop!