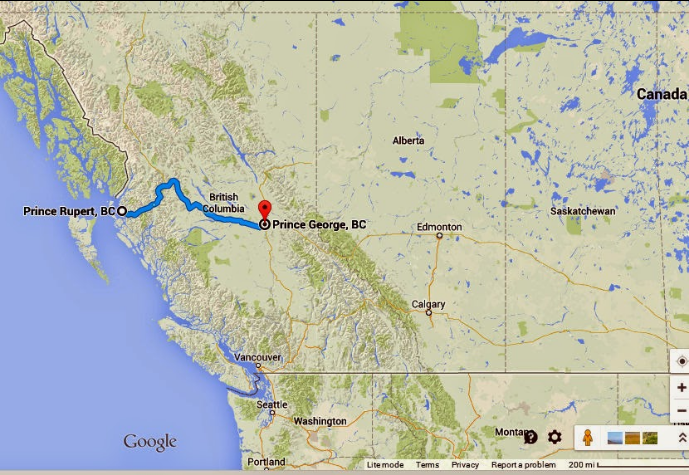

There’s a lonely road stretch in remote northwestern British Columbia, Canada having a huge number of unsolved missing and murdered women cases. It spans 450 miles between the small cities of Prince George in the province’s interior and Prince Rupert on the Pacific coast. Over the past 40 years, more than 40 women mysteriously disappeared or died from foul play in that area. Most of their circumstances remain unknown. The road’s geographically known as #16 or the Yellowhead Route but—for good reason—locals call it the Highway of Tears.

There’s a lonely road stretch in remote northwestern British Columbia, Canada having a huge number of unsolved missing and murdered women cases. It spans 450 miles between the small cities of Prince George in the province’s interior and Prince Rupert on the Pacific coast. Over the past 40 years, more than 40 women mysteriously disappeared or died from foul play in that area. Most of their circumstances remain unknown. The road’s geographically known as #16 or the Yellowhead Route but—for good reason—locals call it the Highway of Tears.

The Highway of Tears murders and the women’s suspicious disappearances began in 1969. They continue today with the last case of modus operandi (MO) similarities happening in December 2018. Although police officially remain cautious about confirming links, many in-the-know suspect there may be many more crimes with victims fitting the mold.

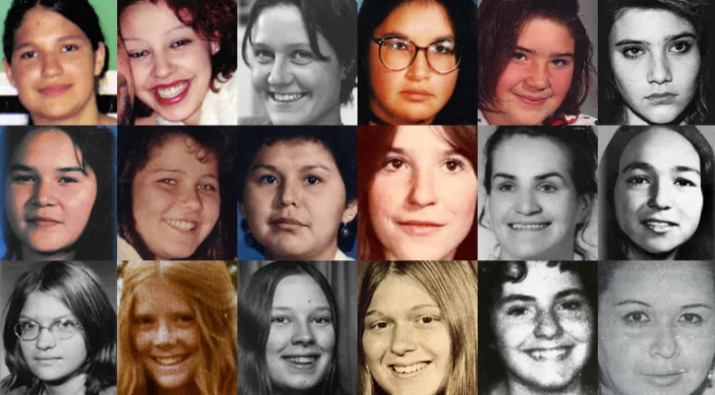

In 2005, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) formed a task force called E-Pana to look at the area’s unsolved missing and murdered women cases. The RCMP is Canada’s federal force having jurisdiction across the nation and in the region. The task force initially identified 18 cases but soon expanded their investigation to include similar files eastward along Route 16 to Hinton, Alberta as well as south along Highway 97 to Kamloops, BC and along Highway 5 from Merritt to Clearwater.

In 2005, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) formed a task force called E-Pana to look at the area’s unsolved missing and murdered women cases. The RCMP is Canada’s federal force having jurisdiction across the nation and in the region. The task force initially identified 18 cases but soon expanded their investigation to include similar files eastward along Route 16 to Hinton, Alberta as well as south along Highway 97 to Kamloops, BC and along Highway 5 from Merritt to Clearwater.

Two significant independent government inquiries or investigations into the Highway of Tears and related matters also happened. One was a British Columbia Provincial Symposium held in 2006. The other—a recent, national commission called the Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women Inquiry. It’s called that because many victims were of indigenous or First Nations ethnicity.

Despite the massive police and public effort, no one’s been caught for most of the crimes. As well, many of the victim’s bodies remain hidden and undiscovered. That leaves people wondering if there’s a serial killer loose on the Highway of Tears.

The Highway of Tears Victims

Without exception, every victim in the Highway of Tears (HOT) sphere is female. That includes confirmed murders as well as unsolved disappearances. Another harsh fact is many victims originated from aboriginal or First Nations backgrounds. It’s a reality that can’t be overlooked.

Project E-Pana (named so after the Inuit spirit that guides souls to the afterlife) used four criteria to qualify a murder or suspicious disappearance as a Highway of Tears or HOT case. These parameters were sound and valid, as many homicide and missing persons cases in the north have other circumstances that don’t suggest a commonality the HOT files have. Out of great precaution, HOT investigators are very careful about using the “SK-word”—Serial Killer. To be on the HOT list, the E-Pana victim profiles are:

- Female

- High-risk lifestyle

- Known to hitchhike

- Found or last seen near Highways 16, 97 & 5

Females who hitchhike and practice a high-risk lifestyle around this remote road network are easy prey. Many come from physical, sexual and substance abusive backgrounds. Many are sex workers and drug users as well as having alcoholic tendencies and serious mental/emotional disorders. And, many women victims are from indigenous communities with a host of social problems.

Police investigators feel most, if not all, Highway of Tears cases are stranger-to-stranger relationships. Police don’t like the serial killer term because of public ramifications, but it’s a classic serial killer pattern to pick up strangers and have their way. Most lone-operating killers leave little evidence behind at their crime scenes, take little with them, make sure there are no independent witnesses and they rarely confess. That combination makes these predators so hard to catch.

First Nations women are particularly vulnerable. Along the main Highway of Tears stretch from Prince Rupert to Prince George there are 23 different indigenous communities or reserves. Most of these little places have few facilities like medical services, educational outlets and recreational opportunities. As well, poverty is a gigantic problem in Canada’s First Peoples settlements. They simply can’t afford private transportation.

First Nations women are particularly vulnerable. Along the main Highway of Tears stretch from Prince Rupert to Prince George there are 23 different indigenous communities or reserves. Most of these little places have few facilities like medical services, educational outlets and recreational opportunities. As well, poverty is a gigantic problem in Canada’s First Peoples settlements. They simply can’t afford private transportation.

Combined with personal issues and the need to be mobile, many at-risk women are alone on side of the road with their thumb out. They’re perfect opportunities for men with deviant desire. Here is a list of who fell victim in the deadly web called the Highway of Tears and throughout the entire region.

- Gloria Moody — 27, Murdered near Williams Lake, October 1969

- Micheline Pare — 18, Murdered near Hudson’s Hope, July 1970

- Helen Claire Frost — 15, Missing from Prince George, October 1970

- Jean Virginia Sampare — 18, Missing from Hazelton, October 1971

- Gayle Weys — 19, Murdered near Clearwater, October 1973

- Pamela Darlington — 19, Murdered at Kamloops, November 1973

- Coleen MacMillan — 16, Murdered near Lac La Hache, August 1974

- Monica Ignas — 15, Murdered near Terrace, December 1974

- Mary Jane Hill — 31, Murdered at Prince Rupert, March 1978

- Monica Jack — 12, Murdered near Merritt, May 1978

- Maureen Mosie — 33, Murdered near Salmon Arm, May 1981

- Jean May Kovacs — 36, Murdered at Prince George, October 1981

- Roswitha Fuchsbichler — 13, Murdered at Prince George, November 1981

- Nina Marie Joseph — 15, Murdered at Prince George, August 1982

- Shelley-Anne Bascu — 16, Missing from Hinton, May 1983

- Alberta Gail Williams — 24, Murdered near Prince Rupert, August 1989

- Cecilia Anne Nikal — 15, Missing from Smithers, October 1989

- Delphine Anne Nikal — 15, Missing from Smithers, June 1990

- Theresa Umphrey — 38, Murdered near Prince George, February 1993

- Marnie Blanchard — 18, Murdered near Prince George, March 1993

- Ramona Lisa Wilson — 16, Murdered near Smithers, June 1994

- Roxanne Thiara — 15, Murdered near Burns Lake, November 1994

- Alishia Leah Germaine — 15, Murdered at Prince George, November 1994

- Lana Derrick — 19, Missing from Terrace, October 1995

- Deena Braem — 16, Murdered near Quesnel, September 1999

- Monica McKay — 18, Murdered at Prince Rupert, December 1999

- Nicole Hoar — 24, Missing from Prince George, June 2002

- Mary Madeline George — 25, Missing from Prince George, July 2005

- Tamara Lynn Chipman — 22, Missing from Prince Rupert, September 2005

- Aielah Saric Auger — 14, Murdered at Prince George, February 2006

- Beverly Warbick — 20, Missing from Prince George, June 2007

- Bonnie Marie Joseph — 32, Missing from Vanderhoof, September 2007

- Jill Stacey Stuchenko — 35, Murdered near Prince George, October 2009

- Emmalee Rose McLean — 16, Murdered at Prince Rupert, April 2010

- Natasha Lynn Montgomery — 23, Murdered at Prince George, August 2010

- Cynthia Frances Maas— 35, Murdered near Prince George, September 2010

- Loren Dawn Leslie — 15, Murdered near Prince George, November 2010

- Madison “Maddy” Scott — 20, Missing near Vanderhoof, May 2011

- Immaculate “Mackie” Basil — 26, Missing near Fort St. James, June 2013

- Anita Florence Thorne — 49, Missing from Prince George, November 2014

- Roberta Marie Sims — 55, Missing from Prince George, May 2017

- Frances Brown — 53, Missing near Smithers, October 2017

- Chantelle Catherine Simpson — 34, Suspicious Death at Terrace, July 2018

- Jessica Patrick — 18, Murdered near Smithers, September 2018

- Cynthia Martin — 50, Missing near Hazelton, December 2018

The Case for a Highway of Tears Serial Killer

These 40+ known cases all have a similarity beyond the E-Pana parameters. That’s the peculiar pattern of how they met their fate. Investigators assume most victims did not know their assailant and unsuspectingly fell into a fatal trap. And that trap may have been set by a serial offender.

Before assuming that one or more serial killers have been on the loose in the E-Pana project and the entire cases associated to the general Highway of Tears area, it’s necessary to define what a serial killer is. According to the United States Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), a serial killer is an offender who commits “a series of two or more murders, committed as separate events, usually, but not always, by one offender acting alone.” Serial murder is defined as “the unlawful killing of two or more victims by the same offender(s), in separate events.”

Before assuming that one or more serial killers have been on the loose in the E-Pana project and the entire cases associated to the general Highway of Tears area, it’s necessary to define what a serial killer is. According to the United States Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), a serial killer is an offender who commits “a series of two or more murders, committed as separate events, usually, but not always, by one offender acting alone.” Serial murder is defined as “the unlawful killing of two or more victims by the same offender(s), in separate events.”

This is a fairly tight description for a multiple killer. It fits someone on a path or destiny rather than a mass-murderer who goes on one rampage and causes numerous deaths. Most people associate serial killers with notorious Americans like Ted Bundy, Gary Ridgway or Albert DeSalvo. They were particularly nasty people. But, British Columbia had its share of these vicious villains. Noteworthy BC serial killers were Clifford Olson who killed 10 or more children and Robert “Willie” Pickton who did-in 49 women and fed them to his pigs.

Most serial killers operate alone and have a distinctive pattern or modus operandi. Experienced police investigators know to look for crime patterns and identify similarities. One of the main indicators is victim profiling. In almost all of the cases brought under the Highway of Tears investigation umbrella, the victim’s background and vulnerability stand out. Other indicators are the time frame and location.

In missing persons cases, investigators naturally start with where and when the victim was last seen. They also look for abandoned items such as a vehicle, their purse and contents or their phone. Where bodies are found, investigators look for the mechanism or means of death. Most of the Highway of Tears and related victims were strangled—the exact strangulation method being held back as it’s known only to the police and the perpetrator.

In missing persons cases, investigators naturally start with where and when the victim was last seen. They also look for abandoned items such as a vehicle, their purse and contents or their phone. Where bodies are found, investigators look for the mechanism or means of death. Most of the Highway of Tears and related victims were strangled—the exact strangulation method being held back as it’s known only to the police and the perpetrator.

In the Highway of Tears periphery—and it is a periphery because what started as an investigation along the Prince George to Prince Rupert road quickly branched off to a much bigger area where a mobile serial killer could have easily traveled within a day. What’s really notable in this overall murder and missing persons combined investigation are the time periods. There are nine distinct activity calendar groups:

- 1969-1974

- 1978

- 1981-1983

- 1989-1990

- 1993-1995

- 1999-2002

- 2005-2007

- 2009-2014

- 2017-2018

This date grouping shows a burst of start-stop, start-stop and start-stop. There could be many reasons for this such as the perpetrator being repeatedly incarcerated, moving out of the geographical area or, in the case of Gary Ridgway—the Green River Killer from Seattle—he nearly got caught and thought he’d give it a rest for a while. But, it seems more likely there are multiple offenders in the overall Highway of Tears file. In fact, police have already caught, convicted or identified five different HOT-profile men.

The Police Catch or Identify Serial Killers in the Highway of Tears Investigation

To be fair, not all the murdered or missing women in the previous list are true Highway of Tears victims from BC Highways 16, 97 & 5. As the investigation grew, it expanded to include a wide net of confirmed or suspected murders across the mid-section of semi-rural British Columbia. That was a natural progression. It’s a logical and competent way of investigating a broad range of offense dates and locations.

Long before the E-Pana probe in 2005, which started as a look at the cases on Highway 16 between Prince George and Prince Rupert, the RCMP knew there was a pattern emerging. In 1981, they held a multi-jurisdictional meeting called The Highway Murders Conference to look at commonalities of historic unsolved murders and missing persons cases. Over 40 detectives from across BC and Alberta met in Kamloops and presented their case facts. This was the original start to a massive investigation that’s still highly-active today.

Long before the E-Pana probe in 2005, which started as a look at the cases on Highway 16 between Prince George and Prince Rupert, the RCMP knew there was a pattern emerging. In 1981, they held a multi-jurisdictional meeting called The Highway Murders Conference to look at commonalities of historic unsolved murders and missing persons cases. Over 40 detectives from across BC and Alberta met in Kamloops and presented their case facts. This was the original start to a massive investigation that’s still highly-active today.

In the years following the Highway Murder Conference, the RCMP and other law enforcement agencies solved some of the “HOT” killings and disappearances. They were able to profile offenders under the FBI’s serial killer definition. Here are the five serial killers known to have committed murders on the overall HOT list.

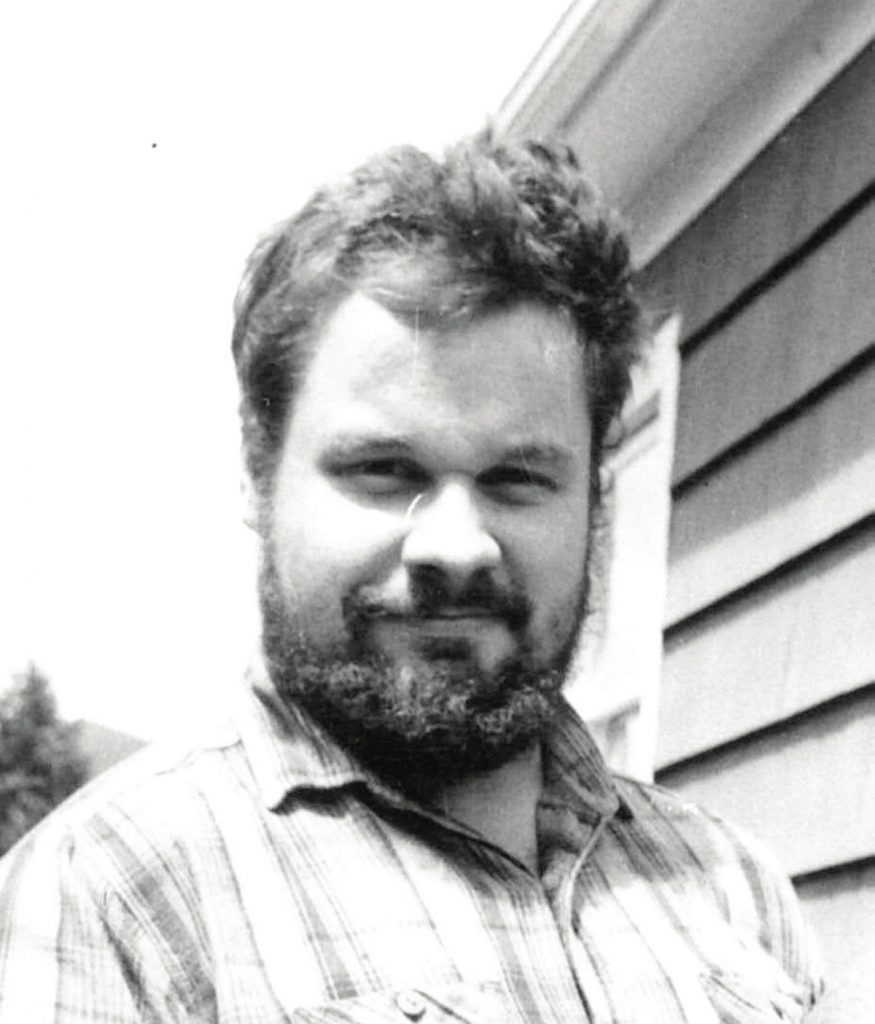

1. Cody Alan Legebokoff — He was convicted of the 2009/2010 Jill Stuchenko, Natasha Montgomery, Loren Leslie and Cynthia Maas murders near Prince George. Legebokoff is serving life in prison.

2. Brian Peter Arp — He was convicted of the 1989 near-Prince George murders of Theresa Umphrey and Marnie Blanchard. Arp is also serving a life sentence.

3. Edward Dennis Issac — He was convicted of the 1981/1892 murders of Nina Joseph, Jean Kovacs and Roswitha Fuchsbichler in Prince George. Issac is still serving out his life sentence

4, Gary Wayne Hanlin — He was convicted of the 1978 Monica Jack murder at Merritt and faces new charges for killing another pre-teen girl. Hanlin got a life sentence, as well.

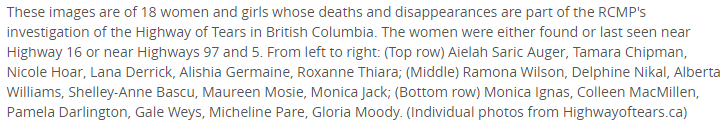

5. Bobby Jack Fowler — This known serial killer died in an Oregon prison in 1986. Post-death DNA analysis linked Fowler to causing the 1973/1974 Kamloops area murders of Coleen McMillan, Gail Weys and Pamela Darlington. Given the time frame pattern and location, Fowler may also have killed Monica Ignas in Terrace.

The Highway of Tears Public Investigations and Inquiries

Over the years, the mass of unsolved murders and missing women’s cases have been front and center in British Columbia and Canadian spectrums. Local, national and international interest spread, and took on a scope much larger than the cases committed along the original roadway called the Highway of Tears. Hundreds of thousands of hours and millions of dollar have been exhausted trying to rectify what went wrong and how future tragedies could be prevented.

In 2006, the British Columbia probe called the Highway of Tears Symposium released a report with an objective look at the entire factors causing victim vulnerability. They made rational and constructive recommendations that, if correctly implemented, could drastically reduce the potential for other women to end up on the HOT list. The symposium divided their solution into these four categories:

- Victim Prevention

- Emergency Planning and Team Readiness

- Victim Family Counselling and Support

- Community Development and Support

The Highway of Tears Symposium offered 33 separate recommendations on how to reduce victim risk and how to organize a holistic crime prevention program throughout the at-risk region. Most of the recommendations were solid, common-sense steps that could be practically implemented. One of the primary actions was to increase public transit along Highway 16 so the women wouldn’t need to hitchhike.

The Highway of Tears Symposium offered 33 separate recommendations on how to reduce victim risk and how to organize a holistic crime prevention program throughout the at-risk region. Most of the recommendations were solid, common-sense steps that could be practically implemented. One of the primary actions was to increase public transit along Highway 16 so the women wouldn’t need to hitchhike.

Other smart points in the action plan were making the police and public officials more responsible for spotting women placing themselves at risk and intervening on the side of the road. The report recommended a network of safe houses and a community watch program be integrated across the area. Many more recommendations addressed education and economic support for vulnerable women.

It’s been 13 years since the Highway of Tears Symposium did its necessary and valuable work. Sadly, very few of their well-thought-out suggestions ever materialized. An example is that it took 11 years before a simple and reliably-scheduled public transit bus service hit the Yellowhead Highway. Some of the risk prevention literature has been well written and promoted, though.

The Canadian Federal Government’s cross-country consortium called the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls (IMMIWG) took public problem probing to a whole new level. What started as a Highway of Tears inquiry expanding the plight of First Nations women turned into a f-fest where three of the leading commissioners quit in frustration and disgust. It seemed everyone with a grievance to grind and an agenda to advance hijacked the focus and spun it around. By the time the $53.8 million off-track inquisition ended, the indigenous women core concern expanded to include every fringe interest lumped into a category called 2SLGBTQQIA. That’s an acronym for 2 Spirit, Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer, Questioning, Intersex and Asexual.

On June 4, 2019, the Canadian Prime Minister championed the IMMIWG report release with this quote, “Earlier this morning, the national inquiry formally presented their report, in which they found that the tragic violence that Indigenous women and girls have experienced amounts to genocide”. The Prime Minister’s critics were quick to point out the United Nations definition of genocide:

“Any of the following acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group, as such: killing members of the group; causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group; deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life, calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part; imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group; [and] forcibly transferring children of the group to another group.”

What started as a well-intentioned review of what happened to cause the Highway of Tears-related murders and suspicious disappearances totally missed the mark in the Canadian Federal Government’s sights. While the HOT Symposium operated with honorable intentions, the IMMIWG was a farce. It contributed little, if nothing, to the cause and likely did more harm than good. The IMMIWG failed to make positive recommendations for future harm prevention and investigation improvements. Ultimately, the IMMIWG blamed colonialism for oppressive behavior on margins of society. It seems the IMMIWG forgot many of the Highway of Tears victims were white heterosexual women born and raised in mainstream Canada.

Is a Serial Killer Loose on the Highway of Tears?

The answer is yes and no. There isn’t , and never has been, one lone serial killer continually at work on the Highway of Tears or in the surrounding geographical area. The right answer is there are many serial killers out there who’ve traveled those remote highways for years. Without a doubt, at least five separate serial killers contributed to some of the forty-year carnage. It’s highly-likely a large number of the yet-unsolved cases are the work of still-to-be-caught perpetrators. And, it’s also highly-likely some murders and abductions are one-offs.

Will all the Highway of Tears related murders eventually be solved? It’s highly-unlikely that’ll happen given the time gone by and the limited evidence available. However, there’s good reason to be optimistic some old and cold cases will be cleared. Back in the 70s, no one saw how powerful forensic DNA typing would be. We’re only now starting to tap the new familial database mines. Back in the 70s, no one saw how effective the Mister Big undercover sting would work on serial killers. And, back in the 70s, information sharing was nothing like what’s happening today.

Will all the Highway of Tears related murders eventually be solved? It’s highly-unlikely that’ll happen given the time gone by and the limited evidence available. However, there’s good reason to be optimistic some old and cold cases will be cleared. Back in the 70s, no one saw how powerful forensic DNA typing would be. We’re only now starting to tap the new familial database mines. Back in the 70s, no one saw how effective the Mister Big undercover sting would work on serial killers. And, back in the 70s, information sharing was nothing like what’s happening today.

So, no one knows what’s to come. Thanks to high-tech science combining with cool cop creative minds, we’re in for an interesting crime-solving drive down the Highway of Tears.