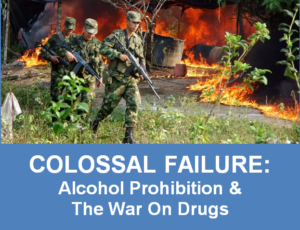

“Insanity is doing the same thing over and over and expecting different results,” said Albert Einstein. Such can apply to two enormous social experiments costing trillions in U.S. dollars and countless American lives. Alcohol prohibition in the 1920s and the 50-year losing streak against “drugs”—the new Public Enemy Number One—flat-out never worked. Is it finally time to admit colossal failure, give up, and legalize all intoxicating substances?

“Insanity is doing the same thing over and over and expecting different results,” said Albert Einstein. Such can apply to two enormous social experiments costing trillions in U.S. dollars and countless American lives. Alcohol prohibition in the 1920s and the 50-year losing streak against “drugs”—the new Public Enemy Number One—flat-out never worked. Is it finally time to admit colossal failure, give up, and legalize all intoxicating substances?

I ask this question seriously. I’m one of the few people my age who’s never done “drugs”, not so much as a puff off a joint. However, I’ve downed enough booze to drown a humpback. And as I look back at 65 years of life, I’d be a hypocrite to sit here with my glass of Pinot Gris or Cab Sav and call down a pot smoker.

What got me going on legalizing drugs is a new writing/content-creating project I’m into. City Of Danger is my netstream-style series and I’m in deep research mode. The series core—it’s theme, you could call it—is “the more things change, the more they stay the same”. It’s a juxtaposition between the Roaring Twenties when Prohibition was in full swing and the Fizzling 2020s when society has succumbed to crime and corruption. Watch for the pilot episode in late fall/early winter.

The City Of Danger series is a social comment. It features two 1920s-era private detectives transposed in time to help a modern city in crisis dispense street justice and restore social order. And isn’t that exactly what alcohol prohibition and the war on drugs was supposed to do?

Before we come to my personal opinion and conclusion about legalizing all intoxicating substances, let’s look back on how Prohibition and the War On Drugs came to be and why they colossally failed.

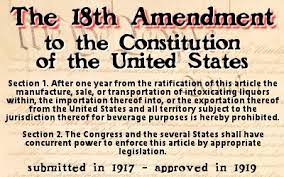

The Eighteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution

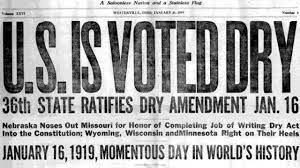

“The Eighteenth Amendment (Amendment XVIII) of the United States Constitution established the prohibition of alcohol in the United States. The amendment was proposed by Congress on December 18, 1917, and was ratified by the requisite number of states on January 16, 1919. The Eighteenth Amendment was repealed by the Twenty-first Amendment on December 5, 1933. It is the only amendment to be repealed.

The Eighteenth Amendment was the product of decades of efforts by the temperance movement, which held that a ban on the sale of alcohol would ameliorate poverty and other societal issues. The Eighteenth Amendment declared the production, transport, and sale of intoxicating liquors illegal, though it did not outlaw the actual consumption of alcohol. Shortly after the amendment was ratified, Congress passed the Volstead Act to provide for the federal enforcement of Prohibition. The Volstead Act declared that liquor, wine, and beer all qualified as intoxicating liquors and were therefore prohibited. Under the terms of the Eighteenth Amendment, Prohibition began on January 17, 1920, one year after the amendment was ratified.

Although the Eighteenth Amendment led to a minor decline in alcohol consumption in the United States, nationwide enforcement of Prohibition proved difficult, particularly in cities. Rum-running (bootlegging) and speakeasies (booze cans) became popular in many areas. Public sentiment began to turn against Prohibition during the 1920s, and 1932 Democratic presidential nominee Franklin D. Roosevelt called for its repeal. The Twenty-first Amendment finally did repeal the Eighteenth in 1933, making the Eighteenth Amendment the only one so far to be repealed in its entirety.” ~Wikipedia Quote

Although the Eighteenth Amendment led to a minor decline in alcohol consumption in the United States, nationwide enforcement of Prohibition proved difficult, particularly in cities. Rum-running (bootlegging) and speakeasies (booze cans) became popular in many areas. Public sentiment began to turn against Prohibition during the 1920s, and 1932 Democratic presidential nominee Franklin D. Roosevelt called for its repeal. The Twenty-first Amendment finally did repeal the Eighteenth in 1933, making the Eighteenth Amendment the only one so far to be repealed in its entirety.” ~Wikipedia Quote

The Eighteenth Amendment wording is:

Section 1. After one year from the ratification of this article the manufacture, sale, or transportation of intoxicating liquors within, the importation thereof into, or the exportation thereof from the United States and all the territory subject to the jurisdiction thereof for beverage purposes is hereby prohibited.

Section 2. The Congress and the several States shall have concurrent power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.

Section 3. This article shall be inoperative unless it shall have been ratified as an amendment to the Constitution by the legislatures of the several States, as provided in the Constitution, within seven years from the date of the submission hereof to the States by the Congress.

Prohibition of alcohol didn’t happen overnight in America. The temperance movement had been building for several hundred years and was a strong social divide across gender, race, ethnic origin, religion, and class status; ie wealth and power. The social division before 1920 when Prohibition was enacted and enforced was severe. In one camp were the “drys” who opposed all alcohol forms. In the other were the “wets” who saw nothing wrong with drinking’s status quo.

Prohibition of alcohol didn’t happen overnight in America. The temperance movement had been building for several hundred years and was a strong social divide across gender, race, ethnic origin, religion, and class status; ie wealth and power. The social division before 1920 when Prohibition was enacted and enforced was severe. In one camp were the “drys” who opposed all alcohol forms. In the other were the “wets” who saw nothing wrong with drinking’s status quo.

Then there were the moderates who believed in alcohol tolerance with strings attached to safely regulate the booze business. A 1784 treatise titled The Inquiry into the Effects of Ardent Spirits Upon the Human Body and Mind argued in favor of limited medicinal alcohol use and controlling excess by educating society on the dangers of overindulgence. The report labeled drunkenness as a disease to be controlled and treated, not an offense to be prohibited and punished.

Those views changed over the century and a half while the temperance movement gained traction. Middle-class women earned enormous clout as moral authorities in the household. Most believed alcohol was a threat to the home and, in many cases, they were right.

A conflict of values between rural Protestant America and the liberal urbanites emerged and this turned political. Votes being votes, the temperance and prohibitive forces seized on the sentiment of the day, and the Eighteenth Amendment became law.

Despite the Volstead Act authorizing federal, state, and local authorities, there was little law enforcement will to stop the manufacture, sale, or transportation of intoxicating liquors within, the importation thereof into, or the exportation thereof from the United States. With government out of the picture, or at best, sitting on the sidelines, civilian forces took control of the alcoholic beverage industry and profited—profiting enormously is an understatement.

Prohibition caused the mobster/gangster culture complete with turf wars and assassinations by Tommygun. Gangsters thrived while they were alive and the public starved from the loss of legitimate employment in the liquor business and the drop in tax revenues. Cities like Chicago and New York partied with thousands of illegal speakeasies which the local police turned a blind eye to, and the feds—the revenuers—had horribly inadequate resources to do anything but chase hillbilly moonshiners and bust the odd still.

Then came Black Friday and the start of the Great Depression which bled into the Dirty Thirties. Crime had won and the temperates lost. Public opinion turned and shaped new prohibition policies which basically said, “We’ve lost the black market battle. The intoxicant war can’t be won. It’s time to make alcohol legal again.” The move towards repealing the Eighteenth Amendment took hold.

— — —

When Prohibition was introduced, I hoped that it would be widely supported by public opinion and the day would soon come when the evil effects of alcohol would be recognized. I have slowly and reluctantly come to believe that this has not been the result. Instead, drinking has generally increased; the speakeasy has replaced the saloon; a vast army of lawbreakers has appeared; many of our best citizens have openly ignored Prohibition; respect for the law has been greatly lessened, and crime has increased to a level never seen before. ~John D. Rockefeller in open 1932 letter to the New York Times

— — —

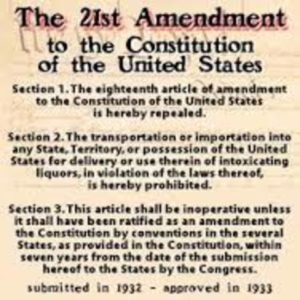

The Twenty-First Amendment of the United States Constitution

“The Twenty-first Amendment (Amendment XXI) to the United States Constitution repealed the Eighteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, which had mandated nationwide prohibition on alcohol. The Twenty-first Amendment was proposed by the 72nd Congress on February 20, 1933, and was ratified by the requisite number of states on December 5, 1933. It is unique among the 27 amendments of the U.S. Constitution for being the only one to repeal a prior amendment, as well as being the only amendment to have been ratified by state ratifying conventions.

The Eighteenth Amendment was ratified on January 16, 1919, the result of years of advocacy by the temperance movement. The subsequent passage of the Volstead Act established federal enforcement of the nationwide prohibition on alcohol. As many Americans continued to drink despite the amendment, Prohibition gave rise to a profitable black market for alcohol, fueling the rise of organized crime. Throughout the 1920s, Americans increasingly came to see Prohibition as unenforceable, and a movement to repeal the Eighteenth Amendment grew until the Twenty-first Amendment was ratified in 1933.

The Eighteenth Amendment was ratified on January 16, 1919, the result of years of advocacy by the temperance movement. The subsequent passage of the Volstead Act established federal enforcement of the nationwide prohibition on alcohol. As many Americans continued to drink despite the amendment, Prohibition gave rise to a profitable black market for alcohol, fueling the rise of organized crime. Throughout the 1920s, Americans increasingly came to see Prohibition as unenforceable, and a movement to repeal the Eighteenth Amendment grew until the Twenty-first Amendment was ratified in 1933.

Section 1 of the Twenty-first Amendment expressly repeals the Eighteenth Amendment. Section 2 bans the importation of alcohol into states and territories that have laws prohibiting the importation or consumption of alcohol. Several states continued to be “dry states” in the years after the repeal of the Eighteenth Amendment, but in 1966 the last dry state (Mississippi) legalized the consumption of alcohol. Nonetheless, several states continue to closely regulate the distribution of alcohol. Many states delegate their power to ban the importation of alcohol to counties and municipalities, and there are numerous dry communities throughout the United States. Section 2 has occasionally arisen as an issue in Supreme Court cases that touch on the Commerce Clause.” ~Wikipedia Quote

The Twenty-First Amendment wording is:

Section 1. The eighteenth article of amendment to the Constitution of the United States is hereby repealed.

Section 2. The transportation or importation into any State, Territory, or possession of the United States for delivery or use therein of intoxicating liquors, in violation of the laws thereof, is hereby prohibited.

Section 3. This article shall be inoperative unless it shall have been ratified as an amendment to the Constitution by conventions in the several States, as provided in the Constitution, within seven years from the date of the submission hereof to the States by the Congress.

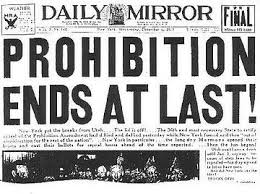

Prohibition lasted thirteen years before America came to its senses and legally regulated the production and distribution of properly-produced alcoholic beverages. The U.S. Constitution turned over all alcoholic regulation and enforcement to the state and local levels, where it should be, with the local demographic values setting the intoxicating substance standard.

Prohibition lasted thirteen years before America came to its senses and legally regulated the production and distribution of properly-produced alcoholic beverages. The U.S. Constitution turned over all alcoholic regulation and enforcement to the state and local levels, where it should be, with the local demographic values setting the intoxicating substance standard.

A lot of people prospered during Prohibition. A lot of people suffered during Prohibition. And the anti-alcohol social experiment colossally failed. But today, there’s no appreciable black market in the booze biz that legitimately generates a colossal tax base paid for by a fairly peaceable drinking crowd.

The War On Drugs

What did Albert Einstein say? Insanity is doing the same thing over and over and expecting different results? Boy, you’da think they learned. But, nope, by 1971 America had Richard Nixon and Tricky Dick need a cause to help keep his job. The war on drugs broke out.

“The war on drugs was a global campaign led by the U.S. federal government of drug prohibition, military aid, and military intervention, with the aim of reducing the illegal drug trade in the United States. The initiative includes a set of drug policies that are intended to discourage the production, distribution, and consumption of psychoactive drugs that the participating governments and the UN have made illegal. The term was popularized by the media shortly after a press conference given on June 18, 1971, by President Richard Nixon—the day after publication of a special message from President Nixon to the Congress on Drug Abuse Prevention and Control—during which he declared drug abuse “public enemy number one”.

That message to the Congress included text about devoting more federal resources to the “prevention of new addicts, and the rehabilitation of those who are addicted”, but that part did not receive the same public attention as the term “war on drugs”. However, two years prior to this, Nixon had formally declared a “war on drugs” that would be directed toward eradication, interdiction, and incarceration.[14] In 2015, the Drug Policy Alliance, which advocates for an end to the War on Drugs, estimated that the United States spends $51 billion annually on these initiatives, and in 2021, after 50 years of the drug war, others have estimated that the US has spent a cumulative $1 trillion on it.

On May 13, 2009, Gil Kerlikowske—the Director of the Office of National Drug Control Policy (ONDCP)—signaled that the Obama administration did not plan to significantly alter drug enforcement policy, but also that the administration would not use the term “War on Drugs”, because Kerlikowske considers the term to be “counter-productive”. ONDCP’s view is that “drug addiction is a disease that can be successfully prevented and treated… making drugs more available will make it harder to keep our communities healthy and safe”.

In June 2011, the Global Commission on Drug Policy released a critical report on the War on Drugs, declaring: “The global war on drugs has failed, with devastating consequences for individuals and societies around the world. Fifty years after the initiation of the UN Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs, and years after President Nixon launched the US government’s war on drugs, fundamental reforms in national and global drug control policies are urgently needed.” The report was criticized by organizations that oppose a general legalization of drugs.” ~Wikipedia Quote

“Drugs” is an all-encompassing term. You can successfully argue alcohol is a drug and it is. However, alcohol is a much more socially acceptable intoxicant than the evil ones like heroin, cocaine, PCP, methamphetamine and the deadly synthetic opioids like fentanyl. Marijuana is in a class of its own. In my three decades in the police and coroner service, I never saw anyone violent while high on weed, and I never found anyone dead from a THC overdose.

Illicit drugs have been floating around America for a long, long time. Indigenous folk used hallucinogenics like peyote and mescaline for religious insight and recreational fun. Morphine treated wounded soldiers in the Civil War, the Two World Wars, and Vietnam—some soldiers became severely addicted to this opium-based product.

Illicit drugs have been floating around America for a long, long time. Indigenous folk used hallucinogenics like peyote and mescaline for religious insight and recreational fun. Morphine treated wounded soldiers in the Civil War, the Two World Wars, and Vietnam—some soldiers became severely addicted to this opium-based product.

The 1890 Sears Roebuck catalog offered a gram of cocaine and a small syringe for a buck and a half. At that time, cocaine was still legal and it made Coca-Cola a light, refreshing drink. Marijuana? The hemp industry flourished in the south and was a clear and present danger to the cotton industry. Cannabis plants were outlawed, but not because of THC intoxication. It was purely a financial and political move to save the cotton plantations, blaming it on the slaves who needed to be protected from smoking the buds to kick back.

Successive U.S. presidencies bought into the war on drugs movement. Perhaps that was because it became too big to stop. Ford, Carter, Regan, Bush 41, Clinton, Bush 43, and Obama all threw massive money and military on the dope fire. Trump? Well, who knows what went on in that man’s mind. But it seems the new Oval Office manager is toning it right down when it comes to cracking down on crack.

Unlike the war on alcohol, which was fought on home turf, America took its war on drugs abroad. Foreign and domestic drug policy put enormous funds into eradication efforts in Mexico, Central America, and South America. Despite invading Panama to overthrow a drug-dealing dictator and chasing the cartels to the ends of the jungle, the drug flow into the United States never stopped.

At home, the jails filled with American citizens serving harsh time for non-violent, rather minor drug offenses. The southern border received a half-built wall that served no tactical purpose. And the inner-cities rang with gunshots, mostly aimed at visible minorities.

The 2011 Global Commission on Drug Policy report was right. The global war on drugs had failed, with devastating consequences for individuals and societies around the world. And a new approach, the National Prevention Strategy, set a framework towards preventing drug abuse and promoting healthy lives.

Why Did Alcohol Prohibition and The War On Drugs Colossally Fail?

Human nature. There’s something in human physiology and psychology that craves intoxicating substances. Always has been. Always will be.

There’s an insatiable demand from people who want to alter their state of consciousness. Call it getting drunk, high, stoned, or just a little buzzed. Where there’s a demand for a consumer product, there’ll always be a supplier.

There’s an insatiable demand from people who want to alter their state of consciousness. Call it getting drunk, high, stoned, or just a little buzzed. Where there’s a demand for a consumer product, there’ll always be a supplier.

Prohibiting alcohol and criminalizing drugs removed the supply chain from the safe and taxable regulation structure and fed it to the wild-west black market. Like the Tommygun gangsters of the Roaring Twenties, the AK47-toting cartels of today took the mean streets of America into their control and the American politicians facilitated it.

How to Solve the Substance Abuse Problem?

You can’t. You can only try to control it as much as possible. That’s by reducing the demand, especially of the hard-core toxins. Alcohol is a done deal. It’s the norm in North American society and here to stay for good. Cannabis is nearly there with only a few hold-outs on legalizing recreational THC.

I’m all for both, provided the alcohol and cannabis products are clean, safe, and dispensed so they’re not too easy for kids to get at.

Natural products like powdered cocaine (not crack) and heroin are candidates to be pharmaceutically released on a prescription-based system. I’m okay with that as the demand will move from the street to the stores and can work alongside controlled addiction recovery programs.

Synthetic opiates are a different story. Pain killers like fentanyl and its super-deadly sister carfentanil are extremely addictive and relatively easy to produce by the underworld. In concentrated form, and when mixed with other hard drugs, synthetic opiates are a scourge—a plague—causing unacceptable numbers of overdose deaths.

The only solution here is a free government-run dispensary and removing the profits from gangsters. It’s not going to be politically popular, but if societies want to get tough on drug-related crime, they have to make a change in the supply system and then slowly bring down the demand.

That leaves to a blended bag of others drug intoxicants. I can’t make a case for opening up the bottle containing LSD, crystal meth, speed, and ketamine. There’s no medical argument made for consuming these psychotic-causing poisons.

So there you have it. My conclusion—a tiered approach to controlling intoxicating substances is the most workable method of maximizing public health and minimizing criminal profits. Control the supply. Remove the criminal incentive. Clean it up and carefully release it while working long-term to curb the demand.

Remember what Einstein said. “Insanity is doing the same thing over and over and expecting different results.”

In the meantime, keep firing war-on-drugs bullets at the heads of low-life, black-market crack, meth, and street-grade fentanyl dealers.