The future is coming fast—especially in the film industry. Some of it’s already here. Augmented and virtual reality. CGIs. Digital recreation. Algorithmic editing. Edge computing. 5G/6G networks. Cloned voices. Scanned actors. Non-real celebrities. Drones. Artificially intelligent screenwriting. Remote filmmaking. 3D printed sets. 3D previsualization. Real-time rendering. Sound and light tech breakthroughs. DJI Ronin 4D 6K condensed cinematic lenses. Micro cameras. Avatars & holograms. Blockchain, crypto & NFTs. The Internet of Things (IoT). And, of course, the Metaverse.

The future is coming fast—especially in the film industry. Some of it’s already here. Augmented and virtual reality. CGIs. Digital recreation. Algorithmic editing. Edge computing. 5G/6G networks. Cloned voices. Scanned actors. Non-real celebrities. Drones. Artificially intelligent screenwriting. Remote filmmaking. 3D printed sets. 3D previsualization. Real-time rendering. Sound and light tech breakthroughs. DJI Ronin 4D 6K condensed cinematic lenses. Micro cameras. Avatars & holograms. Blockchain, crypto & NFTs. The Internet of Things (IoT). And, of course, the Metaverse.

The global film industry is huge. It’s astoundingly enormous, and it’s growing massively. According to a study by Globe Newswire, the worldwide film industry grew from $271.83 billion (US) in March 2021 to $325.06 billion in March 2022. That’s a compounded annual growth rate (CAGR) of 11.4% indicating in another four years, 2026, the film-making world will generate 479.63 billion dollars. By the end of this decade, it could be worth a trillion.

If you’re a regular DyingWords follower, you might’ve noticed I haven’t published a book in nearly two years. That’s because I’m immersed in the film industry—studying screenwriting, producing film content under my new company Twenty-Second Century Entertainment (22 ENT), and generally learning what this business is about. I’ve also done on-camera work as a crime and forensic resource in non-scripted documentaries that flowed from blog posts I’ve created. Plus, I’ve made some great filmmaking friends who are teaching this old dog new tricks.

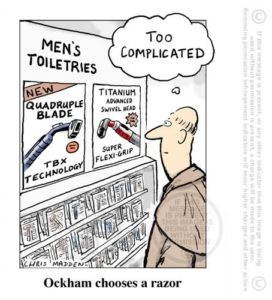

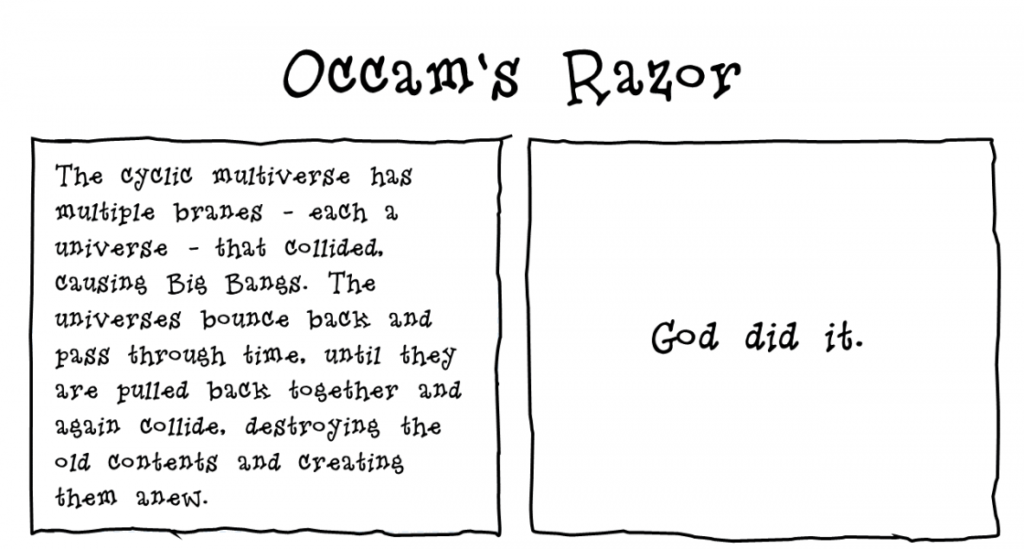

Before I expand on future film technology, I’ll give you a snapshot of what I’ve got on the go. My eight-part Based-On-True-Crime book series is contractually optioned by a producer who has it before a major film company. If this gets “Green Lit”, we have a total of thirty episodes loglined under the working title Occam’s Razor. My hardboiled, private detective storytelling concept called City Of Danger is a twenty-four-part series with a right-of-first-refusal agreement through a leading netstreamer. (See my webpage for City Of Danger—scheduled for 2024). The Fatal Shot is a film production “treatment” I wrote which is being “shopped around”, and I’m collaborating with a long-time colleague on a very interesting screen project titled Lightning Man that I believe has excellent film potential.

Enough of my BS. Let’s look at the futuristic film industry.

Everyone’s talking about the metaverse. Especially Mark Zuckerberg who rebranded Facebook into Meta. He’s betting big that this is Internet 3.0 and, from what I know, I’m sure he’s right even though he can’t get Apple to form a joint venture.

The term metaverse isn’t new. It’s been around three decades and was once known as cyberspace. Although the metaverse is already here and in its infancy or at an inflection point, it’s a hard concept to wrap your head around. Maybe it’s best to let Mr. Zuckerberg explain:

The term metaverse isn’t new. It’s been around three decades and was once known as cyberspace. Although the metaverse is already here and in its infancy or at an inflection point, it’s a hard concept to wrap your head around. Maybe it’s best to let Mr. Zuckerberg explain:

“The “metaverse” is a set of virtual spaces where you can create and explore with other people who aren’t in the same physical space as you. You’ll be able to hang out with friends, work, play, learn, shop, create and more. It’s not necessarily about spending more time online — it’s about making the time you do spend online more meaningful. The metaverse isn’t a single product one company can build alone. Just like the internet, the metaverse exists whether Facebook is there or not. And it won’t be built overnight. Many of these products will only be fully realized in the next 10-15 years. While that’s frustrating for those of us eager to dive right in, it gives us time to ask the difficult questions about how they should be built.”

Zuckerberg says the metaverse is the mobile web’s successor. First there was Internet 1.0 which was static. You could surf the pages and send emails on a desktop. Internet 2.0—where we’re at now—is mobile. It’s smartphone streaming and TikToking. If you want to call the metaverse Internet 3.0, then you need to use compatible words like immersive, interoperable, and integrated. It’s a world of shared virtual experience that can happen at home, on the go, and wherever you are with a connected device.

What the metaverse holds for the film industry is not so much technical advances in production. It’s deliverability and viewer experience. The metaverse won’t be the place you’ll be watching a movie. It’s where you’ll be fully interacting with your five senses—sight, sound, small, taste, and feel. It’ll be like you’re right there in the middle of the set.

If you’re interested in learning more about the metaverse, here are three resources I recommend:

The Metaverse: And How it Wil Revolutionize Everything —Book by Matthew Ball

Value Creation in the Metaverse — 76-page pdf by McKinsey & Company

What is the Metaverse? — Article at Government Technology

There are two evolving technologies that’ll give you that immersed feeling. One is augmented reality (AR). The other is virtual reality (VR). There’s a big difference between the two immersive platforms.

Augmented reality is enhancing, or augmenting, real events with computerization. AR morphs the mundane, physical world into a colorful, visual place by projecting visual images and characters into an existing framework. It adds to the user’s real-life experience.

Augmented reality is enhancing, or augmenting, real events with computerization. AR morphs the mundane, physical world into a colorful, visual place by projecting visual images and characters into an existing framework. It adds to the user’s real-life experience.

Virtual reality creates a world that doesn’t exist and makes it seem very, very real. Think the movie Avatar. VR also incorporates sensory-improving devices like goggles, helmets, headsets, and suits.

You could say computer-generated imagery, or CGIs, is old technology and not something futuristic. You’d be wrong. Advancements in CGI development are nothing short of breathtaking. The CGIs five years from now will make today’s stuff look like a preschooler’s drawing.

Technology’s ability to recreate faces, bodies, and even dialogue is dramatically improving. It’s progressing to the point where it’ll be possible to make an exact replica of just about anyone. Would you like to meet a completely believable Elvis Presley? How about Marilyn Monroe?

Speaking of Elvis and Marilyn, cloned voices are becoming the thing. Computerized synthetization takes old audio of past people and recreates their voices into a life-like state. This process will use artificial intelligence (AI) to build a smoky Marilyn or a crooning Elvis and respond to printed dialogue. It like the current AI text-to-speech but on steroids.

We can’t talk about futuristic filmmaking without bringing up artificial intelligence. AI is moving ahead at lightning speed and it’s bringing the film industry with it. I’m fascinated with AI developments. But I’m also a bit fearful. Here’s a DyingWords post I wrote a while back titled Helpful or Homicidal — How Dangerous is Artificial Intelligence (AI)?

We can’t talk about futuristic filmmaking without bringing up artificial intelligence. AI is moving ahead at lightning speed and it’s bringing the film industry with it. I’m fascinated with AI developments. But I’m also a bit fearful. Here’s a DyingWords post I wrote a while back titled Helpful or Homicidal — How Dangerous is Artificial Intelligence (AI)?

One thing about AI I’m really looking forward to in the film industry is this: Artificially Intelligent Screenwriting. If you’ve ever written, or have tried to write, a screenplay, then you appreciate how much work and effort goes into it, never mind the brain drain of creating unique content.

Recently, researchers at New York University built an artificial intelligence screenwriting program. They called it Benjamin who, among other things, wrote an original soundtrack for its movie after being programmed with 30,000 songs in its data input drive. Can you imagine the 2025 Academy Awards, “And the Oscars for best screenplay and soundtrack goes to… Benjamin the Bot.”

AI isn’t just real in script and score writing. Virtual actors and non-real celebrities are on the way in. It’ll soon be possible to select the movie cast and digitally scan them, then recreate their entire actions throughout the film without them being physically present. It’s well within the realm of possibility to have a virtual Ryan Reynolds or Anne Hathaway act their parts while the flesh and blood realities sit at home. After being paid a substantial sum for licensing their images, of course.

Turning real people into realistic avatars or digital images of themselves is a current technology. Take a look at the leading lady on my City Of Danger promo poster. That’s a real person (a stunningly attractive and stylish, high-status lady, by the way) who was scanned and run through a NextGen Pixlr filter. The plan for City Of Danger is to digitize the cast and set them loose in virtual reality following the human-written episodic scripts translated by AI. Fun stuff!

Drones are fun stuff, too. What used to be aerial filmed with helicopters and airplanes is now drone territory. Drones are far cheaper and much safer. With highly sophisticated controls and cameras, filming by drones will mostly replace piloted vehicles. Take a look at this drone footage of the new Vancouver Island Film Studios, twenty minutes north of my place: https://youtu.be/aTsyRrROx34

Remote filmmaking will put a big dent into on-site producing. With huge advances in film technology, internet sharing, and cost-cutting, more and more productions will happen on sound stages like the six built at Vancouver Island Film Studios. It’s realistic that a director—yes, a real person—will do their work remotely. Instead of fighting traffic and flight delays, a filmmaker will be able to do their job sitting on a yacht in the Maldives and direct their work in the metaverse.

3D printed sets are soon to be here, if not right now. It’s going to be far more efficient to create film set artifacts rather than source them. Those 3D objects can also be scanned and set into virtual reality situations.

3D filming has come a long way since the days audiences sat watching The Power Of Love back in 1922 and wearing those goofy glasses. Now, we have up-close 3D on the laptops and soon to be glasses-free for the big screen. But the big wait for is 4D filming, and it’s a promise to come through VR in the metaverse. Instead of only seeing height, width, and length, you’ll experience depth. You’ll be inside the picture—on the inside looking out at the 3D world.

There are massive changes coming in cameras, sound recording, and lighting effects. Have you seen Top Gun Maverick? That is amazing work, and that’s just the next step in futuristic filmmaking. And you know what? Very little was done through CGIs. It’s just super sophisticated camera, sound, and lighting effects. Here’s how they did it: https://www.indiewire.com/2022/06/top-gun-maverick-making-of-cockpit-1234729694/

There are massive changes coming in cameras, sound recording, and lighting effects. Have you seen Top Gun Maverick? That is amazing work, and that’s just the next step in futuristic filmmaking. And you know what? Very little was done through CGIs. It’s just super sophisticated camera, sound, and lighting effects. Here’s how they did it: https://www.indiewire.com/2022/06/top-gun-maverick-making-of-cockpit-1234729694/

Top Gun Maverick used a Sony Rialto Camera Extension System. Yes, it’s expensive but so were renting the jets at over $11,000 per flying hour. More reasonable in my upcoming league is the no-longer-futuristic DJI Ronin 4D $-Axis 6K Cinematic Camera that recently came online at $9,000.00, and that’s just for the lens. Think about it—a 4D, 6,000-pixel digital camera. There isn’t a 6K monitor yet made, but I bet it’s on its way.

Micro cameras have amazing potential. The future is wide open in melding nanotechnology with filmmaking. I can’t imagine what’s happening at the molecular level.

I can imagine, however, what’s happening in the post-production level. It’s not just screenwriting, casting, set building, and cinematography that takes time and money. Editing is a huge time suck in the filmmaking process. What’s just arriving is algorithmic film editing. This is AI software that thinks through the film data and makes automatic jump cuts at precisely the right moment.

Have you heard of edge computing? I hadn’t until I began investigating the futuristic film industry. Edge computing is capturing data at its source and not having to upload it to a server for processing. That eliminates having to use an expensive and laggy “middle-man” like a cloud or a mechanical server. Using edge computing to harness and develop digital data speeds up processing time and reduces costs.

Hologram displays are in their crude evolutionary form today. That’s going to change soon, and holograms are part of the new, end-product “dimensional delivery”. By dimensional delivery, I mean the 4D technology where you’ll be able to watch a digitized hologram of your show. It will be like watching a completely realistic stage play, and you’ll have the option of joining in.

“Joining in” is a fascinating film delivery concept. In the future, algorithms will track your viewing habits/choices and will give you the option of personalizing your selection. You can make yourself into an avatar and can substitute your avatar for a cast member. On the international stage, you can change your race, gender, and language.

All this talk of high-density technology needs delivery infrastructure makeover. Internet providers today don’t have the speed or capacity to process and send out 5K resolution and totally digitized, virtual reality entertainment. But that’s changing, too, with 5G.

5G is the 5th generation wireless mobile network. It’s already happening and 6G is planned. To serve the metaverse, massively higher, multi-Gbps and ultra-low latency is crucial. The 5 and 6G networks will deliver the films of the future that today’s 4G system can’t.

One more film-world reality is money. Movies cost a lot of money to make. I’m told a show like Occam’s Razor typically budgets at around $50,000 per edited minute of film. Doing the math, a 60-minute episode would cost $3 million, give or take a fudge factor. So, a 10-episode season would cost the film’s financier around $30 million. To me, that’s a lot of coin—a lot of coin that can be saved through emerging technology.

Future technology will significantly reduce time and expenses in film making. Payment methods are changing, too. Blockchain will keep a digital trail and funds will commonly exchange in crypto currency. Non Fungible Tokens (NFTs) will probably be part of the package, though they’re going through a reevaluation at the moment.

Future technology will significantly reduce time and expenses in film making. Payment methods are changing, too. Blockchain will keep a digital trail and funds will commonly exchange in crypto currency. Non Fungible Tokens (NFTs) will probably be part of the package, though they’re going through a reevaluation at the moment.

I’m a newbie to the film industry, but everyone working in the business is a newbie to what’s coming at us from the future. My niche is making content—inventing and telling stories through characters, plots, and dialogues. But to make decent (meaning saleable) content, I must be aware of how the overall film production and delivery systems work. That’s what the past two years have been about.

City Of Danger seems to be saleable content. At least one film producer at a name-brand netstreamer thinks so. Realistically, the show is a few years away—2024 at the earliest—because the technology for what we want to portray isn’t perfected yet. Our plan is to screenwrite the 24 episodes (underway) and have it ready to be digitally produced in virtual reality by scanning the actors, turning them into avatars, and showing them as you see Susan Silverii who graces the promo poster. This should cut production costs to maybe half of today’s typical rates of filming a live actor and on-location series like Occam’s Razor.

Wish us luck. Or, as they say in theatrics, “Break a leg”.