Last month another police officer took his own life after a lengthy battle with Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. I’ve handled lots of suicide cases over the years, but this one hit close to home – I knew Corporal Ken Barker. We’d worked together prior to the events which brought on Ken’s PTSD.

Last month another police officer took his own life after a lengthy battle with Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. I’ve handled lots of suicide cases over the years, but this one hit close to home – I knew Corporal Ken Barker. We’d worked together prior to the events which brought on Ken’s PTSD.

Ken was one of the best-liked, most approachable Royal Canadian Mounted Police members I ever met. He certainly wasn’t the stereotype who’d you think would suffer a PTSD mental illness. Wait – there’s no such thing as a stereotype PTSD sufferer and, yes, PTSD is a mental illness.

There’s a higher awareness of PTSD today than back in the 1990’s when I was posted with Ken. Personally, I’ve experienced events as a cop and a coroner which should have brought on PTSD in me, but didn’t. I was very aware of the disorder and knew to recognize the signs. Also, I wasn’t scared to talk about PTSD and I think that’s the best form of prevention and treatment.

There’s a higher awareness of PTSD today than back in the 1990’s when I was posted with Ken. Personally, I’ve experienced events as a cop and a coroner which should have brought on PTSD in me, but didn’t. I was very aware of the disorder and knew to recognize the signs. Also, I wasn’t scared to talk about PTSD and I think that’s the best form of prevention and treatment.

Today, I watch with caution as my son’s career in the Canadian Army unfolds and the suicide deaths of soldiers pile up into a national crisis. There are more Canadian soldiers who died of PTSD related suicides than were killed in ten years of active combat in Afghanistan.

So who is this Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder bitch?

Clinically, PTSD is classified as a trauma and stress related disorder stipulated in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders IV.

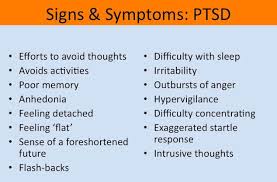

It’s simply summarized as:

1. Exposure to a traumatic event.

This includes both physical harm, or the risk of serious injury or death to self or others, and a response to the event that involved intense fear, horror, or helplessness. The traumatic event should be of a type that would cause significant symptoms of distress in almost anyone, and that the event was outside the range of usual human experience.

2. Persistent re-experiencing.

One or more of these must be present in the victim: flashback memories, recurring distressing dreams, subjective re-experiencing of the traumatic event(s), or intense negative psychological or physiological response to any reminder of the traumatic event(s).

One or more of these must be present in the victim: flashback memories, recurring distressing dreams, subjective re-experiencing of the traumatic event(s), or intense negative psychological or physiological response to any reminder of the traumatic event(s).

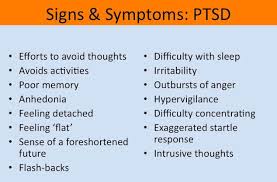

A. Persistent avoidance and emotional numbing.

This involves a sufficient level of avoidance of stimuli associated with the trauma, such as certain thoughts or feelings, or talking about the event(s) and avoidance of behaviours, places, or people that might lead to distressing memories as well as the disturbing memories, dreams, flashbacks, and intense psychological or physiological distress. It includes the inability to recall major parts of the trauma(s), or decreased involvement in significant life activities as well as a decreased capacity (down to complete inability) to feel certain feelings, and an expectation that one’s future will be somehow constrained in ways not normal to other people.

This involves a sufficient level of avoidance of stimuli associated with the trauma, such as certain thoughts or feelings, or talking about the event(s) and avoidance of behaviours, places, or people that might lead to distressing memories as well as the disturbing memories, dreams, flashbacks, and intense psychological or physiological distress. It includes the inability to recall major parts of the trauma(s), or decreased involvement in significant life activities as well as a decreased capacity (down to complete inability) to feel certain feelings, and an expectation that one’s future will be somehow constrained in ways not normal to other people.

B. Persistent symptoms of increased arousal not present before.

These are all physiological response issues, such as difficulty falling or staying asleep, or problems with anger, concentration, or hyper-vigilance. Additional symptoms include irritability, angry outbursts, increased startle response, and concentration or sleep problems.

C. Duration of symptoms for more than 1 month.

If all other criteria are present but 30 days have not elapsed, the individual is diagnosed with acute stress disorder. Anything longer would be considered chronic.

D. Significant impairment.

The symptoms reported must lead to clinically significant distress or impairment of major domains of life activity, such as social relations, occupational activities, or other important areas of functioning.

Although most people with PTSD will develop symptoms within three months of the traumatic event, some people don’t notice any symptoms until years after. A major increase in stress, or exposure to a reminder of the trauma, can trigger symptoms to appear months or years later.

Although most people with PTSD will develop symptoms within three months of the traumatic event, some people don’t notice any symptoms until years after. A major increase in stress, or exposure to a reminder of the trauma, can trigger symptoms to appear months or years later.

Who’s susceptible to PTSD?

Generally, at highest risk are those who experience traumatic events more frequently and for longer exposure. Combat personnel (soldiers, sailors, and airmen) are at the forefront, followed by emergency responders like police, firefighters, and medical professionals.

There are other risk groups. Survivors of violent acts like sexual assault and attempted murder commonly experience post-traumatic stress. This extends to accident victims and witnesses of violent incidents.

There are other risk groups. Survivors of violent acts like sexual assault and attempted murder commonly experience post-traumatic stress. This extends to accident victims and witnesses of violent incidents.

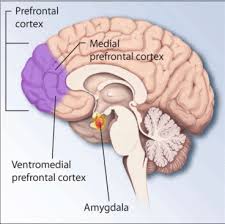

What’s the medical reason for PTSD?

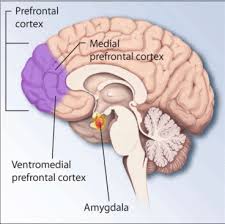

Three areas of the brain which control and administer PTSD have been identified. They’re the prefrontal cortex, the amygdala, and the medial prefrontal cortex.

Traumatic events cause an over-reactive adrenaline response, which creates deep neurological patterns in the brain.

These patterns can persist long after the event that triggered the fear, making an individual hyper-responsive to future fearful situations. During traumatic experiences, the high levels of stress hormones secreted suppressed hypothalamic activity that may be a major factor toward the development of PTSD.

These patterns can persist long after the event that triggered the fear, making an individual hyper-responsive to future fearful situations. During traumatic experiences, the high levels of stress hormones secreted suppressed hypothalamic activity that may be a major factor toward the development of PTSD.

These biochemical changes in the brain and body differ from other psychiatric disorders such as major depression and bi-polar. Individuals diagnosed with PTSD respond more strongly to a dexamethasone suppression test than individuals diagnosed with clinical depressions.

In addition, most people with PTSD also show a low secretion of cortisol and high secretion of catecholamines in urine with a norepinephrine / cortisol ratio consequently higher than comparable non-diagnosed individuals. This contrasts to the normal fight-or-flight response, in which both catecholamine and cortisol levels are elevated after exposure to stress.

In addition, most people with PTSD also show a low secretion of cortisol and high secretion of catecholamines in urine with a norepinephrine / cortisol ratio consequently higher than comparable non-diagnosed individuals. This contrasts to the normal fight-or-flight response, in which both catecholamine and cortisol levels are elevated after exposure to stress.

Getting clinical – brain catecholamine levels are high and corticotropin concentrations are high. Together, these create an abnormality in the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis.

The HPA axis is responsible for coordinating the hormonal response to stress. Given the strong cortisol suppression to dexamethasone in PTSD, HPA axis abnormalities are predicated on strong negative feedback inhibition of cortisol, itself likely due to an increased sensitivity of glucocorticoid receptors.

Translating this reaction to human conditions gives a patho-physiological explanation for PTSD by a maladaptive learning pathway to fear response through a hyper-sensitive, hyper-reactive, and hyper-responsive HPA axis.

Low cortisol levels may also predispose individuals to PTSD and studies indicate that people that suffer from PTSD have chronically low levels of serotonin, which contributes to the commonly associated behavioral symptoms such as anxiety, ruminations, irritability, aggression, suicidality, and impulsivity. Serotonin also contributes to the stabilization of glucocorticoid production.

Low cortisol levels may also predispose individuals to PTSD and studies indicate that people that suffer from PTSD have chronically low levels of serotonin, which contributes to the commonly associated behavioral symptoms such as anxiety, ruminations, irritability, aggression, suicidality, and impulsivity. Serotonin also contributes to the stabilization of glucocorticoid production.

Insufficient dopamine levels in patients with PTSD can contribute to anhedonia, apathy, impaired attention and moto-skill defects. Increased levels of dopamine leads to psychosis, agitation, and restlessness.

Why are flashbacks so common in PTSD sufferers?

In a traumatic experience, the mind processes and stores the memory differently than it stores regular experiences.

Sensory information about the trauma – smells, sights, sounds, tastes, and the feel of things – is given high priority in the mind and is remembered as something threatening.

Once this happens, whenever the sufferer is faced with a touch, a taste, a smell, a feel, or a sight that reminds them of the trauma, the memory (and the feeling of threat) comes back up and vivid memories or flashbacks about the trauma occur.

Once this happens, whenever the sufferer is faced with a touch, a taste, a smell, a feel, or a sight that reminds them of the trauma, the memory (and the feeling of threat) comes back up and vivid memories or flashbacks about the trauma occur.

Getting all clinical again, a hyper-responsiveness in norepinephrine receptors in the prefrontal cortex is connected to the flashbacks. A decrease in other norepinephrine functions prevents the memory mechanisms in the brain from processing that the experience and emotions the person is experiencing during a flashback are not associated with the current environment. In other words, it takes them right back to the trauma time and it seems very, very real.

What can be done about it?

Many sufferers feel guilt or shame around PTSD because they’re often told they should just ‘suck-it-up’ to get over difficult experiences. Others feel embarrassed in talking with others. Some feel like it’s somehow their own fault.

Here’s the common treatments.

Counselling

Cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT) is effective. Very effective. CBT teaches how thoughts, feelings, and behaviours work together and how to deal with problems and stress. Relaxation techniques, such as meditation and hypnosis are used. This exposure therapy helps the sufferer talk about their experience and helps reduce avoidance.

Cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT) is effective. Very effective. CBT teaches how thoughts, feelings, and behaviours work together and how to deal with problems and stress. Relaxation techniques, such as meditation and hypnosis are used. This exposure therapy helps the sufferer talk about their experience and helps reduce avoidance.

In my experience, this stuff works. But the sufferer has to know the disorder before accepting the treatment.

Medication

A number of medications can prevent PTSD or reducing its incidence, especially when given in close proximity to a traumatic event. These include:

SSRIs (Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors)

SSRIs are considered to be a first-line drug treatment. They include citalopram, escitalopram, fluoxetine, paroxetine, and sertraline.

Tricyclic antidepressants

Amitriptyline benefits distress and avoidance symptoms. Imipramine is effective for intrusive symptoms.

Alpha-adrenergic antagonists

In a study of combat veterans, prazosin shows substantial benefit in relieving or reducing nightmares. Clonidine helps with startle, hyper-arousal, and general autonomic hyper-excitability.

Anti-convulsants, mood stabilizers, and anti-aggression agents

Carbamazepine reduces arousal symptoms involving noxious affect, as well as mood or aggression factors. Topiramate is effective in achieving major reductions in flashbacks and nightmares. Zolpidem proves useful in treating sleep disturbances. Lamotrigine reduces re-experiencing symptoms as well as avoidance and emotional numbing. Valproic acid reduces symptoms of irritability, aggression, impulsiveness, and reducing flashbacks. Similarly, lithium carbide works well to control mood and aggressions (but not anxiety) symptoms. Buspirone has an effect similar to lithium, with the additional benefit of reducing hyper-arousal symptoms.

Carbamazepine reduces arousal symptoms involving noxious affect, as well as mood or aggression factors. Topiramate is effective in achieving major reductions in flashbacks and nightmares. Zolpidem proves useful in treating sleep disturbances. Lamotrigine reduces re-experiencing symptoms as well as avoidance and emotional numbing. Valproic acid reduces symptoms of irritability, aggression, impulsiveness, and reducing flashbacks. Similarly, lithium carbide works well to control mood and aggressions (but not anxiety) symptoms. Buspirone has an effect similar to lithium, with the additional benefit of reducing hyper-arousal symptoms.

Antipsychotics

Risperidone is the main medication for dissociation, mood issues, and aggression issues while cyproheptadine, a serotonin antagonist, helps with sleep disorders and nightmares.

Atypical antidepressants

Nefazodone works with sleep disturbance symptoms, secondary depression, anxiety, and sexual dysfunction symptoms. Trazodone reduces or eliminates problems with anger, anxiety, and disturbed sleep.

Beta Blockers

Propranolol has demonstrated possibilities in reducing hyper-arousal symptoms, including sleep disturbances – but the jury’s out.

Benzodiazepines

These drugs are not recommended by clinical guidelines for the treatment of PTSD due to a lack of evidence of benefit. Nevertheless, some doctors use benzodiazepines with caution for short-term anxiety relief of hyper-arousal and sleep disturbance, and believe that the use of benzodiazepines is proper for acute stress, as this group of drugs promotes dissociation and ulterior revivals. While benzodiazepines can alleviate acute anxiety, there is no consistent evidence that they can stop the development of PTSD, or are at all effective in the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder.

These drugs are not recommended by clinical guidelines for the treatment of PTSD due to a lack of evidence of benefit. Nevertheless, some doctors use benzodiazepines with caution for short-term anxiety relief of hyper-arousal and sleep disturbance, and believe that the use of benzodiazepines is proper for acute stress, as this group of drugs promotes dissociation and ulterior revivals. While benzodiazepines can alleviate acute anxiety, there is no consistent evidence that they can stop the development of PTSD, or are at all effective in the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder.

Additionally, benzodiazepines may reduce the effectiveness of psychotherapeutic interventions, and there’s some evidence that benzodiazepines contribute to the development and chronification of PTSD. Other drawbacks include the risk of developing a benzodiazepine dependence and withdrawal syndrome. Additionally, individuals with PTSD are at an increased risk of abusing benzodiazepines.

Glucocorticoids

High-dose corticosterone administration was recently found to reduce ‘PTSD-like’ behaviours in a rat models. In this study, corticosterone impaired memory performance, suggesting that it may reduce risk for PTSD by interfering with consolidation of traumatic memories. The neurodegenerative effects of the glucocorticoids, however, may prove this treatment counterproductive.

That’s great lab-rat stuff which I’m not going to try myself. However, the next stuff is something that I think ‘where’s there’s smoke – there’s fire”.

Cannabis

There’s a study underway between a University and one of Canada’s largest producers of medicinal cannabis, suggesting that the active ingredients in marihuana – tetrahydrocannabinol and cannabinoids – may be very effective in reducing PTSD symptoms. Many PTSD sufferers self-medicate through black-market cannabis and swear by it. It’ll be interesting to see this clinical study’s results.

There’s a study underway between a University and one of Canada’s largest producers of medicinal cannabis, suggesting that the active ingredients in marihuana – tetrahydrocannabinol and cannabinoids – may be very effective in reducing PTSD symptoms. Many PTSD sufferers self-medicate through black-market cannabis and swear by it. It’ll be interesting to see this clinical study’s results.

Support groups

Support groups definitely help. Here people share experiences and learn from others. Connecting with people who understand what the sufferer goes through is probably the most effective form of treatment and this leads to identifying other forms of treatment such as medication and psychological intervention.

Support groups definitely help. Here people share experiences and learn from others. Connecting with people who understand what the sufferer goes through is probably the most effective form of treatment and this leads to identifying other forms of treatment such as medication and psychological intervention.

PTSD awareness is much greater in the twenty-first century, but the disorder is long known and buried. Historically they called it battle fatigue, shell-shock, and the thousand-yard stare. Soldiers were actually shot by their own command for perceived cowardness. I’ll bet the majority weren’t afraid – they were just suffering a nasty bitch of a disorder.

On a personal note – looking back – I believe my dad suffered from PTSD. He was a gunner on a RCAF Lancaster bomber during World War II; the veteran of 113 operational runs. If that doesn’t do something to the psyche, I don’t know what would. I remember him sitting for long periods… on a big flat rock in our yard… in that thousand-yard stare… until his cigarette… burned down to his fingers… and snapped him back to reality.

On a personal note – looking back – I believe my dad suffered from PTSD. He was a gunner on a RCAF Lancaster bomber during World War II; the veteran of 113 operational runs. If that doesn’t do something to the psyche, I don’t know what would. I remember him sitting for long periods… on a big flat rock in our yard… in that thousand-yard stare… until his cigarette… burned down to his fingers… and snapped him back to reality.

After nearly six decades of life experience and being exposed to more traumatic life & death exposures than I can count, I can’t say that I’ve experienced PTSD.

Grief, yes. Compassion; in spades. Fear – I’ve been absolutely shit-scared, bewildered, and abhorred; being down on my belly under gunfire and questioning the existence and authority of Infinite Intelligence. But I’ve never experienced guilt and I don’t know much about it. Guilt seems like an evil, degenitive force who’s metaphysical purpose is to destruct. A lot more needs to be known about the psychological effects of guilt.

I think guilt is the nasty bitch in PTSD and I think that guilt walks hand-in-hand with shame.

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder is a complex mix of psychological, physiological, and metaphysical workings and it’s nothing to be guilty about or ashamed of. It’s a naturally-occurring, mental illness. With proper support and effective treatment, PTSD sufferers can fully recover.

Remember, PTSD isn’t about what’s wrong. It’s about what’s happened.

Please leave your comments, ask questions, or tell about your experiences. It’s okay to talk about PTSD and raising awareness is the best form of treatment… and prevention.

Catastrophe planning in the civilian world is primarily the province of engineers and management. The problem with that is engineers and management are trained for, plan for, and work in a controlled environment (what they think is a controlled environment). So delusion events are outside their comfort zone; aberrations.

Catastrophe planning in the civilian world is primarily the province of engineers and management. The problem with that is engineers and management are trained for, plan for, and work in a controlled environment (what they think is a controlled environment). So delusion events are outside their comfort zone; aberrations.  West Point is an extraordinarily controlled environment. Things run almost perfectly there; so much so that graduates often have problems adjusting to the ‘real’ Army they go into. But West Point also has over 200 years of experience training leaders and preparing soldiers for war. This accumulation of institutional knowledge is inculcated in cadets in a high-pressure cauldron of mental, physical, and emotional stress for four years.

West Point is an extraordinarily controlled environment. Things run almost perfectly there; so much so that graduates often have problems adjusting to the ‘real’ Army they go into. But West Point also has over 200 years of experience training leaders and preparing soldiers for war. This accumulation of institutional knowledge is inculcated in cadets in a high-pressure cauldron of mental, physical, and emotional stress for four years. Special Operations soldiers train for war. War is called controlled chaos; an incessant series of cascade events. War might be considered the ultimate catastrophe and combat a final event. In order to prepare for this final event, Special Operations soldiers train for, plan for, and work in a chaotic environment every day.

Special Operations soldiers train for war. War is called controlled chaos; an incessant series of cascade events. War might be considered the ultimate catastrophe and combat a final event. In order to prepare for this final event, Special Operations soldiers train for, plan for, and work in a chaotic environment every day. The basic problem and the opening of the movie was set up this way: A Star Fleet ship which the student commands is patrolling near the neutral zone. A distress call is received from a disabled Federation vessel inside the neutral zone. An enemy warship is approaching from the other side. It’s a vessel more powerful than the one the student commands. The choices seem obvious: ignore the distress call (which violates the law of space) or go to its aid (violating the neutral zone) and face almost certain destruction from the enemy vessel. As you can see, both choices are bad.

The basic problem and the opening of the movie was set up this way: A Star Fleet ship which the student commands is patrolling near the neutral zone. A distress call is received from a disabled Federation vessel inside the neutral zone. An enemy warship is approaching from the other side. It’s a vessel more powerful than the one the student commands. The choices seem obvious: ignore the distress call (which violates the law of space) or go to its aid (violating the neutral zone) and face almost certain destruction from the enemy vessel. As you can see, both choices are bad. What Kirk did was sneak into the computer center the night before he was scheduled to go through the simulation and change the parameters so that he could successfully save the vessel without getting destroyed. Would you have thought of that? Was it cheating? If you ain’t cheating you ain’t trying. It’s not cheating when it succeeds.

What Kirk did was sneak into the computer center the night before he was scheduled to go through the simulation and change the parameters so that he could successfully save the vessel without getting destroyed. Would you have thought of that? Was it cheating? If you ain’t cheating you ain’t trying. It’s not cheating when it succeeds. A doctor? Lawyer? Engineer? MBA? Teacher? While they all have special skills, I submit that the overwhelming choice might well be a US Special Forces Green Beret or, the best in the business – a British 22SAS. Someone trained in survival, medicine, weapons, tactics, communications, engineering, counter-terrorism, tactical and strategic intelligence, and with the capability to be a force multiplier.

A doctor? Lawyer? Engineer? MBA? Teacher? While they all have special skills, I submit that the overwhelming choice might well be a US Special Forces Green Beret or, the best in the business – a British 22SAS. Someone trained in survival, medicine, weapons, tactics, communications, engineering, counter-terrorism, tactical and strategic intelligence, and with the capability to be a force multiplier. Often, in order to deal with a cascade event, leadership and courage are needed to go against a culture of complacency and fear. In every catastrophe, fear is a factor in at least one, if not more, cascade events. This fear runs the gamut from physical fear, to job security fear, to social fear, to physical fear. Few people want to be the ‘boy who cries wolf’ even when they see a pack of wolves. What’s even harder is when we’re the only one who sees the wolf in sheep’s clothing.

Often, in order to deal with a cascade event, leadership and courage are needed to go against a culture of complacency and fear. In every catastrophe, fear is a factor in at least one, if not more, cascade events. This fear runs the gamut from physical fear, to job security fear, to social fear, to physical fear. Few people want to be the ‘boy who cries wolf’ even when they see a pack of wolves. What’s even harder is when we’re the only one who sees the wolf in sheep’s clothing. I’ve written Shit Doesn’t Just Happen: The Gift of Failure to help individuals and organizations avoid catastrophes, but I come at it from a different direction as a former Special Operations soldier. In the Special Forces (Green Berets) the key to our successful missions was the planning. The preparation. In isolation, we war-gamed as many possible catastrophe situations we could imagine for any upcoming mission and prepared as well as we could for them. In fact, we expected things to go wrong, a very different mindset from that of engineers and management.

I’ve written Shit Doesn’t Just Happen: The Gift of Failure to help individuals and organizations avoid catastrophes, but I come at it from a different direction as a former Special Operations soldier. In the Special Forces (Green Berets) the key to our successful missions was the planning. The preparation. In isolation, we war-gamed as many possible catastrophe situations we could imagine for any upcoming mission and prepared as well as we could for them. In fact, we expected things to go wrong, a very different mindset from that of engineers and management.